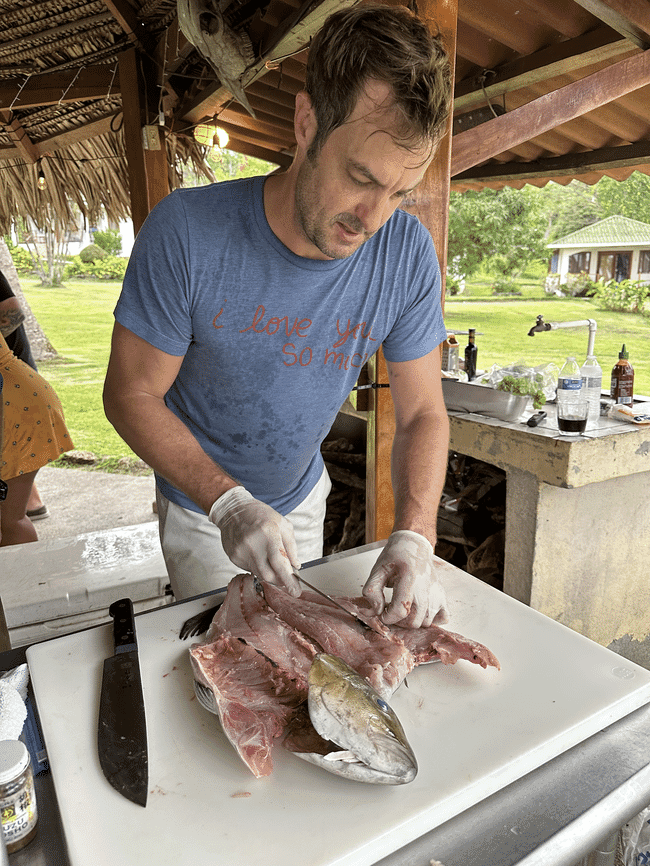

Farmers at Forever Oceans' kanpachi site, off the Pacific coast of Panama © Emily De Sousa

Organised by BioMar, the trip took De Sousa, Seaver and Phelps to some of the most spectacular fish farms in the world, including Open Blue’s cobia farm and Forever Oceans’ kanpachi farm – which are on the Caribbean and Pacific sides of Panama respectively – and Aquafoods’ snapper and rainforest tilapia farms in Costa Rican waters.

“It was an opportunity for us to see, first-hand, existing versions of some of the offshore aquaculture systems that we could one day see in the US – see the technology, assess the types of species that can be grown offshore and also taste the product,” De Sousa explains.

“Visiting the farms will help us engage with US consumers who may not know what offshore aquaculture is – or might have negative feelings about it,” she adds.

Despite having immersed herself in aquaculture for the last two years, in which she has emerged as one of the most vocal proponents of the sector, the trip left De Sousa with fresh insights.

“I’ve been to a lot of fish farms, but the level of technology in these offshore farms was on a different level – these farms are roughly 12 km offshore, there’s regularly 8 m waves, and it’s not always possible to get out there. So it was interesting to see the role that technology was playing to enable them to feed the fish and monitor the fish health from a distance,” she recalls.

© Emily De Sousa

She was also impressed by the farmers themselves.

“Going out in extreme conditions is definitely not for the faint of heart, and the people we met – roughing it out in those conditions – were very dedicated to their fish. Clearly these guys are doing something right and something they believe in,” she reflects.

De Sousa also witnessed a harvest when visiting Open Blue.

“Animal welfare is becoming increasingly important for consumers and it was really nice to see animal welfare was top of mind – both for the fish and for ensuring the quality of the fish,” she notes.

Meanwhile at Forever Oceans, where she was able to dive with the kanpachi, she was surprised by how sociable the fish were.

“They were swimming right up to us, bumping into us – they were very curious and it was fun to be in the pens with them,” she explains.

Outside the cages the sea was also teeming with life.

“People think of farms as dead zones, but they’re actually hubs of biodiversity. The day we were at Aaquafoods there were pods of dolphins passing us all day – swimming in between the cages; at Open Blue they see whale sharks all the time,” De Sousa adds.

De Sousa was surprised by how firendly the fish were © Emily De Sousa

Social licence

As a proponent of aquaculture on social media, De Sousa is only too aware of how the sector gets a decidedly mixed reception from the general public, but she feels that the lack of knowledge amongst the public is largely to blame and that, if more people visited farms, they would be less hostile towards the industry.

“In simple terms, it was quite evident to all of us on the trip that this is the future of food. There are various reasons why our current food systems are not working . Being out there and seeing the farms – how clean they are, how meticulously run they are, the care for the animals, and the quantities of high quality fish that they can produce – shows how aquaculture offers a lot of solutions,” she reflects.

“It checks all the boxes – it can be done at scale, it can be done in an economically feasible way and is very much the future,” she adds.

De Sousa was also intrigued by the chefs’ perspectives.

“It was interesting to hear that some chefs prefer farmed products on their menu because of the consistent quality of the product. While chefs still love wild product, it’s very much at the mercy of Mother Nature – no two wild fish will taste the same: two people sitting at the same restaurant, eating the same dish, can have two completely different culinary experiences,” she explains.

However, she also appreciates that gaining consumer acceptance for marine finfish species – such as cobia and kanpachi, which are both likely candidates for the US offshore aquaculture sector – will take time, as consumers aren’t as familiar with them as they are with species such as salmon.

“There’s going to be a lot of uphill battles in terms of consumer awareness and education around the species. The farms we visited in Central America are all selling into the US market, but have found that US consumers haven’t heard of them and don’t know how to cook them,” she notes.

Chefs are likely to play a key role in introducing less familiar species to US consumers © Emily De Sousa

Application in the US?

De Sousa says that the trip has given her some valuable insights. However, she’s also aware that not everyone is as well informed.

“I’d like to see more thoughtful conversations around aquaculture in the US, but my fear is that it’s become a very polarising political issue, which is unfortunate to see because it’s the future of how we’re going to produce food for the growing population of this planet,” she explains.

“But aquaculture in the US lacks the social licence it has in Panama and Costa Rica – we need to have more productive conversations with consumers, fishermen and other stakeholders. Consumer awareness should have started years ago. It didn’t, which is why aquaculture has such negative connotations. People don’t understand it and if consumer education doesn’t start now the narrative will be completely lost,” she adds.

And, as De Sousa notes, the consequences of failing to do so can be dire.

“I live in Canada and see that the west coast salmon industry is struggling – that’s what happens if you don’t secure social licence – and I think the benefits of a US offshore aquaculture industry are not being highlighted enough. Having those productive conversations now is vital for its future,” she concludes.