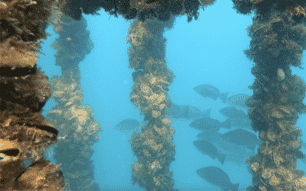

Oyster restoration has long been a priority for The Nature Conservancy. Shellfish serve as nature’s water-purification system, filtering sediment, algae and excess nutrients from the water. Their reefs provide nurseries and feeding grounds for fish and other commercially and recreationally important species.

Over the past 200 years, we’ve lost more than 85 percent of our oyster reefs globally due to overharvesting, nutrient pollution and other extractive human activities. As these oyster reefs have disappeared, so too have the vital services they provide to coastal ecosystems and communities.

© Erika Nortemann / TNC

Eutrophication – a process where high levels of nutrients in waterways cause harmfully low oxygen conditions – is a significant issue plaguing estuaries worldwide. As much as 65 percent of United States coastal water bodies and estuaries are considered degraded by excess nitrogen and phosphorus sourced from urban and agricultural runoff, wastewater treatment plants and air pollution.

The Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in the United States, is highly eutrophic, with 331 million pounds of nitrogen flowing into the bay each year. Due to overharvesting and habitat destruction, the bay has also lost roughly 99 percent of its native oyster populations, further hindering its ability to recover. A healthy bay is important for surrounding communities, with benefits including air and water filtering, the enhancement of property values and protection from floods and hurricanes.

© TNC

To help combat these pressing issues, The Nature Conservancy and our partners have engaged in some of the world’s largest oyster reef restoration in the bay for the past decade. While we are pleased to see the great strides already made, we also recognise the need to identify new cost-effective tools to help accelerate bay recovery efforts.

Simultaneously, the oyster aquaculture industry in the Chesapeake Bay is growing rapidly – in the last 10 years, oyster growers have increased their market by more than 600 percent, growing from 5 million to almost 40 million oysters sold per year. While there have been concerns about the impact of the industry’s growth on the bay, very little research on the potential ecological benefits exists.

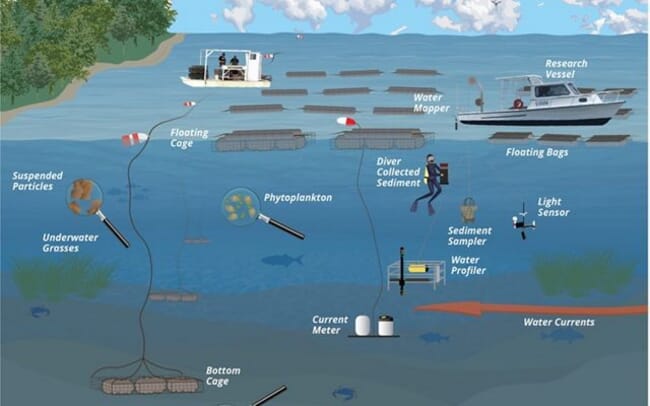

With this in mind, we recently embarked on a new study to better understand how oyster aquaculture may be able to help make water in the Chesapeake Bay cleaner, faster – all while providing sustainable seafood and green jobs. Throughout the two-year study, we partnered with the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) and four oyster growers – Big Island Aquaculture, Chapel Creek Oyster Company, Lynnhaven Oyster Company and White Stone Oyster Company – to develop a better understanding of the specific connections between oyster aquaculture, water quality and ecosystem health.

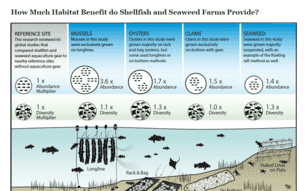

After sampling and studying environmental variables at each of the four oyster farms – including water currents, water clarity and chemistry and sediment type (as well as the creatures that live in it) – our research indicated that oyster aquaculture is a low-impact way of producing animal protein.

© TNC

Data suggest that the oyster aquaculture industry can help to restore water quality in our rivers and bays. For every 100,000 oysters grown and harvested annually, 6lb of nitrogen and phosphorus pollution are removed from the bay. Oyster farms may also reduce wave energy and help protect vulnerable shorelines.

We understand that the benefits provided by oyster aquaculture alone cannot save the health of the Chesapeake Bay. Success will depend on the combined efforts of a broad group of stakeholders and our ability to rethink existing methods, including improving land-based farming practices to reduce runoff and nutrient pollution, improving water treatment facilities and continuing support for traditional restoration efforts.

Nevertheless, it is our firm belief that when done right, oyster aquaculture can play a meaningful role in improving water quality, protecting vulnerable shorelines and creating sustainable protein – all while supporting coastal livelihoods and ecosystems.

More information on the study, the growers and the final reports can be found here.