Can you briefly describe your aquaculture career?

Right after finishing my masters’ degree in the early 90s, I jumped into a three-year sea scallop bottom culture project at Dalhousie University, Halifax. The Ocean Production Enhancement Network (OPEN) funded program focused on basic oceanographic and biological research, targeting sea scallops and cod. With a background in photography and SCUBA diving experience, I was hired to use an underwater video camera to record the ocean bottom along transect lines – capturing our seeded scallops, wild scallops and predators. Diving four to five hours a day in the fall and winter was mind-numbing, but a lot more fun than the follow-up: five days of analysing video footage in the lab…manually. And manually gluing two bee-tags on about a third of our 10,000 juvenile seed scallops ranked right up there with the video analysis.

As video production technology was rapidly pushing towards a completely digital workflow, I remained in the field specialising in underwater filming and post-production projects that focused on seafood and aquaculture research. And my mission has been to see how far we can press automated vision technology into a multi-tasking marine research tool.

What is MarineCanary and where did the idea come from?

Like a canary in a coal mine, the MarineCanary (MC) is an early warning system designed to detect waterborne issues like hazardous algal blooms, pollutants, high water temperatures and hypoxic conditions, before they hurt marine life. Each unit is created as a stand-alone, drop-and-go system that is suspended in the water column between its float and anchor mooring system. Within the MC unit lives a set of mussels. When a significant number of them close their shells, a warning is sent to the user’s mobile device.

The original MC unit was designed almost 25 years ago by IntegraSEE co-founder, Ulrich Lobsiger, and was based on recording and analysing live mussel behaviour using timelapse film technology, but – as machine learning, deep learning and AI weren’t readily available – there wasn’t a lot of incentive to commercialise a product that required manual image processing.

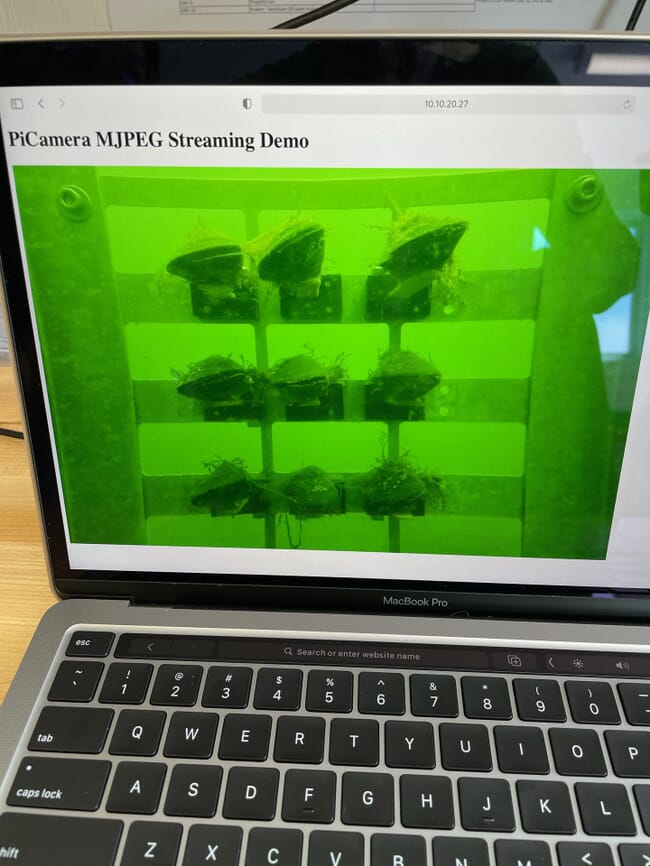

That all changed last July when Karan Kharecha, our computer science team member, and I, deployed our first prototype in Halifax Harbour on COVE Ocean’s Stella Maris platform. The prototype is composed of a metal frame with nine mussels secured with popsicle sticks on one side, and an underwater enclosure containing a fully digital video recording system on the other. At this time, data and power are transferred via Stella Maris’ umbilical to shore, but in future, the MC system will be completely self-reliant to capture and process images. The system only records during daylight hours, but Ocean Tech students from the local community college, NSCC, are developing an infrared lighting array that will be triggered by a photocell to turn on. We’re also investigating the use of UV light to prevent fouling on the camera end of the enclosure.

Unlike Mussel Watch programs across the world, which monitor pollutants by analysing mussel tissue samples, or mussel valve-gape research that attaches magnetic or accelerometer-based sensors to the mussel’s shells, the software Karan is developing automatically analyses video footage and ranks mussel behaviour: valve-gape, feeding, respiration and general behaviour.

What impact will it have once it’s operational?

Functionally, an aquaculture operator can place a MC system up-stream of their site and be warned of any pending water quality issues via mobile connectivity. As our technology matures, the final software product will integrate on-site sensor and ocean big data, making it “Predaptive”: capable of forecasting environmental events and helping develop management best practices. MarineCanary has broad marine and freshwater market applications, but we’re currently focusing on shellfish and finfish farming.

What feedback have you had from the aquaculture sector to date?

From our research, the finfish sector is the bigger play for our product as an early warning system because of the global volume and value of finfish versus shellfish, and that climate change not only impacts sea temperatures and oxygen levels, but also drives sea lice, diseases and hazardous algal blooms. One recent business report estimates that global production forecasts may be overestimated by 6-8 percent because of climate change, and another estimates the cost of environmental-related moralities in the tens-of-billions. Toxic algae events are on the rise globally and can wipe out millions of fish in days, which in turn has fed into anti-farming messaging. Mussels, however, are adapted to help better manage these risks - they are essentially multi-sensor platforms in a shell that are on the job 24/7.

Meanwhile talks with Canadian shellfish growers revealed two key challenges: basic biological knowledge gaps and the lack of social acceptance, just like salmon growers. As most Canadian mussel and oyster growers are dependent on wild spat, mussels or oysters can be used in our system to help predict and forecast peak spawning periods and fouling settlement. Our system could also monitor product performance as farmers selectively breed for more climate resistant animals; better understand and prevent mussel “fall-off”; and help expedite reopening sites after storm events, based on water quality.

Like many coastal nations, Canada would like to significantly increase aquaculture production. However, as seen in BC this year, social acceptability, not scientific evidence, drastically reset Atlantic salmon production policy. On Canada’s east coast, the lack of working communities, not-in-my-backyard and the influence of anti-fish farming campaigns has stagnated shellfish growth, particularly in Nova Scotia. By providing an animal’s perspective, and video evidence, our mussel sentinels can provide verifiable, auditable third-party water monitoring for sites being considered for production, just starting production, or are already active: addressing social acceptability by monitoring environmental and animal welfare, and thereby increasing public awareness and consumer confidence.

What’s your business plan?

We’ve been actively securing pilot projects with shellfish and finfish growers in Atlantic Canada, as it’s our plan to commercialise MarineCanary globally. Shellfish pilots will be extremely valuable in accelerating our understanding of how mussel sentinels function over an entire season and with age. That being said, we’re not going to wait to collect footage from salmon growers and will be testing the value of multiple integrated MC systems: up-stream, within pens and around pens. Lastly, our business team – led by Mike Hayes and Mike Cyr – is working on turning pilot projects and early adopters into long-term paying customers by helping farmers develop their own compelling message so that they’ll gladly sign up – a frictionless experience from pilot, or early adopter, to customer.

What challenges do you still need to overcome?

As a professional photographer I’m used to handling some very expensive camera gear but developing our image capture system has essentially been off-the-shelf inexpensive. The challenge will be to see how far we can push our Raspberry Pi-based system and develop a completely remote drop-and-go system that can generate real-time alarms.

Software development, image processing, skilled personnel and funding on the other hand are going to be our biggest challenges over the next year. But, we’re very excited and encouraged by the protype’s performance during its first two months underwater on Stella Maris. During the next three-month deployment, we’ll be working to integrate our images with data from the other dozen-plus sensors on the platform.

What’s your ultimate ambition in the aquaculture sector?

It’s been very exciting reviewing our first two months of footage – nine times during this period, all nine mussels closed at once, indicating there was something afoot. Just like what Poznan, Poland’s water treatment plant looks for from its wired mussels (valve-gape sensors). When four of their mussels close at the same time, the city’s water supply is shut off.

Remarkably, mussels provide a more relatable estimation of overall water quality than expensive one-off laboratory tests. And our mission at IntegraSEE is to create the technology that unleashes marine and freshwater resources responsibly and sustainably.