© Global Salmon Initiative

Despite its rapidly growing prevalence, aquaculture as an industry remains controversial, particularly amongst environmentalist researchers and activists. Renowned ecologist, author, and professor Carl Safina, recipient of the prestigious MacArthur fellowship and founder of the Safina Centre - a US-based environmental non-profit - is one such aquaculture sceptic. In a recent essay, Safina labels the problems of the industry as symptomatic of our food systems as a whole, which “reflect failures of care and conscience throughout."

One of the greatest problems posed upon the Earth’s ecosystems by human food systems is, according to Safina, the exponential growth of the human population itself.

“Humanity and the planet simply cannot stand a continuing growth programme. The limits to growth were delineated decades ago and the economy is breaching planetary limits. The global population of wild animals has declined 70 percent in my lifetime. The human population has tripled,” states the 69 year old.

“We cannot have security if we refuse the idea of stability; stability of the population and global economy. Constant growth is constant insecurity. It’s guaranteed to add to the world’s constant turmoil until it hits its dead end. That project is broken,” he adds.

An alternative future for aquaculture

Even if the human population were to stabilise overnight, 8 billion people is still a significant number to feed and aquaculture, like it or not, is playing an increasingly important role in achieving that. With that in mind, Safina outlines the ways in which he believes the aquaculture industry needs to change in order to meet global food demands whilst reaching true sustainability and reducing its environmental impact to zero.

“As a first step, any fish or shrimp aquaculture should be on land, in facilities constructed on already built and degraded land, with filtered outflow to prevent diseases and parasites from getting out,” he says.

Easier said than done may be an understatement here, however recent analysis shows that investment trends strongly favour next-generation land-based production systems over traditional methods. With cutting-edge technologies, such as recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) and hybrid flow-through facilities, steadily increasing in number, an industry which can operate with minimal negative impacts on its surrounding ecosystems may just be viable.

Additionally, legislative reforms which ban cage aquaculture have been gaining popularity, with British Columbia, California, and Alaska all employing similar restrictions on the grounds of environmental conservation. Considering this, it may not be that far-fetched to imagine the aquaculture industry of the future as entirely land-based, if such restrictions continue to spread. However, producers currently adopting these methods are few and far between, with the technology still facing significant financial and animal welfare challenges.

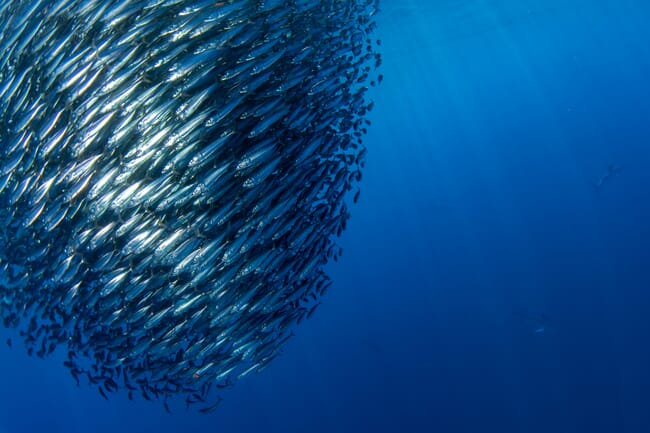

Another aspect of the aquaculture industry which Safina condemns is its reliance on wild fisheries as a source of feed ingredients. Recent research has suggested that the wild fish inputs of salmonid aquaculture operations may be twice as high as their biomass outputs. Even as alternative ingredients - such as those consisting of plant and insect proteins and oils – gain in popularity, much of the industry seems to use these ingredients to supplement feed production, as opposed to using them as a tool for phasing out dependence on already struggling wild fish populations.

“Given what we see and the problems it causes, I’d like to see no aquaculture that raises any animals that require feed. The only aquaculture I’d like to see is for the things that can actually have positive effects on surrounding systems, and those things are kelp and bivalves,” he states.

“Relatedly I’d like to see no reduction fisheries operating for any of the world’s animal farming, whether aquatic or terrestrial. We all know that reduction is a waste of food that could go straight to people, and that it takes food from wild fishes, birds, and mammals and undermines wild production of predatory fish such as tunas and so on, that humans like to eat. Wild productivity should be left in the wild, supporting wild animals and well-capped, truly sustainable capture fisheries,” he adds.

How do we get there?

Whilst remaining staunchly critical of aquaculture, Safina isn’t calling for a blanket ban of the industry, but rather for a series of significant changes to the sector and to the way seafood is produced as a whole.

“Of course it can exist on a global scale. Sustainable production is very simple: it means putting a limit on production so that it can be sustained. It means not killing fish faster than they can breed. It means maintaining massive forage fish population bases. It means limits,” he explains.

The path towards truly sustainable aquaculture may be long and challenging but, as is often the case, it is taking the first step that can seem the hardest. Safina suggests that for meaningful change to be realised within the fisheries and aquaculture industries, the onus rests firmly with government, which can incentivise progress through regulation, enforcement, and trade standards. This in no way removes the responsibility from the shoulders of the individual who can, and should, make ethical decisions towards seafood consumption but, Safina argues, this will never be enough to make change on a wider scale.

“This is a little like the petroleum industry insisting that the solution to plastic pollution is the responsibility of the consumer. Consumers will never care enough, be educated to care, or amount to enough pressure,” Safina says.

“Individuals should stop being individuals and join organisations. Consumers can pressure governments to make positive change, but change based on grassroots efforts is usually the result of a few activists within public-interest policy or environmental organisations waging well-organised legislative campaigns. Yes, we should all buy ethically, but change won’t be created at the seafood counter. It needs to come bigger and higher than that,” he adds.

Reflecting on the role of government in achieving sustainable fisheries and aquaculture industries, Safina highlights the changes enacted by the United States’ Sustainable Fisheries Act of 1996, which built on the Magnuson-Stevens Fisheries Management and Conservation Act. Prior to the creation of these laws, the fishing industry around the coast of the US was governed only minimally, with devastating consequences to the marine environment. The advent of the Sustainable Fisheries Act required management to rebuild the overexploited fish populations to biologically sustainable levels which has resulted in positive repercussions not only for marine ecosystems, but also for coastal communities and fisheries and aquaculture industry stakeholders.

“The US has done a pretty good job since the Sustainable Fisheries Act, and that is a reasonable model. Fish don’t care how many people there are. People need to care how many fish there are, or else we will continue to have what happens when we don’t care: we have the depletion, habitat destruction, worker abuse, and other ills that have prompted this conversation,” Safina concludes.