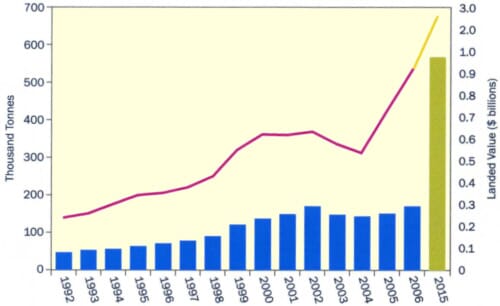

On the face of it, Canadian aquaculture is a resounding success story. This year it became a billion dollar industry, employing over 16,000 people in 10 different provinces. The industry has reached right into the heart of rural Canada, providing new opportunities for Canada's aboriginal peoples. It now accounts for approximately one third of Canada's total fisheries value. However, a closer inspection reveals an industry hampered by unforgotten incidence, the full effects of which might only now be coming to light.

It has taken 20 years for Canadian aquaculture to reach this stage. By comparison with other sectors this can be seen as remarkable progress, but those within the industry believe that its true potential is not being fulfilled. Perhaps they are right. Canada boasts the world's longest coastline, its farms have excellent proximity to markets and the products hold well-established reputations for safety, sustainability and quality. The work force is skilled, the research is in-depth; demand is ravenous and opportunities for expansion are vast. Aquaculture already takes place in ten provinces of Canada, of which British Columbia, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are said to be big global players. On paper, Canada should be a real world leader in aquaculture, yet the sum-total of its entire production amounts to only 0.2 per cent of global output.

The Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance aims to change all that. The recent release of their White Paper Brief, A Canadian Opportunity, claims Canada is poised to become a world leader in aquaculture. It goes on to describe "what it will take to get there - and why it matters." According to the report, if the correct action is taken Canadian aquaculture could treble by 2015. The alliance estimates that aquaculture can earn C$2.8 billion and employ 50,000 people. This is a big demand of the industry and many may ask that if such growth patterns are possible then why have they not taken place before. According to the White Paper the answer is embroiled within a legacy of past controversies.

The industry is being hampered by "public attitudes towards aquaculture" and "outdated information," says the report. Accordingly, "most of today's criticisms of the industry are based on environmental problems and practices that are no longer current." But whilst the media have a responsibility to update their information when industries provide open and honest information, some things are not so easily forgotten.

Between 1990 and 2000 Canadian aquaculture suffered from an average of 90,000 fish escapes each year. Although there have been improvements in the technology since then, 30,000 fish still managed to escape in just one incident in 2008, gaining a great deal of media attention. There is still no conclusive evidence that fish farms have any effect on wild fish stocks, but many believe that the rapid collapse of salmon runs in British Columbia is a direct consequence of their presence. Proponents of this view argue that escaped fish, parasites and disease lie at the root of this collapse.

There is contradiction in the goals of the expansion plan in that the British Columbian First Nations -- said to be the ones who will benefit from investment -- have a history of legal action against government agencies in response to what they consider to be the impacts of farms on wild fish in their territory. The Kwicksutaineuk/Ah-Kwa-Mish First Nation's recently filed a class-action lawsuit against salmon farms and the B.C. government acknowledged the risks of open-net cage salmon farming by implementing a moratorium on B.C.'s north coast.

B.C. Salmon Farmers' Association refute the claims against the impacts of aquaculture and say that global warming is to blame for salmon stock collapses. According to the association, changing ocean conditions have already made rivers and oceans warmer, prompting early spring run-off and disrupting the lifecycle of the salmon.

* "Expansion is impeded by a maze of government legislation that has resulted in regulatory duplication, increased costs and ultimately, reduced marketplace competitiveness" |

|

White Paper Brief

|

Sustainable salmon production is a major issue for Canadian aquaculture. According to The White Paper, it is responsible for 66.7 per cent of overall aquaculture. If sustainability cannot be ensured, then any expansion will have to focus on exploring the potential for other forms of aquaculture, of which Canada has many. Currently Mussels account for 15.8 per cent of overall aquaculture, oysters for 8.7 per cent, and trout 3.4 per cent. The remaining share of the industry is made up of char, tilapia, sturgeon, cod, halibut, abalone, scallops, clams, geoduck, quahog, abalone and kelp. But if these industries are to strive then something needs to change.

"Aquaculture industry expansion is impeded by a maze of government legislation that has resulted in regulatory duplication, increased costs and ultimately, reduced marketplace competitiveness," says the White Paper Brief. "It is governed by no less than 73 separate Provincial and Federal statutes and regulatory processes, many of them working at cross-purposes." The report says that current rules and governance need to be modernised if the industry is to have any chance of reaching its full potential.

Rules over water tenures are seriously holding back new companies. According to the White Paper Brief, a marine clam farm tenure can take five years. "Given the biological nature of their business, finfish and shellfish growers need timely, dependable permitting decisions to plan for new operations." The reports also says that site access, for both finfish and shellfish farms, causes many detrimental issues.

There are signs that Ottawa is listening. "The last federal budget allocated C$70 million over five years towards improved governance," says The White Paper. This will be achieved through regulation, certification and innovation. Now that the Chilean aquaculture market has been weakened due to a series of biological situations the opportunity for expansion -- especially in the US -- is ripe. Unfortunately marketing support through Canadian Agriculture and Food International has been terminated. This comes at a time when Canada's main competitors -- Norway and New Zealand -- are receiving generous government support for market outreach.

According to the White Paper Brief, the aquaculture industry is also in need of new infrastructure to replace inadequate wharves, roads and bridges. Telecommunications and loading/unloading facilities need to be improved. There is a need for investment in research and development to help guide the industry towards cutting-edge green production technologies that reduce the industries environmental impact. Investment of this kind would provide a boost to the many emerging aquaculture species, whilst innovating new industries in alternative feeds and the possible commercialisation of polyculture.

"Aquaculture isn't looking for and doesn't need subsidies," says The White Paper. "It needs to be treated equally with older sectors of the economy, such as agriculture and the wild fishery." Canadian aquaculture is asking for a chance. It is clear what the industry expects of Canada, the question now is: what do Canadians expect of it?

May 2009