© Victor Kaiza

In Dongo village, on Mafia Island, lives a 61-year-old whose smile charms all visitors. His name is Waziri Selemani Mpogo, a former sea cucumber collector and fisherman, who has recently turned into a passionate sea cucumber farmer. Born and raised on the island, Mpogo has been involved in seafood trading since his youth.

“In 1969 a Chinese man called Fong Kai was residing on Mafia Island. He was a famous sea cucumber buyer in our region and our prime motivator into joining the sea cucumber business,” recalls Mpogo.

As a motivated youngster, Mpogo started sea cucumber fishing as soon as it was legalised by The Tanzania Fisheries Act of 1970. Fishing, processing and trading of sea cucumber made Mpogo among the most renowned pioneers of beche de mer.

However, Tanzania’s sea cucumber fishing and trading ban at the turn of the century meant he had to diversify into net seine fishing until 2020, when regulated sea cucumber farming and trading was once again permitted.

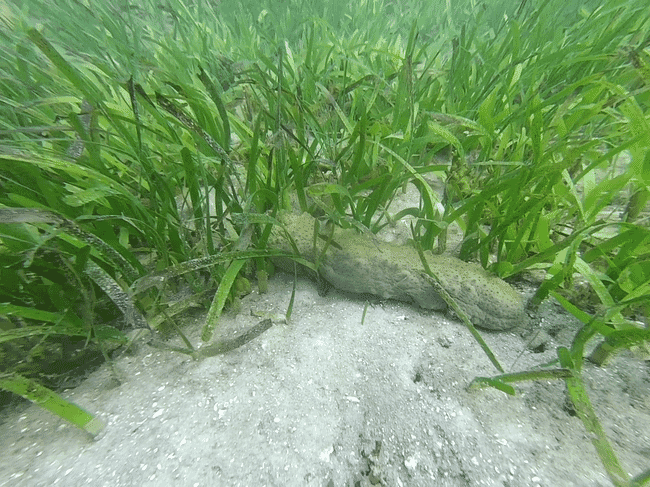

Mpogo was keen to find out more, so visited some of the country’s first sea cucumber farmers, called BMU Kaole, as well as consulting experts from institutions such as the Fisheries Education and Training Agency (FETA) Mikindani Campus. Once he’d gained enough insights he established his own operation on Mafia Island, called Mpogo Ocean Ranching Limited. Having obtained a permit to farm a suitable stretch of coastline from the local beach management unit he demarcated 135 acres of upper subtidal and lower intertidal areas of Mfurumi beach using buoys, divided into three different farming zones, where he produces sandfish (Holothuria scabra) and curryfish (Stichopus herrmanii).

“I opted for a sea ranching system because I like to conserve the environment, I was not impressed by how the pen farming system limits the movement and welfare of sea cucumbers. The stomping of the ground during pen maintenance also disturbs the sea bottom substrate, which in turn causes higher turbidity,” Mpogo explains.

© Victor Kaiza

According to Mpogo, ranching allows the sea cucumbers to graze freely without constant interventions which can cause stress and limit growth and reproduction. He initially stocks 20,000 sea cucumber juveniles obtained from the farm run by BMU Kaole in the lower intertidal zone and then moves these into subsequent zones every 3 months. The sea cucumbers are finally harvested in the upper subtidal zone of the farm, and these fetch US$60 – 120 per dry kilo in Zanzibar.

Sea cucumber farming also helps to support eco-friendly fishing and Mpogo occasionally permits fellow fishers to fish within the farm. In return these fishermen help with the surveillance of the farm by patrolling and informing him about any illicit activity.

“I allow fishers who use eco-friendly fishing gears such as traps, hooks and lines to fish within the farm. Whenever I see a beach seine nearing my farm, I report immediately to the relevant authorities for further action. Beach seining is a destructive practice, dangerous to corals, mudflats and seagrass which harbour fish and other animals, including sea cucumbers,” Mpogo explains.

He aims for his farm to be the epitome of eco-friendly aquaculture through the involvement of the resident coastal community. According to Mpogo, the farm acts as a reservoir for sea cucumbers and other marine animals, ensuring the availability of fish for the village. He also welcomes marine conservationists, researchers and academics to come learn from his success.