According to FAO (2020), Indonesia produced 9.3 million tonnes of seaweed in 2018 (29 percent of the global total) – capitalising on the country's 99,000 km coastline. This makes it second only to China, which produced 18.6 tonnes, in the global seaweed rankings.

However, Indonesia’s seaweed export value is below that of South Korea, whose production is far lower. In 2019, the export value of Indonesian seaweed was only $218 million, while South Korea – which only produces 5.23 percent of the world’s seaweed – generated $278 million in exports.

This is because Indonesia still relies on its comparative advantage (ie the low cost of production) instead of competitive advantage (ie the quality and price of the goods). Indonesia largely sells dried seaweed and intermediate goods like hydrocolloid, while South Korea processes seaweeds into high value products – including food, feed, fertilisers, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals.

Seaweed farms are now also being recognised for its environmental and ecosystem services while harvested seaweed is increasingly being converted into environmentally friendly products such as plastic substitutes and biofuels.

An expert opinion

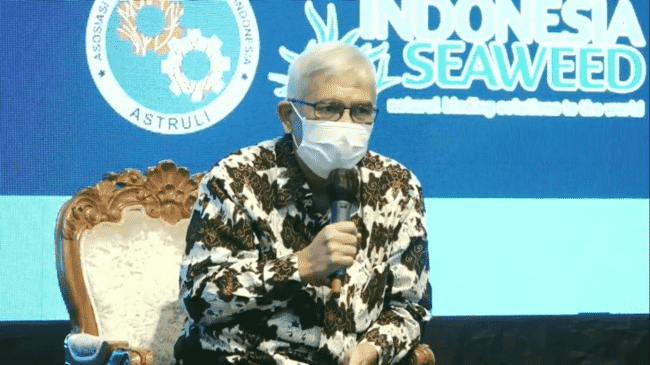

Pontas Tambunan, deputy chair of the Indonesian Seaweed Industry Association (Astruli), explained several challenges faced by the Indonesian seaweed sector at the Seaweed Fest 2021, which was held by the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (MMAF) at the end of last year.

First, he noted, Indonesian farmers don’t get a competitive price for raw seaweed. In recent times, the farmgate price of seaweed is only around 11,000 IDR/kg, but – because of the number of unnecessary links in the value chain – this has risen to 31,000 IDR/kg by the time the processors buy it. This makes production of seaweed derivative products more expensive and less competitive compared to other countries.

According to Tambunan, this condition can be resolved by the internet of things (IoT) and artificial intelligence (AI). These make it possible to detect a very high disparity between farm price and what the industry received, through the collection and processing of real time data.

IoT and AI also make it possible to find out real data on seaweed production in the field. Although the government predicted that seaweed production would reach 11.5 million tonnes in 2021, it seems that this amount wasn’t achieved. Tambunan said that producers are only reaching 40-60 percent of their production capacity, suggesting an information gap.

This is because of the limited resources of the industry, which puts them off investing in data processing, while there are also not enough digital startups in the seaweed sector. Therefore, Tambunan has asked the government to help provide real time, accurate data to give the industry certainty over the real price and volume of seaweed supply, which can improve production efficiency at the industrial level.

Second, according to Tambunan, too few seaweed companies are trying to produce higher value end products, while some of the derivative products are even less competitive, he argued, due to inefficient production processes. For example, the production of iota-carrageenan from Eucheuma spinosum requires alcohol. However, alcohol is quite expensive and he therefore wants the government to reduce the alcohol tax for the seaweed industry.

Meanwhile, Tambunan explained that higher value products which are ready to be consumed or used – such as seaweed noodles, dodol (Indonesian traditional food) or bio-plastics – are still being produced by small and medium scale enterprises (SMEs).

Thirdly, Tambunan argued, food safety and traceability are becoming key concerns for food products, including seaweed. This means that seaweed cultivation and processing techniques must meet high standards – for example by not using cultivation media which are made from plastic to avoid microplastic contamination.

The fourth challenge, according to Tambunan, is the need to increase the quality of the seaweed. This is affected by both the cultivation method and the quality of the seeds. To date, the seeds used by farmers are from wild stocks and independent producers, resulting in varied quality. However, the government has been developing seedlings through tissue culture in order to assist the needs of cultivators. This is in collaboration with SEAMEO Biotrop, a research and education organisation for tropical biology in South East Asia.

Meanwhile, to support increasing competitiveness, the government has also made seaweed one of its priority commodities, creating a supportive production ecosystem through the Kampung Budidaya (farming village) initiative and the provision of good quality seeds from their six technical laboratries.

Capitalising on seaweed sustainability

Unlike in the shrimp and finfish farming industries, the emergence of startups in Indonesia’s seaweed sector is still rare, particularly compared to Europe, the US and Australia. The seaweed startups in those countries use attractive marketing regarding the environmentally friendly nature of their products. This strategy can be imitated and modified by stakeholders in Indonesia, so that the enormous potential of seaweed can be optimised, says Tambunan.

Indonesia has more than 550 species of seaweed and a huge comparative advantage. If accelerated through competitive advantage, this will bring enormous economic benefits to many small farmers, the national economy and the environment.