Researchers developed a metallic fingerprint-based technique to detect and measure nanoplastics in organisms © Nutri Tech

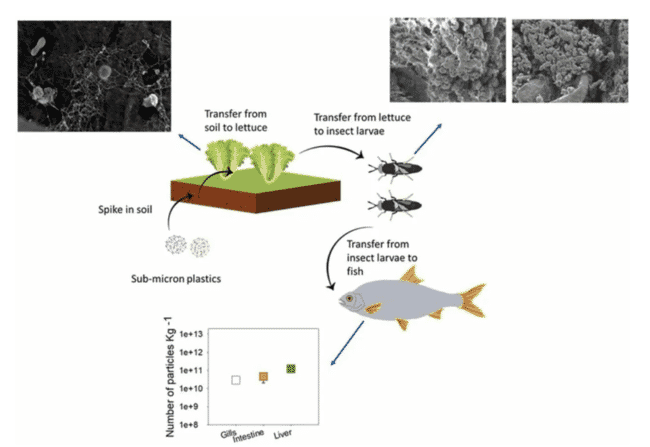

Researchers at the University of Eastern Finland have developed a novel, metallic fingerprint-based technique to detect and measure nanoplastics in organisms. In a recently published study, they applied the technique to a model food chain made of three trophic levels – where lettuce was the primary producer, black soldier fly larvae was the primary consumer and insectivorous fish (roach) was the secondary consumer. The researchers used commonly found plastic waste in the environment, including polystyrene (PS) and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) nanoplastics.

Lettuce plants were exposed to nanoplastics for 14 days via contaminated soil, after which they were harvested and fed to insects (black soldier fly larvae, which are used as a source of proteins in many countries). After five days of feeding with lettuce, the insects were fed to the fish for five days.

Using scanning electron microscopy, the researchers analysed the dissected plants, larvae and fish. The images showed that nanoplastics were taken up by the roots of the plants and accumulate in the leaves. From there, nanoplastics were transferred from the contaminated lettuce to the insects.

© Abdolahpur et al (2022)

When the team imaged the insects’ digestive systems, they found that both PS and PVC nanoplastics in the mouth and gut – even after the insects were allowed to empty their guts for 24 hours. They noted that the number of PS nanoplastics in the larvae was significantly lower than the number of PVC nanoplastics. This finding was consistent with the lower number of PS particles identified in the lettuce.

In the final element of the food chain trial, the researchers fed the contaminated insects to the fish. After the fifth day of feeding, the researchers examined the fishes’ gills, liver, brain and digestive tissues. They identified nanoplastic contamination in the gills, liver and intestinal tissues – but did not find nanoplastic particles in the brain.

“Our results show that lettuce can take up nanoplastics from the soil and transfer them into the food chain,” lead author Dr Fazel Monikh of the University of Eastern Finland said.

Background to micro and nanoplastics

The concern about plastic pollution has become widespread. In recent years, the scientific community has learned that mismanaged plastics in the environment break down into smaller pieces known as microplastics. These can degrade further to become nanoplastics. Due to their small size, nanoplastics can pass through biological barriers and enter organisms.

Despite the growing body of evidence on the potential toxicity of nanoplastics to plants, invertebrates and vertebrates, our understanding of plastic transfer in food webs is limited. Little is known about nanoplastics in soil ecosystems and their uptake by soil organisms, despite the fact that agricultural soil is exposed to different sources of nanoplastics from atmospheric deposition, irrigation with wastewater, applying sewage sludge for farming and using mulching films.

Measuring the uptake of nanoplastics from soil by plants, especially vegetables and fruits in agricultural soils, is crucial to learn whether nanoplastics can make their way into the edible parts of plants and be introduced into food webs. After this initial introduction, nanoplastics may be able to move up trophic levels into organisms like fish – which potentially find their way onto our plates.

“[Our results indicate] that the presence of tiny plastic particles in soil could be associated with a potential health risk to herbivores and humans if these findings are found to be generalisable to other plants and crops and to field settings. However, further research into the topic is still urgently needed,” Dr Monikh concludes.