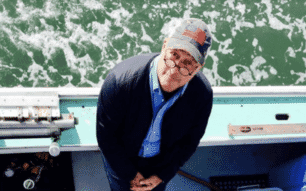

What inspired you to devote your life to the wellbeing of the oceans?

I probably have a bit of a unique perspective in the ocean space, because I've literally grown up in it. I could swim before I could walk and learned to dive with scuba from my grandfather, Jacques Cousteau, at the age of seven. Though I have seen the degradation of the marine environment, I believe that we can aspire to leave our children an ocean abundant with life and reverse the flow of plastic away from the ocean. My work now consists of public speaking, advising nonprofits, government and industry, as well as collaborating with communities, the media, and forward-thinking brands. It was this drive that led me to form Oceans 2050.

We will lean heavily on our scientific adviser. Everything that we will do will be based heavily on science and what science says is possible. Our goal is to democratise the ability to create change within the ocean community. This is essential because right now it's dominated by a few big players, and they're doing good work, but we really need an army of solutions for an army of problems. There are so many other players out there who are doing really good work. Ocean 2050’s goal is to enable and accelerate their work and their leadership, to bring visibility to their efforts and get support for them.

We're not a traditional nonprofit that focuses on funding our programmes and producing an annual report. We're not a business for hire. We're foundation-owned, a social business focused on social and environmental good.

We've already launched a project for developing the Voluntary Carbon Protocol for seaweed aquaculture and have 20 farms participating, including a 300-year-old Japanese seaweed farm and we’d love to have other farms participate.

One thing we will be drilling into is figuring out how much carbon a seaweed farm sequesters. We are going to do DNA testing to see how the farms, once they were established, changed the biodiversity of the area. This is a place where we can develop a market for public good – one that spurs seaweed aquaculture and makes it easier for them to get social licence and investment to scale around the world.

One key ingredient missing is compensation. These farmers have to be compensated for their work. Oceans 2050 wants to bring compensation to stewardship rather than exploitation. That's really important. We need to create a powerful shift and create catalytic tools that bring transformative change.

What are the most crucial issues facing the oceans?

Coral reefs are extremely urgent. They are the source of biodiversity for the oceans. They are the most critical ecosystems on the planet. With business as usual on our part, they will likely collapse. The clock is ticking in the race to find solutions to rebuild and restore our coral reefs, obviously fighting against climate change and all these other negative impacts. We're looking at new technologies that can give us solutions. There are a lot of exciting new technologies out there for coral reefs, such as ocean afforestation – whether it's seaweed aquaculture or wild ocean forests. We urgently must use them to accelerate that transformation.

Brazil is getting rid of their regulations to protect mangroves, which is deeply disappointing. Ocean forests of any kind are extremely important for blue carbon and addressing climate change. Our goal is to ensure that we can work to bring back our wild ocean forests into their former historic footprint, if possible. This can also be through the expansion of regenerative aquaculture, of species such as seaweed, because ocean forestation is one of the key drivers to restore abundance.

We also need to develop innovative technology to ensure the transparency and traceability of wild seafood and to improve how we manage our farms, including producing feed for aquaculture. Through my work with Oceana, I've learned that it is possible to rebuild our wild fisheries by making smart policy decisions, expanding marine protected areas, using science-based quotas, and reducing bycatch. We need to transform our global fisheries, freeze out the pirates, and reward legal fishermen. We need to find ways to contribute to rebuilding our oceans and not continuing to rob them of life. In tandem, we need to transform aquaculture in an effort to make it more sustainable.

Which body of water is most special to you and why?

My childhood memories are really concentrated in the south of France. Sadly, the Mediterranean has declined so much since my childhood. So many of the little creatures – like shrimp, little sea urchins, and crabs – that I would find have disappeared. As connected as I felt to this beautiful ocean, the Mediterranean now has like four times the concentration of microplastics of any ocean in the world. It's been a very rapid decline because it's a closed environment and the water circulates extremely slowly. I think it takes 100 years for the water to change over in the Mediterranean as it only has two points of access. Basically, whatever goes into the Mediterranean stays in the Mediterranean.

What are the most crucial issues facing our oceans at the moment?

I've watched a steady decline in ocean abundance over the course of the past 40 years. The headlines have just kept coming throughout my life on the losses that we are accruing in ocean diversity, ocean health and abundance. When I had my kids, I knew it was time to really get involved.

The prediction is that, by 2030, we could have more plastic in the ocean than fish. From my perspective, it seems that we've been fighting exponential loss with incremental change, and that's part of the reason we've been talking a lot about conservation and sustainability. When I was born, 90 percent of the oceans were healthy and abundant. Today, less than 50 percent of the oceans are still healthy and we lose one percent more each year. We have almost reached a tipping point that is difficult to come back from. We cannot face our children and tell them that that's the path we're on and that's where we're going. I cannot see this as an inevitable outcome.

How well-informed are seafood consumers?

We are a story-driven species – including the story of our food and where it comes from. When people talk to me at an event, they often say, “I try to eat salmon because I’ve heard it's healthy, but I don't know the story of the fish – where is it grown and is it good for me or not? And is it good for the fish? Is it good for the ocean? I don't know. I don't have the information.” And I think that the most important thing we can do is help people understand the story – the story of the people who captured the fish or who grow the fish. Who are creating innovations within the space?

I travel and speak all over the world on these issues. I go to ocean events, ocean conferences, and symposiums and I hear the same people saying the same things. Year over year, they're saying that we need to do more of it. That to me is the definition of insanity. It’s why we are starting Oceans 2050. It will be about shaping the conversation for oceans around rebuilding marine biodiversity and restoring ocean abundance.

How do you compare wild and farmed seafood?

I stopped eating fish entirely for about 15 or 20 years because the chain of custody is never clear. The practices to this day are not clear to me. I felt a real lack of trust, both on the aquaculture side and on the wild fisheries side. I didn't want to buy any fish and seafood because of what I consider systemic fraud in the industry. It wasn’t that I didn’t enjoy the taste, I just didn't want to be part of the problem. I feel the same about land-based proteins. I only eat meat when it's from a local farm, and I know where it came from. I want to know the farmer, know that the animal had a happy life, and as they say, “had just one bad day.” It is sort of my informal marker.

What persuaded you to start supporting sustainable aquaculture in such an active way?

The pivotal moment came at the Sustainable Ocean Conference in Portugal last autumn. A dear friend, Katherine Bryar, who works for an aquaculture feed company called BioMar, began to help me explore the advances that had been made in sustainable, ethical aquaculture. I knew I had to learn more.

Is there a particular farm or farmer who helped to change your opinion?

I had heard of a third-generation family salmon farmer in the Arctic Circle – Kvarøy Arctic. Alf-Goran Knutsen, the CEO and son-in-law of the founder, was speaking at the conference. I heard the story about the island, the farmers, and all of the forward-thinking intention that they were putting on the water. I was amazed – so amazed, in fact, that when they asked me to try the salmon, after 20 years of eating no fish and seafood, I tried it. I was blown away. It tasted amazing. The more I learned and researched, the more I knew that I could trust this farmer. I heard the story. I heard about the humans who are raising these animals and why he was doing it. It was a fish and a farm that could truly change the industry and aligned with my values.

What aspects of aquaculture are you most sceptical of?

We need to teach the bad actors how to move their practices forward. We need to educate government agencies in charge of the licensing to understand the importance of multi-trophic systems to create more balance in open-ocean net pen farming. We need to focus on enabling conditions for the seaweed aquaculture industry, and aquaculture in general, to really thrive. We urgently need to stop subsidising the bad actors and start investing in innovators and heroes.

How do you see the future of fish and seafood?

It depends on how successful we are and how quickly we respond. I think that we have the potential to fully transform the system as it stands now into something that is really regenerative for our oceans and has a net positive impact for our oceans and for our future. Anything that isn’t net positive at this point has to go. If practices continue to externalise the environmental costs, then we need to boycott them. The threat is real; it’s upon us. It is critical now. Supporting sustainable, ethical aquaculture through regenerative practices and contributive components that grow ingredients vital to our food system is the only way to give our oceans a break. This will allow the rest and recovery needed for this important wild frontier.