-is-one-of-the-pioneers-of-nursery-system-in-Indonesia.jpg?width=650&height=0)

Atjo believes that adopting a nursery phase when farming shrimp can increase annual productivity by reducing the length of grow-out periods and increasing survival rates

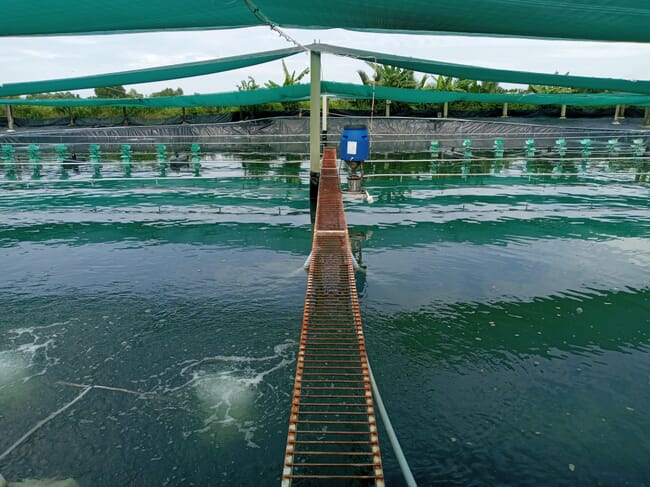

Despite the slow development of multi-phase shrimp farming in Indonesia, it has huge potential, according to Hasanuddin Atjo, a veteran shrimp farmer from Sulawesi. By implementing a nursery phase between the hatchery and grow-out stages at his farm he has increased productivity from 71-100 tonnes to 121-140 tonnes of shrimp per hectare per cycle.

He thinks that the nursery system should be more widely applied in Indonesia, given that it has been successfully developed for intensive farms in Vietnam and Thailand, as well as in more extensive systems in Ecuador. Atjo says that it can increase annual productivity by reducing the length of the grow-out period and increasing the survival rate, due to the highly controlled nursery environment.

Nurseries must mirror the shrimp life cycle

At a recent webinar held by Minapoli, Atjo outlined why the multi-phase system is good for shrimp. As he explained, the shrimp growth cycle resembles a sigmoid curve: starting with slow growth, then fast growth, before slowing down again towards the maturation phase.

In the initial slow growth phase – which takes place in the first 50 days after hatching – the process of cell division in the shrimp's body occurs slowly and they don’t need a large pond. However, nutrition and the environment must be optimised. According to Atjo, larvae should be kept in the hatchery for their first 20 days, before being transferred to a nursery for the next 30.

Atjo says that a multi-phase shrimp farming system can increase productivity, reduce the time to harvest and improve farm management

“The nursery stage ideally takes place indoors. This doesn't need large ponds, due to the slow growth of post-larvae (PL) 1-35 phase, but the shrimp need to be provided with high quality nutrition and excellent water quality parameters,” he says.

According to Atjo, PLs thrive in a relatively low salinity level of around 12 parts per thousand (ppt). This level of salinity can also inhibit growth of bacteria such as Vibrio and Atjo thinks that bacterial disease outbreaks in the ponds can be triggered by higher salinity.

After the first slow growth phase, shrimp start to grow faster, as cell division increases significantly. Atjo argues that this is the best time to transfer shrimp into larger ponds. In addition, the bigger juveniles that are obtained from the nursery can adapt well in fluctuating environments, although they will perform better if their environment and nutrition are optimised. Atjo explains that the grow-out phase, after they have been transferred from the nursery, should be done for 70-90 days.

"In the slow growth phase some of the energy from feed is used in the maturation of reproductive organs, so that the growth rate decreases," he adds.

Atjo says that although the feed costs will be higher in this system, farm management and evaluation will improve significantly

Optimising nutrition at a critical phase

The other reason why the nursery system is worth considering is because it allows for the optimisation of shrimp nutrition. In the single-step grow-out system that is more commonly used today, farmers usually feed the shrimp using the blind feeding method, based on the number of PLs stocked into the pond. This is designed to introduce and adapt shrimp to factory feed for about 30 days, using a volume of powdered feed that is related to the number of shrimp stocked. In this phase, natural phytoplankton, which is generated by adding fertiliser to the water, is also available as feed. At the end of the blind feeding programme, farmers will calculate the next feeding programme based on the current biomass, for example providing feed equating to 10 percent of the biomass per day.

Atjo notes that, with the nursery system, although the feed cost will be higher, farm management and evaluation will be much better, as the smaller nursery ponds make it easier to assess the shrimp and to control the conditions. He recommends continuing feeding shrimp with artemia, as previously done in the hatchery, for three days and combining these with formulated feed with a high protein content (40-50 percent) and also high water stability. After three days, shrimp should be weaned on to formulated feed.

For the first three days he suggests that farmers daily provide 454 grams of artemia for every 1 million PL. As well as helping the transition process before being given factory feed, artemia contain glycogen and omega 3 fatty acids, which are good for shrimp growth and immunity. Meanwhile the volume of formulated feed should be 10 - 20 percent of the estimated shrimp biomass in the system. Based on his experience, feeding eight times a day works well. However, he adds that using an auto-feeder, which can provide feed more often, might improve results further.

Smaller and round tanks can suppress EHP outbreaks since they reduce effluent build up and provide a central drain © MMAF

Reducing the risk of EHP

In Asia, Vietnam is a good example of the multi-phase system being widely used – with many farms having nurseries with relatively small, circular ponds. The founder of Aquaculture 101, David Kawahigashi, confirms that roughly 40 percent of shrimp farmers in Vietnam typically use grow-out ponds under 1,000 m2.

“The trend, as we have seen over the years, is to opt for smaller grow-out areas. Whereas in the old days we used to produce shrimp in half hectare ponds, over time the ponds got smaller and smaller and now many farmers use 500-800 m2 tanks,” he says.

Based on his experience in developing round pond systems for nurseries, he says that the system has many advantages. One of them is making it easier to centralise the organic effluent in the central drain or shrimp toilet and then discharge it into the sludge reservoir. He argues that this helps to suppress Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP), as he thinks that an excess of organic compounds in the ponds, which is reflected by increased water turbidity, is the trigger for the emergence and outbreak of EHP.

“The Vietnamese say that EHP microsporidian spores are sticky and they attach to the biofloc and other substrates and become ingested by the shrimp. And so, a pure biofloc system is no longer the accepted practice in Vietnam. They go more for the low turbidity, efficient cleaning of the tanks to stay ahead of the EHP spores, because there was a positive correlation between the build-up of organic matter and sediments and the concentration of EHP spores,” Kawahigashi explains.

To make sure the water quality is always good, Vietnamese farmers also apply a recirculation system and spare more land for water treatments. Within 24 hours, the water in the pond should fully recirculate. While the reduction in shrimp farming area is offset by the increased carrying capacity of the farming ponds. He says that the average productivity of this system can reach 8 kg per m2.

“There's a much greater area dedicated to water settling and treatment than for grow-out. But it pays off because the amount of biomass produced and the improved water quality,” Kawahigash says.

-gets-souvenir-from-CEO-Minapoli-Rully-Setya-Purnama-(right).jpeg?width=650&height=0)

David Kawahigashi (left) receiving an award from CEO Minapoli Rully Setya Purnama (right) after giving speech about multiphase system to Indonesian farmers in Vietnam

According to him, the nursery system is very feasible for use in Indonesia. This is supported by the relatively good water quality in Indonesia, which means that they might not need to use as much of their farms for water treatment as they do in Vietnam.