McIntosh, who joined CP Foods in 2001, has been responsible for some of the most notable advances in shrimp culture over the last 20 years – including building the first zero water exchange farm in Belize, and the first biosecure shrimp farm in Latin America. Most recently he has been overseeing the development of a pilot shrimp farm in a former citrus grove in Indiantown, 40 miles from the coast of Florida, that aims to produce up to 1,000 tonnes of shrimp annually with zero waste. He hopes it will act as a blueprint for a series of Homegrown Shrimp farms, close to areas where there is the most demand for quality shrimp. As he explained to delegates at a webinar run by the Asian-Pacific Chapter of the World Aquaculture Society today.

In particular he focused on the dangers of reducing the bacterial complexity of RAS.

“In the beginning of the 1980s we ran hatcheries and we didn’t really use disinfection, we used filtration for the most part and we did OK. In the first hatchery in 1988-89 when we thought we were advancing the technology by introducing disinfection, all of a sudden the hatchery had many, many problems. Sometimes we’d have successful tanks but oftentimes our tanks would fail. And I started thinking without really understanding anything why is this tank good and that tank bad – what’s the difference?” he recalled.

“My conclusion to myself was that it had to be microbial – everything else was constant. And so, if I could see good microbes in tanks routinely I could probably increase the probability of a successful tank,” he added.

“Another experience with disinfection would have come along with EMS [early mortality syndrome] – the first time I saw EMS was back in 2009 in Fujian, in China, and then I watched it move and I noticed over time that every two of three years there was a pattern – it always seemed to correspond with disinfecting ponds and the more we disinfected the more we got EMS. I actually took those observations into my little trial laboratories and my genetic challenge centres and actually determined that if I had a more complex ecosystem I would have less chance of the Vibrio parahaemolyticus bacteria taking over and have fewer problems. If I simplified the ecosystem by disinfecting, I would have the worst problems,” he explained.

“Then we talk about recycling and we’ve always known, even from the 1990s, when I put recycling in our maturation tanks, if I recycle the water I get a better result than if I have flow-through. And again that is because of stability – stabilising microbial populations, stabilising environmental populations. So stability was very, very important to this whole process,” he added.

McIntosh then went on to explain how he applied these findings to Homegrown Shrimp.

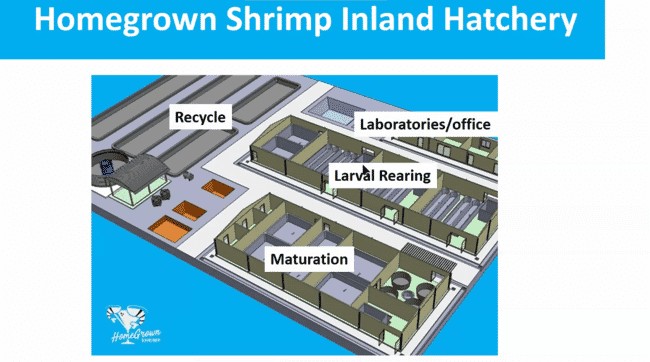

“Homegrown Shrimp was basically established as a conceptual farm – culture shrimp anywhere, culture shrimp anytime of year, completely biosecure farm and no discharge of waste water,” he noted.

McIntosh’s vision for the farm, which is currently nearing completion, is for the shrimp to be produced in optimum conditions – with the water being maintained at a constant 30 °C.

Due to regulations and the landlocked location of the farm they are not permitted to discharge any water, and have to make up their water using groundwater and adding salts.

“Of course that’s an expensive process, if you discharge it, but we have to reuse it so we have to recycle,” he explained.

He then went on to list a few of the reasons why recirculation is a good idea.

“It’s an inland shrimp hatchery and farm and uses seawater made of mixing artificial salt with potable fresh water, so it’s too expensive to do anything but recycle or recirculate," he noted.

He also emphasised the importance of using specific pathogen-free (SPF) shrimp.

“SPF is a critical component of anything and everything I do and it’s what makes Homegrown – an inland farm with no farms around it – very easy to operate. It’s much like my SPF broodstock breeding facilities. Culture there is easy – we get 95 percent survival in our nucleus breeding facilities. We don’t use seawater, we use artificial water that’s recycled. I’ve used the same water in our nucleus breeding for 15 years, so we have recycled it many, many times." he observed.

“And recirculated water is microbiologically more stable and results are superior – in maturation we know we get higher fecundity when we recycle or recirculate and higher survival,” he explained.

“At Homegrown we’re going to use a new strain that I developed just for indoor farmed in US and Europe. I call it the Bolt, it’s named after Usain Bolt, a very fast human being, so this is a very fast-growing shrimp. I know that it’s the fastest-growing shrimp in the world,” he claimed.

Indeed, he then presented results from trials, showing that the shrimp can be grown to close to 30 g in only 47 days – about 10 days quicker than the average – if the cycle is blessed with ideal conditions.

Water treatment methods

McIntosh then went on to describe the water treatment process that he’s developed.

“We have to disinfect for specific pathogens but when we disinfect we get rid of all of the complex, mature bacteria and because we’re changing water all of the time, we basically stay in a state of flux. So I developed the idea several years ago of mature water conditioning,” he explained.

This involves installing conditioning tanks containing “a complex of tapioca flour, urea, ammonia, phosphate, sodium silicate and some bacillus probiotics where we add the same amount of material every day and everyday we go in and we basically partial harvest the floc out of the tank and that is added to the disinfected hatchery water”.

“Originally the hatchery managers were shocked that you would want to add this dirty contaminated water – it did have bacteria and diatoms and amphipods it wasn’t ‘disinfected’ water, but the results of doing this were that the water that had mature water [added to it] stayed clear. They did not form biofilms in the tank, as the normal disinfected water did. And, as a result, our survival rate increased by 10 percent and the size of the shrimp increased, meaning they were healthier animals. So, after a month of this, the hatchery was sold on the idea that, yes, we disinfect the water and get rid of specific pathogens, to make sure there’s no EHP, no EMS bacteria, make sure there are no specific pathogens and then we dirty the water back up with water that has been matured.

“To start a mature water tank like this takes 3-4 weeks, so once we have it started we partially harvest it every day re-add more nutrients and then continue the harvest and putting that mature floc in the disinfected water in the hatchery and it really has stabilised the hatchery – what used to be a less stable situation,” he added.

The Homegrown hatcheries have been designed for operation by only two people – in order to cut down on labour costs in the US and Europe, the two areas Homegrown aims to be established in first.