The slipper lobster, locally known in the Philippines as pitik-pitik, may not be as famous as their cousins, the spiny lobsters or banagan, nor the “true” clawed lobsters of the North Atlantic. They are, however, a fraction of the price, costing only Ph 500 to Ph 700 ($9.45 to $13.23) per kilogram in the Philippines compared to Ph 1,500 to Ph 6,000 ($28.35 to $113.42) for a kilogram live catch of spiny lobster. In short, the slipper lobster is a delicious bargain.

Slipper lobster, one of the lobster species traded in the Phillipines that is now the subject of studies at SEAFDEC/AQD in Tigbauan, Iloilo © JF Aldon

Tasting somewhere between a clawed lobster and shrimp, the slipper lobster (Thenus orientalis) offers a good value on the seafood menu and is a sought-after local delicacy. It also holds a good potential of being sustainably farmed.

Currently, lobsters are mainly captured in traps or hand-caught by divers. Unfortunately, due to their high value, indiscriminate gathering occurred, particularly among spiny lobsters (Panulirus spp), prompting the Department of Agriculture to establish collection and trade restrictions in 2020.

Expansion of the lobster industry is thus set on farming the commodity. However, the absence of viable hatcheries to produce lobster seed poses a major roadblock to a lobster bonanza. At present, lobster farms still rely on fishers supplying them with wild-sourced juveniles under the eye of regulators.

Breeding and producing domesticated spiny lobsters have been actively pursued for decades, but they grow slowly, and their larval development is complicated, making the pursuit technically challenging. This is where the more affordable slipper lobster captures the hopes of sea farmers and aquaculture researchers.

While spiny lobsters take their time with larval development, taking up to 300 days, the slipper lobster larvae are reared within 30 days. Likewise, the spiny lobster goes through up to 11 larval development stages, while the slipper lobster only has four.

Seeing the tremendous potential in slipper lobster production, researchers at the Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Centre Aquaculture Department (SEAFDEC/AQD) embarked on the task of developing hatchery techniques in the Philippines as one of the prime candidate species, Thenus orientalis.

According to Dr Shelah Mae Ursua, the project leader at SEAFDEC/AQD, they chose to study the slipper lobster not just because of its shorter larval stages but because its larvae are also hardier than the spiny lobster.

Also, to its credit, slipper lobster’s culture period from hatching to reaching market size is 14 to 16 months, trumping the 22 to 24-month period for the spiny lobster.

First successes

To breed the lobsters, Dr Ursua arranged in April 2021 for specimens to be transported from Negros Island to SEAFDEC/AQD’s experimental facilities in Tigbauan, Iloilo, an eight-hour journey by land and sea.

Video capture of an egg-bearing slipper lobster releasing its hatchlings at the SEAFDEC/AQD hatchery in Tigbauan, Iloilo © SEAFDEC/AQD

By September 2021, egg-bearing lobsters started to hatch their brood. In October of the same year, another milestone was achieved ̶ a slipper lobster fanned out thousands of eggs with its pleopods to facilitate the hatching of phyllosoma larvae in full view of video cameras, vividly documenting its hatching behaviour.

“With the recent spawning and hatching of the slipper lobster, we expect to successfully breed the slipper lobster in the laboratory. Right now, we are in the first stage of completing the life cycle in captivity,” said Dr Leobert de la Peña, the Research Division Head at SEAFDEC/AQD.

Future direction

Slipper lobsters continue to hatch at Dr Ursua’s laboratory. Her team is currently working to study the best way to grow the phyllosoma larvae, maintaining the water quality and feeding them the proper food before they are grown in nurseries and grow-out cages.

“The larval rearing stage is the most challenging phase of its life cycle development. Upon successfully rearing the phyllosoma larvae, the hatchery-produced seeds will be used for the experimental run in the grow-out culture of the slipper lobsters,” de la Peña added.

SEAFDEC/AQD Chief Dan Baliao commended Dr Ursua’s project for the strides they have achieved only two years since the slipper lobster project launched with funding support from the Government of Japan Trust Fund (GOJ-TF). The project is programmed to continue until 2024.

“With the recent spawning and hatching of the slipper lobster, we could already standardise the protocols in the hatchery stage of the slipper lobster,” Baliao added.

For Dr Sayaka Ito, SEAFDEC/AQD Deputy Chief, the research on this commodity is also important to promote the slipper lobster as a new local aquaculture industry and open more livelihood opportunities.

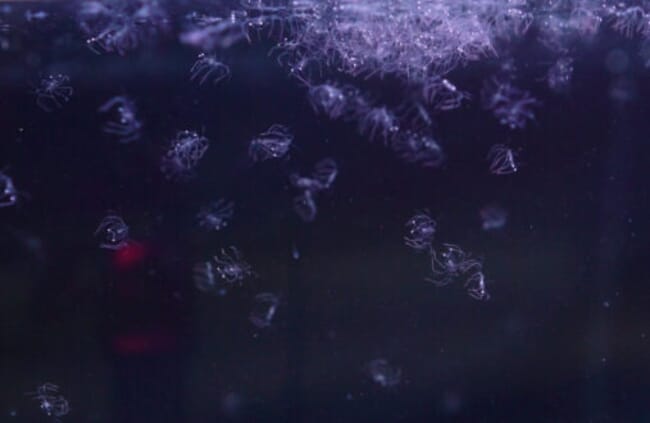

Video capture of a mass of phyllosoma larvae floating to the surface after hatching from an egg-bearing slipper lobster © SEAFDEC/AQD

So far, the most successful lobster farming industry is in Vietnam, where an estimated 1,600 tonnes of spiny lobsters, worth $120 million, were reportedly farmed in 2016.

“Although lobster aquaculture production, which depends on natural seedlings, is unstable, it is a significant livelihood source for some coastal communities in Indonesia and Vietnam,” said Baliao. “If we succeed in mass production of the seedlings, we can sustainably supply those many times over, and it will contribute greatly to the stable production of the lobster.”