The study found that the production of feed used to nourish farmed fish is one of the most significant contributors to the industry’s GHG emissions © Chen WS

Aquaculture’s expansion has yielded multiple benefits – the provision of high-quality animal protein for people across the globe being among them. However, the industry’s growth is accompanied by a corresponding rise in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which are a major contributor to global warming and climate change.

As China is a world leader in aquaculture cultivation, a research group led by the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, conducted a study to discover the GHG emission levels produced by the country’s aquaculture sector. Their results, published in the KeAi journal Water Biology and Security, show that the production of feed used to nourish the fish is one of the most significant contributors to the industry’s GHG emissions.

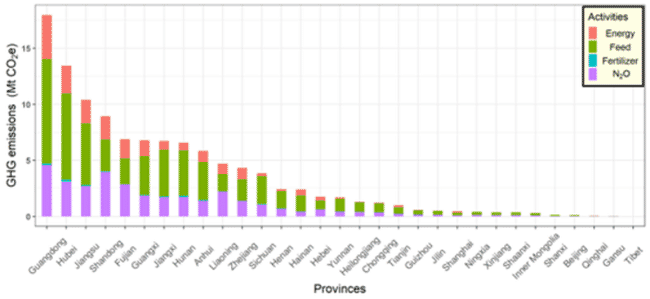

According to Prof Jun Xu, group leader of the study, the team began by measuring the GHG emissions of four key aquaculture processes. They considered energy use – like the energy used to pump water, provide lighting and power vehicles on aquaculture farms. They also looked at nitrous oxide generated by the animals’ excreta and excess food in the water, and they studied the production of synthetic fertiliser applied to increase productivity. The fourth element they considered was the manufacture of feed, raw materials such as soybean meal, wheat and fishmeal, and the emissions from their production, processing and transport. They then measured the carbon footprint of each of these processes over the past 10 years, splitting the results by region and by nine major fish species groups.

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and the percentage of the four activities in each of the 31 provinces © Conjun Xu Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Prof Xu notes, “the results show that the production of feed materials contributed most to the GHG emissions. Spatial analysis showed that Guangdong, Hubei, Jiangsu and Shandong had the highest GHG emissions of all the 31 studied provinces, accounting for approximately 46 percent of all emissions.”

The team also found a significant positive correlation between regional gross domestic product (GDP) and GHG emissions in every province (> 0.6). Prof. Xu explains, “the aquaculture and mariculture industries have developed rapidly in China, and increased production is often accompanied by higher regional GDP. Rapid economic and social development leads to higher levels of consumer demand for products from both aquaculture and mariculture. This in turn drives expansion of these industries in provinces with a higher regional GDP.”

The team’s results also show that China’s aquaculture had a lower emission intensity (2.7) than the global value (3.3) published by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation. They believe this is due to China’s higher percentage of bivalve production. Bivalves usually source their nutrients directly from the water, removing the need for manufactured feed.

Prof Xu says, “studies on quantification of GHG emissions from aquaculture are scarce in China. Our study reveals, for the first time, the relationship between the relative production by species composition and spatial distribution. Importantly, it provides the scientific basis for the reduction of GHG emissions within a broader context of expanding aquaculture in the future. But it’s clear that more work is needed to better understand the mechanism of the process.”

He adds, “we suggest that local managers and governments adjust the relative proportion of species-group production and change the source of energy use to reduce the industry’s carbon footprint. We believe that this work has implications for the future of China’s aquaculture industry, and aquaculture in countries facing similar issues, such as Indonesia and Bangladesh.”