“It’s a good protein source, but there’s nothing special about insect meals in my book,” Auburn University professor Allen Davis said during a recent panel discussion at Adisseo’s The new green is blue event. The session, which also included analysis from Rabobank seafood analyst Gorjan Nikolik and University of Tasmania professor Chris Carter, debated whether insect or single-cell proteins would be the sustainable aquafeed ingredient with staying power.

The panel agreed that insect protein companies are making incredible advances and capitalising on their sustainability and waste converting potential. However, the industry faces significant hurdles when trying to scale up. There are some nutritional limitations with insect protein as well – making it difficult to determine when insect proteins will be widely included in commercial aquafeeds.

Because of these factors, Davis and Carter believe that single-cell proteins (SCPs) and microbial proteins will be the aquafeed industry’s long-game. Though the sector is in its infancy, microbial companies have the potential to tailor nutrients and provide specialised ingredients for aquafeeds. This is an attractive prospect for aquaculture nutrition; but the bacteria-based feeds need to be produced at scale first.

Insect proteins vs SCPs

The panellists agree that the buzz around insect meals is warranted. Carter said that consumers like the idea of using insects to bioconvert waste products into high-quality protein sources for the feed industry. But Davis told listeners that nutritionists won’t use insect-derived ingredients solely for their waste processing abilities. They have to be competitive on other grounds as well.

Davis acknowledges that there are some bioactive compounds in insect meal that make it attractive for feed companies, but the industry generates a lot of waste products. From a nutritional standpoint, insects provide good protein – but their ability to offer nutritional enhancements is limited.

Both Davis and Carter were sceptical about the insect industry’s ability to scale up. Current production volumes in Europe and Asia are low. The industry also tends to tight-lipped when it comes to timelines – nutritionists don’t know when insect companies will be ready to produce a consistent ingredient supply.

Carter and Davis also expressed some misgivings about the insect industry’s bioconversion pitch. In some cases, it runs the risk of turning into a gimmick. The ability to turn waste meals and waste products into feed sources is useful, but some insect startups are feeding their soldier flies products that could go directly into aquafeed. When this happens, the bioconversion doesn’t serve an obvious benefit. “If something can go directly into animal production, I say we should give it directly to the animal instead of putting it through a bioconversion,” Davis said.

Both researchers felt that the aquafeed industry will move towards SCPs in the future. Carter said that the bacterial feed ingredients can give nutritionists flexibility and allow them to address specific nutrient requirements. “In my view, that’s where the future is,” he said. Davis largely agreed, saying that, “with bacterial biomass, you’re basically unlimited in how you can manipulate them. With insect meals, you’re much more limited.”

Though the existing SCP industry is small, Carter and Davis told listeners that it might not face the same scalability issues that insect entrepreneurs are currently negotiating.

A banker’s take on the insect and microbial protein industry

In Gorjan Nikolik’s view, the insect sector is set to take off in the next decade – but it’s difficult for industry watchers to identify where potential facilities will be built or what their capacity will be. Leaders in the insect space tend to be, “young, energetic, have access to capital to some extent and have a great future to build on.”

Nikolik said that in his experience, Western insect producers tend to demur when asked when their facilities will come online. He used a French mealworm company as an example: it has a promised capacity of 100,000 tonnes, but the company is keeping quiet about the construction time. He expects that it might come online in the next two to five years.

Nikolik said that more black soldier fly (BSF) plants will be built in the West, but that the facilities will have a fairly small production capacity (1,000 to 5,000 tonnes per year). BSF plants in Asia tend to be smaller again, only producing a couple hundred tonnes per year. This echoes the scaling difficulties mentioned by Davis and Carter. Every insect company Nikolik reviewed has plans to scale production to a few thousand tonnes of insect meal per year, but there isn’t any word on how this will be realised.

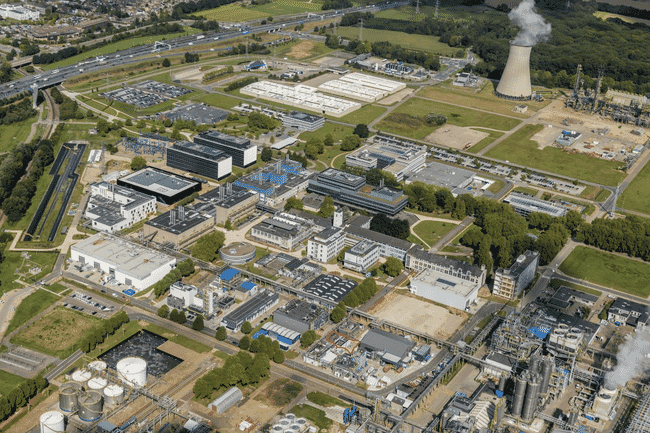

As it stands now, SCPs and microbial plants produce a few hundred tonnes of product each year. But Carter, Davis and Nikolik said that on paper, the segment has great potential despite this small output. Plans for microbial protein facilities show huge structures with enormous capacity – costing between $100 million and $200 million per site. The production potential of insects is dwarfed in comparison.

Nikolik believes that SCPs will have a good cost structure once they’re at scale. Though there are multiple levels of scale-up needed, there’s reason to believe that microbial plants can produce 100,000 tonnes of protein each year once the process is optimised. He also thinks that the industry can meet product consistency benchmarks and keep costs per tonne low. This will make it an attractive option for feed formulators and could spur its adoption.