Indonesia has developed multiple strains of tilapia with improved growth and disease resistance

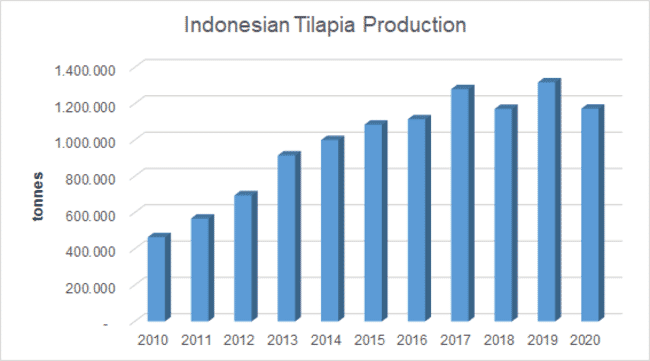

More than ten strains of tilapia have been developed by local researchers in the last two decades. The main objectives are to provide superior strains for farmers and help increase national production. And it seems this has been achieved, as there has been a near threefold increase in tilapia production in the last 10 years: from 400,000 tonnes in 2010 to 1.1 million tonnes in 2020. At the same time, tilapia is replacing carp as the country’s most widely cultivated species.

Despite not being native to the country, tilapia have proved suitable to cultivate in various water types and systems. The farmers use many methods: from traditional earthen pond systems, to intensive ones – including raceways, cages, biofloc systems, ponds equipped with paddle wheels, and even brackish water ponds.

For instance, in Lake Toba in North Sumatra, tilapia successfully replaced carp in the early 1990s after the latter suffered from a severe outbreak of koi herpes virus (KHV). Meanwhile, in other places, such as in Tasikmalaya-West Java, tilapia are produced in intensive monocultures rather than traditional polyculture operations.

There has been a near threefold increase in tilapia production in the last 10 years: from 400,000 tonnes in 2010 to 1.1 million tonnes in 2020

A short history of tilapia in Indonesia

After being initially introduced from Taiwan in 1969, Nile tilapia were quickly accepted by both farmers and consumers in Indonesia and became known as local tilapia, in order to distinguish them from the GIFT strain, which was imported from the Philippines in 1995 and 1997. Like the previous imported species, GIFT were also warmly welcomed by farmers. In 1989, Indonesia also imported the red tilapia – Chitralada – from Thailand.

In the 2000s onwards Indonesia started to develop its own strains of superior tilapia through its aquaculture research units. And in 2004 and 2006, the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (MMAF) officially launched genetically supermale Indonesian tilapia (Gesit), which had been developed by the Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology Indonesia (BPPT) in collaboration with IPB University and research unit in Sukabumi-West Java. Meanwhile Nirwana (nila ras Wanayasa) was developed by a research unit in Wanayasa-West Java. Both Nirwana and Gesit used GIFT as one of the sources of its development. By 2016, more than 10 other strains were developed by several research units.

Developing these new strains of tilapia has involved family selection, hybridisation and in one case, genetic engineering © Lilis Nurjanah

The development of these new strains of tilapia is carried out by family selection, hybridisation or – in one case – genetic engineering. Most of the development was focused on improved growth, disease resistance or adaptation to particular environmental conditions, such as brackish water.

Nirwana was the most actively developed and the third generation was launched in 2016. Each generation has at least a 30 percent better growth rate than the previous one. Together with Gesit, Nirwana has become the most popular strain in the field.

Meanwhile, Gesit is the only strain developed by genetic engineering to create supermale broodstock with YY chromosomes. If these breed with females from another strain they produce almost 100 percent genetically male tilapia (GMT). The GMT are claimed to grow 150 percent faster than females and can reach 600 g in six months.

Strains which can be farmed in brackish water were also developed – for example Srikandi, Jatimbulan and Salina – which can adapt to salinity levels ranging from 10 - 20 ppt. These strains were developed to fill shrimp ponds along the north coast of Java which had been mothballed after outbreaks of disease, in line with government plans to make these areas productive again.

The tilapia strains are largely distributed as broodstock to small-scale hatcheries

Tilapia strains that have been developed in Indonesia

No. | Name of strains | Year of release by MMAF |

1 | Nirwana (nila ras Wanayasa) I, II, and III | 2006, 2012, 2016 |

2 | Salina (saline Indonesian tilapia)* | 2014 |

3 | Sultana (seleksi unggul Selabintana) | 2012 |

4 | Srikandi (salinity resistant improvement tilapia from Sukamandi) | 2012 |

5 | Anjani (andalan jejaring nila Indonesia) | 2012 |

6 | Pandu (male) and Janti (female) | 2012 |

7 | Nilasa* | 2012 |

8 | BEST (Bogor enhanced strain tilapia) | 2009 |

9 | Larasati (nila merah strain Janti)* | 2009 |

10 | Jatimbulan (Jawa Timur Umbulan) | 2008 |

11 | Gesit (genetically supermale Indonesian tilapia) | 2004 |

*red tilapia

Opportunities and challenges

The developed strains are largely distributed as broodstock to small-scale hatcheries (unit pembenihan rakyat/UPR). This is a great economic opportunity which is not dominated by a few institutions or companies. Even the strains like black and red prima, from CP Prima, also use UPR channels to distribute their broodstock.

The hatchery manager of UPR Ernawati Galunggung, Lilis Nurjanah, who is also a user of Nirwana III broodstock, reveals that the new strains have changed the cultivation model in Tasikmalaya-West Java in the last decade from traditional polyculture to intensive monoculture. The faster growth of new strains makes cultivation more predictable and they are usually sold at 23,000 - 28,000 IDR/kg, due to the higher meat content, while local tilapia typically fetch only 14,000 IDR/kg. Nurjanah produces 1 - 1.2 million larvae per month to meet the demand from local farmers and the surrounding cities.

“This is a new opportunity, but also challenging. The challenge in the field was to choose the best practices to optimise broodstock performance. It took me two years to come up with the best formula. Even though there is a recommended procedure from the broodstock producer, modification is needed to adapt to environmental conditions,” she says.

The challenge also occurs at the grow-out level and, according to Nurjanah, a good strain of seed must be matched with good procedures, particularly relating to feeding and water management, which not all farmers realise. As a result Nurjanah also gives consultations to her customers, noting that those farmers who are more open-minded and try what she suggests have better harvests and a more sustainable production model.

.jpeg?width=650&height=0)

The new strains' faster growth makes cultivation more predictable and the finished fish have a higher meat content

Meanwhile Daru Handoko, a grow-out farmer from Tasikmalaya who favours the Nirwana III strain, says it allows him to produce fish intensively with more cycles in a year. His ponds are 1.2 m deep with a stocking density of 80 fish per m3. He also uses a range of technologies, including paddle wheels, to maintain good dissolved oxygen levels and improve carrying capacity, as well as automatic feeders to optimise feed management.

"With such a system, I stock seed at 2-3 cm (12 g) and harvest in approximately two months when the fish are at least 125 g, as the local market demands. The success of cultivating new tilapia strains is not only determined by quality seed, but also by good feeding and water quality management,” he notes.

For a modern farmer like Handoko, the challenge not only comes from the cultivation itself, but also from the market. He says that while he uses new technologies, he still depends on the traditional market in the end. This is quite challenging because the use of new technology requires additional costs. To deal with this, Handoko is innovating by selling frozen fish.

-

Despite tilapia being a non-native species, farmers in Indonesia have produced the fish in a variety of systems and water types -

-

Conclusion

The many strains of tilapia that have been developed in Indonesia have brought opportunities as well as challenges for farmers. Forward-thinking farmers can select tilapia which are suitable for their environmental conditions and find the best practices for their cultivation, and in the end boost their productivity. However, assistance from the government or the private sector is needed for those farmers who do not understand the options well enough. It is also important to underline that successful farming is not only determined by the quality of the stock strain, but also other factors, particularly water and feed management.

The development of current strains is still focused largely on growth and not yet on resistance to specific diseases. There is no specific pathogen-free (SPF) broodstock or fry, neither are there any strains that are resistant to pathogens such as Streptococcus or tilapia lake virus (TilV). Selecting tilapia for such traits could be the goal of research in the coming years.