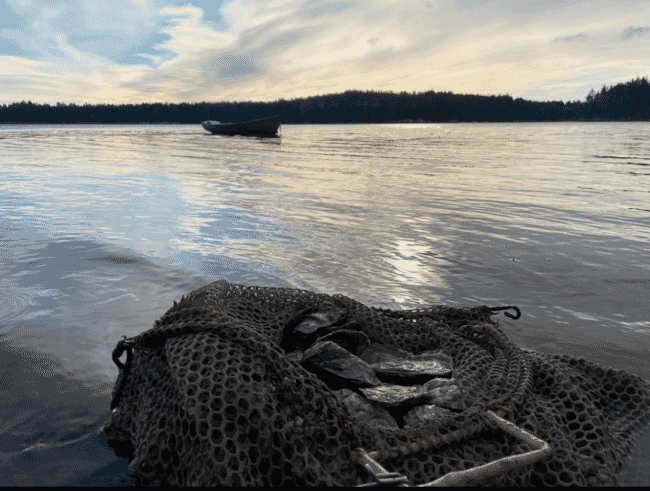

Barrows is working to reduce the amount of plastic used in oyster farming

Briefly describe your aquaculture career

I studied for a BSc in marine biology at the University of Tasmania in 2007. After graduating, I worked internationally for a year, focusing on marine biology projects like survey work with seahorses in Papua New Guinea. Eventually, I found myself back in my hometown and then worked abroad on and off for years.

I had the opportunity of a trip to Antarctica, where I did a ground-breaking study last year, looking at air samples for microplastics. Just a couple of months ago, I spent three weeks in Indonesia on a riverboat collecting water and air samples to look for microplastic contamination in Raja Ampat, one of the richest marine biodiversity areas in the world. I am currently in the process of finishing the analysis of those samples, while also managing my oyster business.

What inspired you to embark on a career in oyster aquaculture?

In 2015 I called a woman I had been working with and asked her if I could have some oysters. She replied that she didn't have any oysters but asked if I wanted to buy the oyster farm. In eight months, I was the owner of Long Cove Sea Farm, and from then onwards, I learnt as I went along and built it into a commercial business.

Barrows is raising oysters across three acres of coastal land

Slowly, I built more oyster gear and got a larger boat and at that same time, I was running a microplastics research lab on the island and processing international samples.

I had these two different careers and wanted them to overlap. The oyster farm came with all this plastic gear: the ropes, the zip ties and the floating bags used to cultivate the oysters. However, a big part of my life was to reduce the amount of plastic I was handling and search for viable alternatives.

What size is your farm, and what species do you produce?

Barrows and her colleagues harvest 40,000 oysters by hand each year

I have three acres under cultivation. Our licencing process in Maine is slow, but I hope to double the size.

How many oysters do you produce by count each year, and what kind of production system do you operate?

I am producing 40,000 oysters per year. We work in a small team; two other women and I work in a boat. We harvest the oysters by hand, but we aim to mechanise some processes. We set up a solar-powered tumbler last fall, replacing the manual sorting that we have done to date.

Can you provide some details about the different stages of cultivating an oyster?

The oyster season runs from April to May, then November to December each year. I purchase my 2.5-millimetre oyster seeds from a hatchery in mid-coast Maine. I put those seeds into cedar boxes covered with stainless steel window screens, built from scratch, and put those into the water.

Barrows places the spat into the 2-millimetre window screen baskets and then upgrades to mesh as they get larger

We have all the different sizes of oysters on the farm, which we are constantly tending, sorting and upgrading into larger mesh bags. We place spat into the 2-millimetre window screen and then upgrade into 5 mm, 10 mm, 14 mm, 19 mm and 25 mm bags as they grow.

We shuffle things around and handle the oysters, physically shaking the bags to help break off new shell growth and create robust oysters. It's a short rigorous season of intensive harvesting and maintenance. It takes around two-three years for oysters to reach market size.

It's physically demanding work. We look forward to having a tumbler as part of a weekly cycle to flip and sort our oysters. Every week, we have multiple days of harvesting, and we sell a few thousand oysters at wholesale, retail and our oyster pop-up event at the indoor farmers' market. I also have a small retail space on my porch at my house, where people pre-order oysters and come pick them up at their convenience.

We are lucky to live on an island with water that can grow oysters well. We have all the elements we need right here in the ocean and we might as well use our strong currents and our tidal cycle to grow food.

The oyster season runs from April to May, then November to December each year

Do you have any developments underway?

We are entering the second year of our two-year grant for designing, building and trialling plastic-free gear. In the R&D phase, we tested some materials – stainless steel, cork and cedar – tried different treatments like plastic-free paints and used vanilla ropes, which have been around for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. We are working with partner farms up and down the Maine coast to try the gear at different sites, because every area has different environmental pressures.

At present, we are working on an innovative Mycobuoys Project in Maine. We are growing mushroom buoys using agricultural crop waste and fungal mycelium. We are exploring different treatments on them to see how they hold up and produce mushroom-based buoys for bigger cages. It's a biologically compatible alternative to expanded polystyrene (EPS) buoys.

Sustainability is a driving force in my business – from cultivating the oysters to harvesting, using green energy and selling oysters in paper bags. As an oyster farmer, I rely on clean, pollution-free water to grow an animal that people are willing to eat. That's why I am taking baby steps to grow my business conscientiously with a zero-carbon footprint.

Barrows hopes that her business will maintain its low carbon footprint as it grows

What type of gear would you most like to have on your farm?

I would love to build or have a custom-made upweller system that could use solar polar and plastic alternatives for growing the oyster spat. Most larger farms get small oysters that rapidly grow in floating upwellers. I am looking for ways to do that without plastic and not just relying on the energy grid here.

What impact has your oyster farming had on your local marine environment?

I feel that having a few hundred thousand oysters in the Cove has helped with the water clarity. I believe the fish species have diversified a bit, as I am seeing both short- and long-nosed sturgeon come back into the area.

What challenges have you had to overcome?

There are constant challenges and many stem from not having a background in business. I had to learn money management, grant writing and people management. I overcome these by leaning on other businesspeople and asking many questions. The beauty of aquaculture is that the oyster community is very supportive and helpful to each other.

Since Barrows didn't have a background in business, she had to rely on a supportive aquaculture network

Another challenge was finding workers and a place for them to stay, as Maine has serious housing issues. I needed to find an affordable place for them to commit to the time that I needed. Luckily some local families provide rustic housing.

You have also managed to collect thousands of water samples from all the world’s oceans. Could you tell me more about this research project?

The five-year project started in 2013, when I worked for a Montana-based nonprofit organisation called Adventure Scientists. I designed a Global Microplastics Initiative and helped recruit and train adventurous people – for example, who were rowing from California to Hawaii, or were kayaking around the Northwest Passage – to collect water samples across the world’s oceans, rivers, lakes and streams. They would follow my protocol and then ship water samples to me, and I would process them in my lab in Maine.

I also did a two-year study in the Gallatin mountain range in Montana, where the organisation was based. We sampled 1-litre of surface water for all the microplastic research. We collected samples from the Gallatin Watershed, Gallatin water beach into Missouri-Mississippi river system in the United States, the largest freshwater system, where we found widespread microplastic contamination in service water.

In 2016 we expanded to freshwater, meaning that we collected 2,677 samples over four years from water on every continent, every ocean and sea.

Barrows research has created a database to help inform legislators and other organisations as they work towards reducing plastic in aquatic environments

It was an eye-opening project, as we found microplastics in all the world's oceans and in most freshwater environments. This project gave me an insight into how we could change our relationship with plastics in the water. I assembled a database, which created localised campaigns and other organisations, such as the World Health Organisation (WHO), to use the database to help legislation and reduce plastic in their communities.

What advice would you give to others looking to establish an oyster farm?

Start small and try not to overextend beyond your means because farming always has unknown chaotic factors that can wipe out your crops. If you are failing on a small scale, it’s better than doing so on a big scale. Start within your means, ask lots of questions, do your homework and be good to your neighbours.

How do you see Long Cove Sea Farm evolving in the years to come?

We aim to open up a new wholesale account and increase harvest weekly with the help of an internship programme and a full-time farm manager. I am figuring out what makes sense for a business of my size and where to put our energies. Perhaps, more into the pop-up events because of the profit margins.

I also aspire for Long Cove to be the model of how to establish and grow a commercial business free of plastic. I don’t know if that is possible, it may end up being a hybrid, but I have to try.

I hope to have a small amount of continuous expansion and diversification into some seaweed species. As seaweed is a winter crop, this will ensure employees year-round.

What hopes do you have for the future of oyster aquaculture in the Gulf of Maine?

We will continue to see an increase in oyster farms here in Maine and little pushback along the coast. We hope to sculpt legislation and bylaws to encourage the smaller farms and strengthen the diversity of people in the industry, rather than having these large-scale, 100-acre farms monocropping off the coast.

Barrows hopes to grow seaweed as her oyster farm expands

Oysters are important species for the future of protein in our oceans and human consumption. They are healthy and lower down the food chain. It would be awesome to see more aquaculture cultivation and access to locally cultivated seafood. I encourage young farmers to get into the industry and think about how it is shaping the coast of Maine and the future of sustainable fisheries.