After many decades of subsistence and small-scale fish farming in Nigeria, Ade Alakija catalysed commercial catfish farming in the country with his focus on production of high-quality fingerlings and use of the highest quality feeds. By establishing intensive large-scale hatcheries, using the best feeds – in pellet sizes responding to all stages of growth – he set the stage for rapid growth of the private sector catfish industry in Nigeria from the 1990s. Sadly, Ade passed on in 2009 at the age of 44. This article seeks to trace his life and his pioneering contributions to aquaculture development across Nigeria and the wider African continent.

Ade was born in 1965 in Ibadan and went to nearby All Saints primary school. From a young age he always liked learning about nature, animals and fish. His favourite school picture book A Fish Out of Water by Helen Palmer, which he kept all his life, very prophetically for Ade, included words about how the little fish didn’t like to be fed too much.

From an early age, Ade’s family provided him with opportunities which channeled him towards striking out on an independent path leading towards aquaculture. At the age of 11 he was sent to Malvern College, in the English Midlands – the Malvern hills being a scenic landmark, appreciated for nature and wildlife, as well as its famous spring water. At school Ade was a natural at many sports – primarily rugby, hockey and cricket – following on from his fathers’ footsteps, who had represented Nigeria in cricket in the 1950s and 60s. He was also passionate about biology and wanted to understand more about rivers and fish from an early age. This further developed when his mother bought a house on the banks of the nearby River Wye, close to Hereford – at that time a small market town in the so called “golden valley”, famous in the books of CS Lewis and Kasuo Ishuguro.

The teenage Ade spent his long summer holidays roaming the river fishing and learning about birds, animals, fish, plants and how they interacted with each other. In those early days he also noted how human activity was beginning to encroach on the river, commercialising agriculture, industry and new factories, new residential housing etc. Something that is now causing significant issues for this famous river.

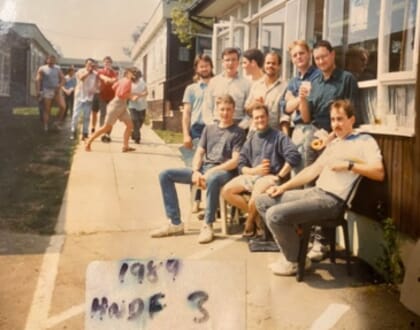

In 1982, aged 17, Ade went to Plymouth Polytechnic, to do a course in fisheries. However, he quickly found it overly-academic, almost entirely lecture-based, with little hands-on practical demonstration. He therefore, quite boldly at that time for an 18-year-old, decided to move to one of England’s most famous agricultural vocational colleges, Sparsholt College, which was running joint fisheries and aquaculture courses, diploma and certificate level, with up to three years of studies.

At that time aquaculture in the UK was at the early stages of developing commercially, particularly in Scotland with the growth of commercial salmon cage culture, while the trout farming sector was beginning to grow around the chalk stream rivers Test and Avon, within a stone’s throw of the college.

Ade and his fellow students voraciously learnt from their hands-on visits to the many fish farms and hatcheries springing up around Sparsholt, and the college also developed its own facilities – including a small fish farm and hatchery, plus in later years, warm water tank facilities for tilapia, catfish and carps. Ade was in his element in those three years – Sparsholt College still runs such courses and many others today up to BSc level, with many of its former alumni going on to make significant hands-on contributions to aquaculture development, not just across the UK but, as in Ade’s case, internationally.

One of Ade’s classmates, Mike Gubbins, who is now a senior fish diseases inspector at the government’s CEFAS fish diseases laboratory in Weymouth, remembers Ade to be “an exceptional talented and very driven person, but also at the same time very personable and charming, even at that young age, quite different from most of his classmates”.

He apparently made friends with all, but particularly with Graham, the other African on the course from Malawi. Ade spent his college working internship at Kingston Polytechnic, outside London, where at that time Professor Carmelo Agius was developing a warmwater tilapia catfish research facility in a converted church building. His final thesis was on tilapia and he left Sparsholt with a distinction and the award for best student in his year, as well as prizes for sports, including hockey. Around that time he also met his wife-to-be, Polly, in Malvern – a partnership which was to produce and bring up four children, and flourish throughout their days.

After completing college, his father was keen for Ade to go back to the family business in Nigeria – an established import/export company for electronics, industrial machinery and engine parts. However, Ade had other ideas and wrote with envelope and stamp pre-internet days to Professor Tom Lovell at Auburn University in the US. Tom advised him to come and visit fish farms in Mississippi and Alabama, where he spent time like a sponge, soaking up as much practical information as he could from the many commercial catfish farmers he visited, as well as from academics, most notably at Auburn.

This trip was followed by similar learning trips, including to Wageningen University in Holland. As the young Ade knew, Wageningen at that time was developing an applied research programme on the African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), which was launched in the 1970s and led to the “Dutch strain” of clarias, which was later exported to Nigeria. Ade believed this species was ideally suited for not just farming in Nigeria but also for selling, since he knew how much Nigerians cherished eating catfish. He was also aware of the huge unfilled market demand for catfish, in a rapidly urbanising population of 140 million, and Nigeria’s status as the most populous country in Africa.

In 1989 Ade returned to Nigeria to set up his first earthen pond-based catfish farm in Oyo State. He established his company, Durante Fish Industries, in Ibadan, in abandoned warehouses adjacent to land that had a good water supply, appropriate soils and access to nearby consumer markets. Those early days were both a time of great experimentation and also huge risk for Ade, as most of Nigerian catfish farms were just a few ponds as part of wider farming activities. Seed fingerlings were collected from the wild and fish were fed local agricultural byproducts. Many were hobby farmers, keeping some large catfish to show friends and visitors. At that time no one in Nigeria had made significant investments in large-scale catfish farming.

With no commercially produced formulated feeds available, Ade and his staff found themselves preoccupied with searching for feeds, something Ade found frustrating since it meant having less time on the farm with the fish. Crude feeds available included maggots and termites, as well as slaughterhouse and canteen waste.

Not only was Ade struggling to find feeds, he was also spending much time collecting catfish fingerlings from the wild. Quickly he realised that a hatchery was essential if his new company was going to survive, so the first rudimentary catfish hatchery was built on the site. The hatchery’s development evolved from what he’d learnt at Sparsholt, Kingston Poly then his visits to Auburn and Wageningen, as well as many mistakes and lessons learnt along the way. After much trial and error, late nights and early mornings, the hatchery began to produce significant numbers of juveniles, while Ade began to develop broodstock with good growth traits and body conformation. Later, he benefited from importing the Dutch “improved” African catfish from the Netherlands.

Ade later reminisced he owed the success of the company and all that followed to two people. The first, Hilary Sydenham, a family friend who regularly encouraged him with robust advice and sound business management skills. The second being Willy Fleuren, who he met on his first visit to Wageningen and would remain his lifetime business colleague and friend.

They were built inside abandoned warehouse in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Willy formed his own company, Fleuren Nooijen, based in the Netherlands. This developed the designs, procedures, management and financial viability for commercial catfish farming which were piloted and then further developed by Ade. Willy recalls when he first arrived in Lagos as a consultant to work with Durante Ade offering Willy a cash advance in the airport carpark to show his commitment and seriousness. It is interesting that both Ade and Willy always focused on Clarias catfish, rather than tilapias. This was in response to a number of factors. Firstly, the huge demand among Nigerians for catfish, which were consumed widely in popular “Buka” restaurants, where workers enjoyed freshly made fish pepper (pepe) soup at the end of the day. Secondly, they both knew of the hardiness of the species, and its relatively few disease problems. With an accessory air-breathing organ, catfish were also easily handled and transported to markets where they were sold live in tubs with little water or as smoked fish – this was ideal for Nigerian consumers, most of whom at that time lacked refrigerators. Catfish could also be stocked at far higher densities than tilapias – often over twice the density in terms of final harvest biomass.

Ade learned many lessons from his efforts at his first earthen pond farm. He quickly realised his problem wasn’t so much how to grow the fish, but how to actually keep them. Theft was a huge problem and, in those first years, when harvest time came along, Ade found there were almost always significantly fewer fish at harvest than had originally been stocked. This made him improve the site security fencing and the staff management, and also realise that catfish could not be just left in a pond for six months, fed and then harvested. Ade knew he needed to improve management to greatly increase survival of fish to the end of the production cycle.

If the company was going to make a reasonable profit, then handling fish at stocking, pond feeding, stock control, sampling and record-keeping had to be far better. Regular sampling and test weighing of fish for each pond was introduced on a monthly basis, any mortalities were carefully recorded and, to estimate pond biomass, average test weights were calculated at the end of each month. From this, approximate quantities of feed required for particular pond biomasses were calculated and feeding was increased accordingly as fish gained weight. From these figures Ade also realised the critical importance of knowing on monthly basis the feed conversion ratios (FCRs) for each of his ponds, and how much difference it made to the bottom line of his profits, something he taught others for the rest of his life. Feeds proved to be the largest percentage of his daily costs.

From Ade’s practical experiences, he learned that quality fish seed and feeds were the key to achieving good fish production and profit. Thus, a focus on selected broodstock was necessary to have fast growing fish which were able to assimilate quality feeds in the most efficient manner, with FCRs offering the least cost per kilogram of weight gain. These two realizations were put to use by Ade’s Dutch connections, Wageningen and Willy Floren, as together they provided solutions to success in catfish farming.

In 2005 Ade worked with Willy and others to set up and produce some of the first commercial formulated feed for catfish in Nigeria - Durante Fish Feeds – in the suburbs of Ibadan. Once up and running, Durante produced up to 500 tonnes per month in different sized extruded pellets. Again, he found this took up increasing amounts of his time, keeping him away from managing the farm, something in later years he said he regretted.

Ade succeeded in intensifying catfish production, allowing them to feed on demand.

Nonetheless, access to quality feed was an essential prerequisite for sustainable growth in the value chain in a country new to aquaculture development. Later, Ade’s business, Durante Fish Industries, supplied feed in Nigeria from the Dutch feed company Coppens, in a variety of extruded pelleted sizes, responding to the requirements of each growth stage of catfish. Then towards 2008-09 Durante became involved with Skretting, especially in relation to their concentrates sales into the Nigerian market.

By then Ade’s business had become a vertically integrated supplier of quality fingerlings, quality fish feeds and equipment needed to establish intensive recirculating systems for hatchery operations. It was operated out of abandoned warehouses in Ibadan.

The hatchery operation used typical induced spawning techniques with selected broodstock and intensive rearing of fry to fingerlings for grow-out. High survival rates were obtained through proper handling and grading of fish, along with feeding the right sized pellets at all stages of growth. Grading of fingerlings was essential, since faster growing fish preyed on slower growing cohorts. Feeding was stimulated by keeping the hatchery in semi-darkness, in consideration of the nocturnal feeding habits of catfish. Such husbandry techniques yielded high survival rates and rapid gains in weight during the early growth stage.

Later these techniques provided up to half a million fingerlings per month. Durante Fish Industries captured the market with its selected broodstock, high quality feeds and intensive rearing methods, all promoted as a package to the growing number of commercial fish farmers.

The Durante package was an economic success which catalysed a number of fish farmers to diversify into specialisations including hatcheries, feed production, grow-out and processing. High demand for smoked fish expanded the value chain and provided jobs for women and youth. A fish marketing study from 2006 revealed some 30,000 fish processing jobs were created by the popular Buka restaurants. Later more employment was created as the fast-food industry added catfish to their takeaway menus.

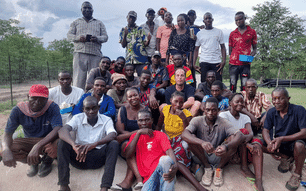

Ade took much pride in helping new fish farmers through training programmes and mentoring as part of his collaborative efforts with different projects. Furthermore, extensive youth mobilisation programmes were underway, which had training workshops for increased youth employment. In 2010 an Aquaculture Buyers Guide was produced, showcasing this situation.

Once Durante was on its way with hatchery juveniles and formulated feed production, Ade wished to address continuing issues with theft of pond stock and farm management eating in to profits. Together with Willy and following on from the expanding research on recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) for the grow-out of catfish in the Netherlands, they designed and built one of the first truly RAS catfish grow-out sites. This was located inside a warehouse, in the Challenge Road area of Ibadan, where key water quality and management procedures could be carried out and controlled routinely.

Within their first two production cycles they could see significantly higher survival rates. This RAS site in its first year produced 150-200 tonnes and the two men went on to design and build a second improved version, with production of up to 300 tonnes per annum and harvest biomass at around 120 kg per cubic metre. At that time there were around 20 staff employed in the hatchery and grow-out parts of the company.

Whilst the RAS sites had been successful, both Ade and Willy were aware of the increasing production costs involved in using such energy-intensive and high risk grow-out systems. Local electricity supplies were notoriously unreliable and, in spite of backup diesel generators, there was always an element of risk in holding such high densities and biomasses of fish. Nevertheless, the increased risk of losing tonnes of fish from the frequent blackouts brought about a refined operation, combining hatchery operations in the warehouse with more use of earthen ponds for grow-out.

Ade, now armed with years of experience, went back to his original pond site at Oyu to refine and develop its production model so that it could be more competitive on production cost per kg. With much improved security and daily farm management, less risk was involved, producing fish at lower, more affordable cost per kg.

This pond system was also more easily replicated by the growing numbers of Nigerians who were attracted into catfish farming as a business.

“At that time electricity diesel and energy costs were only going one way (up); therefore, it made sense for us to go back to ponds and also peri-urban concrete tanks with intermittent water exchange and look to fine-tune and develop production systems that others could both afford and follow. We continued with RAS in the hatchery for juvenile production,” Willy explains.

Particularly in his later years, Ade was a driver of the commercial fish farming industry in Nigeria, carrying out training programmes with different groups, as well as following up with fish farm operators who were using equipment he’d sold them. Between Willy and Ade they designed and built between 15-20 farms for others. Their approach of embedded extension provided effective practical support, based on real-life experience – things that most government extension workers and overseas donor-funded projects lacked.

It is important to note that Ade’s support to hundreds of small-scale fish farmers helped to bring about a truly commercial aquaculture industry in Nigeria. Ade took many risks in developing techniques for intensive hatchery management for massive production of fast-growing fingerlings as well as production of nutritionally balanced quality fish feeds. His vision and perseverance in leading the private sector fish farming industry places him as a true pioneer of Nigeria’s aquaculture industry.

With more than 4,000 fish farmers now operational in Nigeria, Ade’s legacy has served as an inspiration to many who now benefit from improved broodstock, access to hatcheries and a very competitive fish feed market. Demand for catfish continues to grow to feed the country’s increasingly peri-urban 200 million population. Techniques for raising catfish are exported from Nigeria to countries throughout Africa, where expanding value chains have created thousands of jobs and expanded markets.

Of course, many factors have joined together to make the African catfish industry grow, but Ade clearly inspired and impacted many across the continent. While he is sadly missed, his legacy lives on for thousands of young Africans to follow.

We wish to thank Polly Alakija, Willy Fleurens, Sparsholt College, Mike Gubbins and Randy Brummett for their help and time in producing this article.