So notes Gorjan Nikolik, seafood analyst at Rabobank, in a new update on how the shrimp sector of various regions has performed since the outbreak in January.

Despite poor prices during 2019, the shrimp sector started the year with a great deal of optimism, Nikolik reflects.

“Prediction by shrimp experts at conferences such as GOAL, in November, and NFI, in January were bullish, but by Chinese New Year demand had started to crash and importers in the US and EU were stockpiling shrimp. By April/May they couldn’t shift it,” he explains.

“In May shrimp imports to the US crashed by 30 percent – the lowest figure for seven years. India’s exports to the US fell by 57 percent in May and 43 percent in June,” he points out.

© CP Foods / NFI webinar

Ecuador

Meanwhile other countries started to suffer too, not least Ecuador.

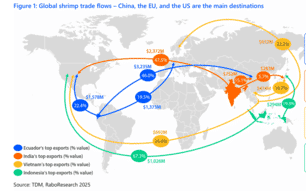

“Ecuador has seen double digit growth for the last 7 years and has been very profitable using a business model that focuses on selling unprocessed shrimp, (head on – shell on), mainly to China, which have been produced as efficiently as possible. It’s been a fantastic story, until about now – their shrimp was mainly for the food service sector and they don’t have the processing capacity to produce shrimp for the retail sector. Nor do they possess activities downstream in the value chain such as import or distribution in the destination markets to shift large volumes of their exports to the EU or the US in time,” Nikolik explains.

And it was one, now infamous, incident that acted as a catalyst for Ecuador’s troubles.

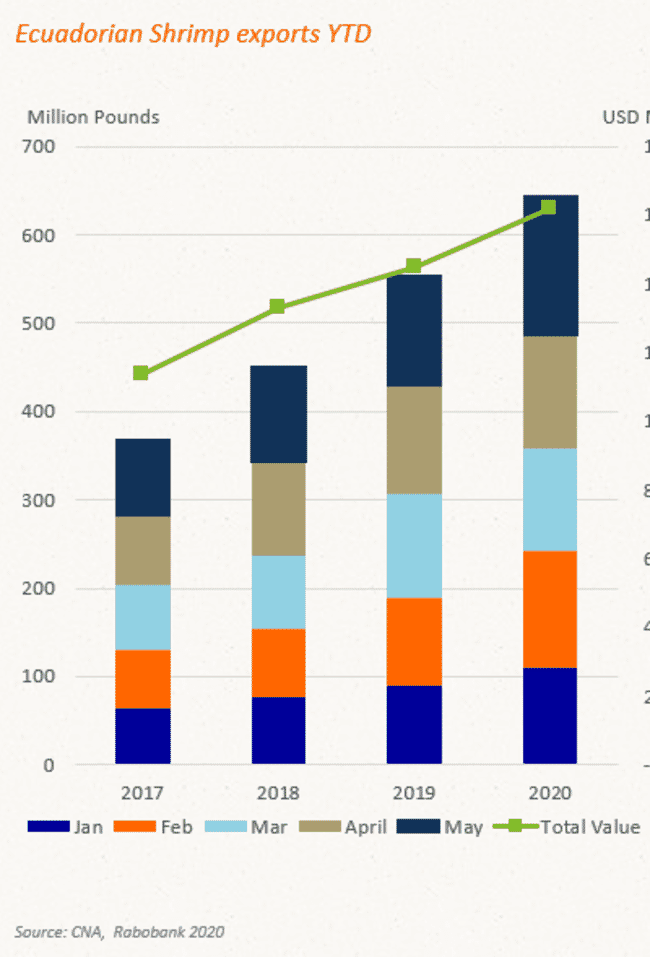

“Ecuador’s shrimp sector had been performing well, with exports up by 82 percent in the first five months of the year. But, in June, the detection of traces of Covid-19 on a packet of Ecuadorian shrimp by Chinese officials led to a ban on imports from four of Ecuador’s largest shrimp exporters and then a general decline across the board,” he reflects.

The discovery caused Ecuador’s exports to China to drop from 120,000 tonnes in May to 60,000 tonnes in June, to around 10,000 tonnes in July. Meanwhile exports to the rest of the world increased, but couldn’t make up for the shortfall – rising from 40,000 tonnes, to 60,000 tonnes to 70,000 tonnes.

“It’s kind of weird – it was detected on one packet out of 245,000; it was a just RNA of the virus, not active live virus ; and it was on the outside of the packaging – so the reaction from the Chinese authorities is way out of proportion. Everyone has a theory – some people think the Chinese were using it as leverage for trade negotiations over other issues; some people think it was related to Ecuador exporting the shrimp via Vietnam; some people think China was trying to protect its own shrimp sector, as 60 percent of the Chinese shrimp market had been served by Ecuador,” he explains.

“Whatever the reason it certainly provoked a great deal of fear, a decline in consumption, an oversupply of shrimp and a crash in prices for Ecuador’s farmers of a phenomenal 25-35 percent compared to the same period last year. It’s tough to be an Ecuadorian shrimp farmer and almost all will be selling below production cost. At some point Ecuador will have to diversify its market an develop its own processing sector – they need to rely less on China and have a more balanced approach,” he adds.

Nikolik also speculates that while Ecuador’s long held-belief in the value of extensive production holds true, and is the core of their past success, it is a model that is unique to Ecuador and is unlikely to work in the other established shrimp farming countries. Elsewhere, intensification is the right move.

“Intensification doesn’t just mean greater stocking densities, it also means better FCRs, more control over biosecurity and lower mortalities. It’s really reducing disease pressure and mortality levels that set good companies apart,” he explains.

“But, in Ecuador, the key is being more vertically integrated into the markets to supply less commodity and to be able to sell directly to retail as much as possible,” adds Nikolik.

© Rabobank

Vietnam

Vietnam, on the other hand, benefitted from having established sales channels to many different countries, he points out.

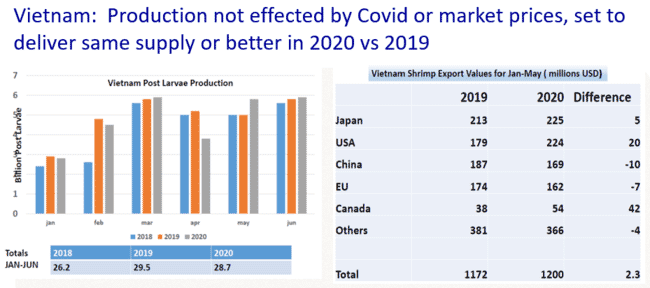

“Unlike Ecuador, which is so reliant on one country, Vietnam has been able to pivot towards US and Canada, away from China and EU,” he notes.

Although growth has not matched pre-pandemic expectations, the story has still been a positive one.

“The Vietnamese sector had a very bullish outlook prior to the pandemic and they were only mildly affected by the initial Covid outbreak in China – exports until the end of May were actually 2.3 percent higher than the same period last year and the most recent data shows that June was a great month for Vietnamese exports too,” he adds.

As well as the wide range of markets catered for by the Vietnamese, the country has also benefitted from an unusually low incidence of Covid-19.

“It has emerged as one of the countries least effected region by Covid in the world – there’s a theory that the Vietnamese may have a degree of immunity as the bats linked to the original outbreak are quite common there,” says Nikolik.

“On the other hand, they have experienced challenging climatic conditions and, as a result, local sources say farmers are likely to deliver around 530,000 tonnes, which is the same volume as last year,” he adds.

Conclusions

Summing up, Nikolik reflects that the Covid-19 pandemic is likely to lead to the increased use of technology – combined with increased professionalisation and consolidation – in the global shrimp aquaculture sector.

“The bottom line is that major losses are expected at farm level across the board, but these won’t be equal in all regions – those countries that are dependent on the food service sector will be hit the hardest, and it will also be dependent on where you sell your shrimp. Regardless of this, it will take time for demand to fully recover, and there could regions where the smaller farmers will exit shrimp farming, leading to consolidation,” he reflects.