I grew up recreational fishing in New York Harbor with my family. Seeing so many fish stocks slip into decline in the mid-Atlantic, I realised that I wanted my life’s work to focus on helping fish stocks recover and create a better future for our ocean and fishing communities.

© Robert Jones

The first job I took out of college was as a commercial fisheries observer for the US government, sampling and estimating fisheries catch on boats from Massachusetts to North Carolina.

At this point, I will admit that I had a pretty negative opinion of aquaculture. I accepted as fact news stories that focused solely on the negative impacts. When I heard the word “aquaculture” I immediately thought of mangrove destruction in Asia and fish raised in unhealthy conditions with too many chemicals. I was the one telling my friends and family not to eat farmed seafood.

But one experience, ironically as a fisheries observer, changed the way I viewed the environmental and social potential for aquaculture as a benefit for both coastal communities and ocean conservation.

“Somehow you ended up here with me on George’s Bank in the middle of October,” said Joao, the captain of an 80-foot New Bedford dragger. A lit cigarette hung from his mouth as he gripped the helm - the steel hull of his vessel pounded through raging fifteen-foot breaking waves. “Are you having fun yet?” he asked me with a wry smile.

© Robert Jones

We were over 150 nautical miles offshore of Massachusetts, pushing towards the international border between the US and Canada, bottom trawling for groundfish. By all accounts, it had been a tough trip. A nor’easter had ploughed its way towards us, requiring us to steam for cover and moor up behind Nantucket for two long days. When we finally made it back to the fishing grounds, the fishing was slow and a lot of what the crew did catch had to go back. I watched thousands of pounds of Atlantic cod bycatch have to be thrown back dead.

After more than 11 days at sea, we made our way back to the harbour. The iconic gloomy New England pea soup fog coated New Bedford harbour and the lighthouse emerged suddenly off the bow. As I stood on deck, I saw the crew climb down from the wheelhouse after a meeting with the captain.

I heard a door slam in the cabin over the baritone hum of the diesel engine. I entered the cabin and saw the crew, sitting around the galley table looking dejected. They had just received word from the captain about their expected wages – a mere few hundred dollars for over a week’s worth of backbreaking labour. One crewman looked me in the eye and said: “I’m not sure what I’m going to do now. I don’t even know if I’ll be able to pay my rent.”

Something was wrong with this picture. It was clear we weren’t meeting our biological and environmental objectives for the fishery – the amount of seafood produced from the fishery was less than it should be, while non-targeted fish stocks continued being overfished. However, on top of this, we weren’t meeting the economic needs of coastal communities.

What was the solution? It was at that moment that I began thinking outside the box of fisheries management and began to consider for the first time the potential for aquaculture.

Wild fisheries continue to be an important part of global seafood supply, jobs and coastal communities, as well as provide a critical protein supply for millions. We have an obligation to ensure wild fisheries management is successful for the benefit of our ocean and the people that depend upon it.

But I started to consider: could aquaculture, when done well and alongside improved fisheries management, be part of a winning solution to provide sustainably produced seafood and create essential jobs in coastal communities like the ones I had come to know as a fisheries observer? Surely not in all cases, I thought – but I began to explore when aquaculture could be part of the solution rather than part of the problem.

I started doing my own research in between trips at sea. I quickly realised that I had only understood some aspects of the global aquaculture industry and its impacts on our planet. I learned that there were many ways of producing seafood through aquaculture, that impacts varied, and that aquaculture is one of the most resource-efficient means of producing animal protein. That aquaculture, when localised impacts are reduced, could be one of the best ways of producing food for a growing planet.

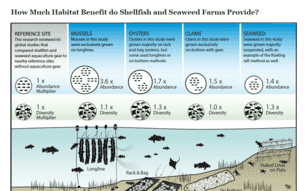

With restorative shellfish and seaweed species, I recognised a major business opportunity that could create environmental and social good. These species can create food with near-zero inputs, while also providing positive ecological benefits to recover and restore coastal environments that have been impaired by the habitat degradation and coastal eutrophication. As lower tech and capital intensity endeavours, these production types can have lower financial and knowledge barriers for coastal communities.

This trip in the Northeast ten years ago ignited a passion and mission that I carry with me today at The Nature Conservancy. While I’ve shifted my work from wild fisheries management to sustainable aquaculture, my goals remain the same – to create a better future for both our ocean and coastal communities.