“We got it wrong with fishmeal,” Nikolik admits. “Back in November we expected soft prices due to the large quota (2.8 million tonnes) that had been set for Peruvian anchovies and due to the pile up of fishmeal inventories in China that were being caused by the reduced demand from the pig sector due to African swine fever.

“However, since then the anchovy catch looks likely to drop to closer to 1 million tonnes, with early closures looking likely and China’s aquaculture sector has used up the fishmeal inventory, meaning that fishmeal prices are going to be fairly strong after all.”

Despite a return to comparatively normal fishmeal prices, the seafood analyst believes that the fish farming sector will not be hit hard.

“It shouldn’t affect the aquaculture sector too much – in part due to the comparatively low inclusion rates of fishmeal in contemporary feeds and in part due to the fact that the price is recovering to normal levels. It’s also good news for alternative protein producers, who struggle to compete when fishmeal prices are too low,” he says.

Salmon growth set to slow

Nikolik also notes that the salmon sector threw up a few surprises last year.

“We had expected a decline in production but it turned out to be a strong growth year, especially in Norway – where there were even some double-digit growth months over the summer,” he reflects.

And the causes of the increase have also surprised him.

“We thought that any growth would be driven largely by an increase in harvest weights, but the sector actually had lower harvest weights than in 2018, especially in Q3. Despite this Norway still managed to increase production by around 6 percent – largely based on the increase in the numbers of fish being stocked, rather than premature harvesting.”

“It turned out to be a good year in Chile too, with production growing by around 5 percent – largely in line with our forecast.” Nikolik adds.

Despite this he sees growth – both in Chile and globally – slowing during 2020 and beyond.

“Chile’s strong start to 2019 was undermined by increasing issues with lice as the year went on and we are wondering whether the country is going to go through an experience similar to what happened in Norway four or five years ago, when lice started to become resistant to a range of medication,” he explains.

“As a result I think that the growth of the global salmon sector looks likely to slow down a bit, with Norway likely to increase production by 3-5 percent, both in 2020 and 2021; while Chilean growth is likely to be in the region of 0-3 percent due to potentially lower harvest weights and legislative limits.”

Nikolik therefore forecasts prices to remain strong.

“On balance if the sector grows by 3-5 percent globally then we can expect strong prices to continue. 2019 saw some seasonality of prices – with the spot price dropping to under 40 kroner per kilo for the first time in four years in the summer – but we expect the 2020 prices to average around 60 kroner, which seems to be the new normal,” he notes.

Nikolik is also keeping an eye out for emerging trends – not least the rise of salmon produced in RAS in the likes of the US, China and Japan, as well as those offshore salmon farming projects that are nearing commercial production in Norway and China.

“We’re entering a 2-3 year period in which land-based and offshore farming systems will deliver a new supply source and the performance of these ventures in 2020 will be pivotal in deciding how much capital goes into similar projects, and it will be interesting to see whether salmon produced in these systems will be able to achieve premium prices,” Niklolik explains.

Shrimp: "the avacodo of seafood"?

The shrimp sector also sprang a few surprises during 2019, as Nikolik notes.

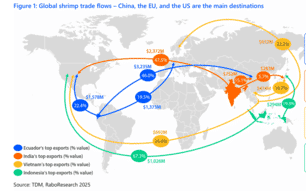

“The industry was braced for a drop in supply in the first half of 2019 but this only happened in India in the end, while the second half of the year was characterised by a bullish outlook in supply, especially in Ecuador [exports grew by over 25 percent year on year]. Even in India the large growth in shrimp production in H2 led to an overall annual increase of 3-5 percent compared to 2018,” he says.

And he points out that the sector proved to be something of an economic anomaly.

“In most industries a decrease in prices will lead to a decrease in growth, but in shrimp growth has continued – in Asia as well as Ecuador – despite the decrease in prices that has occurred since 2018. Although some farmers have left the sector those remaining have improved their performance and the cost of production is still low enough to allow them to grow,” Nikolik says.

Looking ahead he is happy to make some predictions, but notes that it’s not an easy sector to forecast.

“The shrimp sector is notoriously difficult to predict due to the large number of variables and the short cycles involved in shrimp production. But we expect 2020 to be yet another year of growth, although this growth is likely to be more balanced and we’re expecting 10-15 percent growth in Ecuador,” he says.

In order to remain profitable, Nikolik believes that establishing the right marketing strategy is vital.

“The good supply momentum hasn’t been matched by the growth of strong marketing. This is the year to make shrimp the avocado of seafood – marketing is needed to prevent it becoming another pangasius or tilapia. The shrimp industry must learn from the salmon sector and keep the product exclusive by bolstering demand – the whole sector must connect with retailers and consumers,” Nikolk argues.

“I think it will be a very interesting year for shrimp farmers and a good year for consumers of shrimp,” he concludes.