© Georgie Bull

Seahorses are largely to blame, explains Parry, when asked how he’s ended up running a series of projects relating to seagrass. It’s thanks to the public’s appreciation of the hippocampus genus that aquatic plants have now been the focus of his work for over seven years.

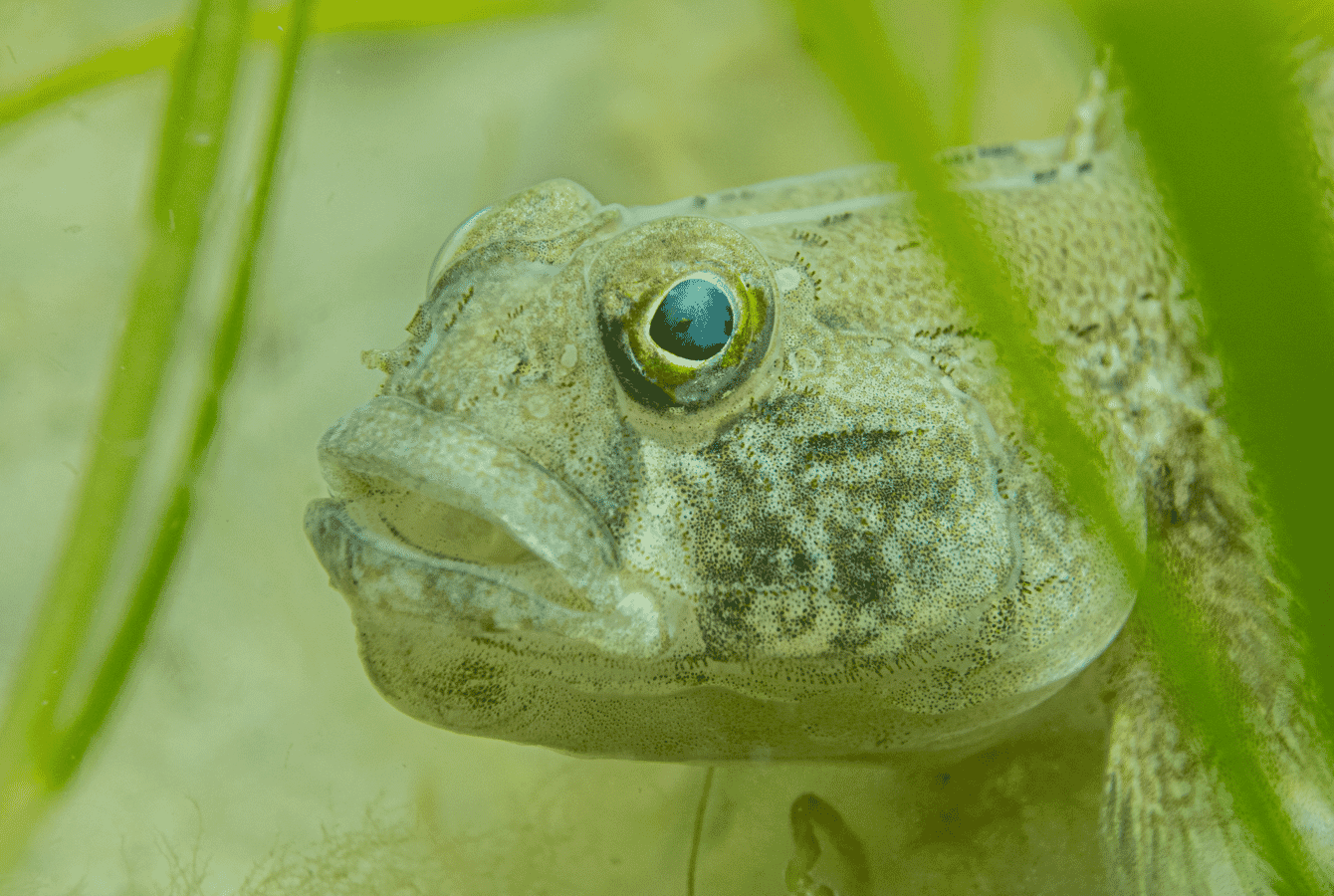

“The Ocean Conservation Trust (OCT) was originally interested in a project counting the number of seahorses in the seagrass beds. They’re poor swimmers and need a canopy to hold onto and to hide in and seagrass is ideal as it grows in calm, sheltered, shallow bays,” he reflects.

“But rather than focusing on the umbrella species [ie the seahorses] to get buy-in, the OCT decided to instead look at the relationship between the health of a seagrass bed and the fluctuations of animals on the seagrass. Let’s focus on the health of the seagrass bed and the fauna, rather than specifically for the seahorses,” Parry explains.

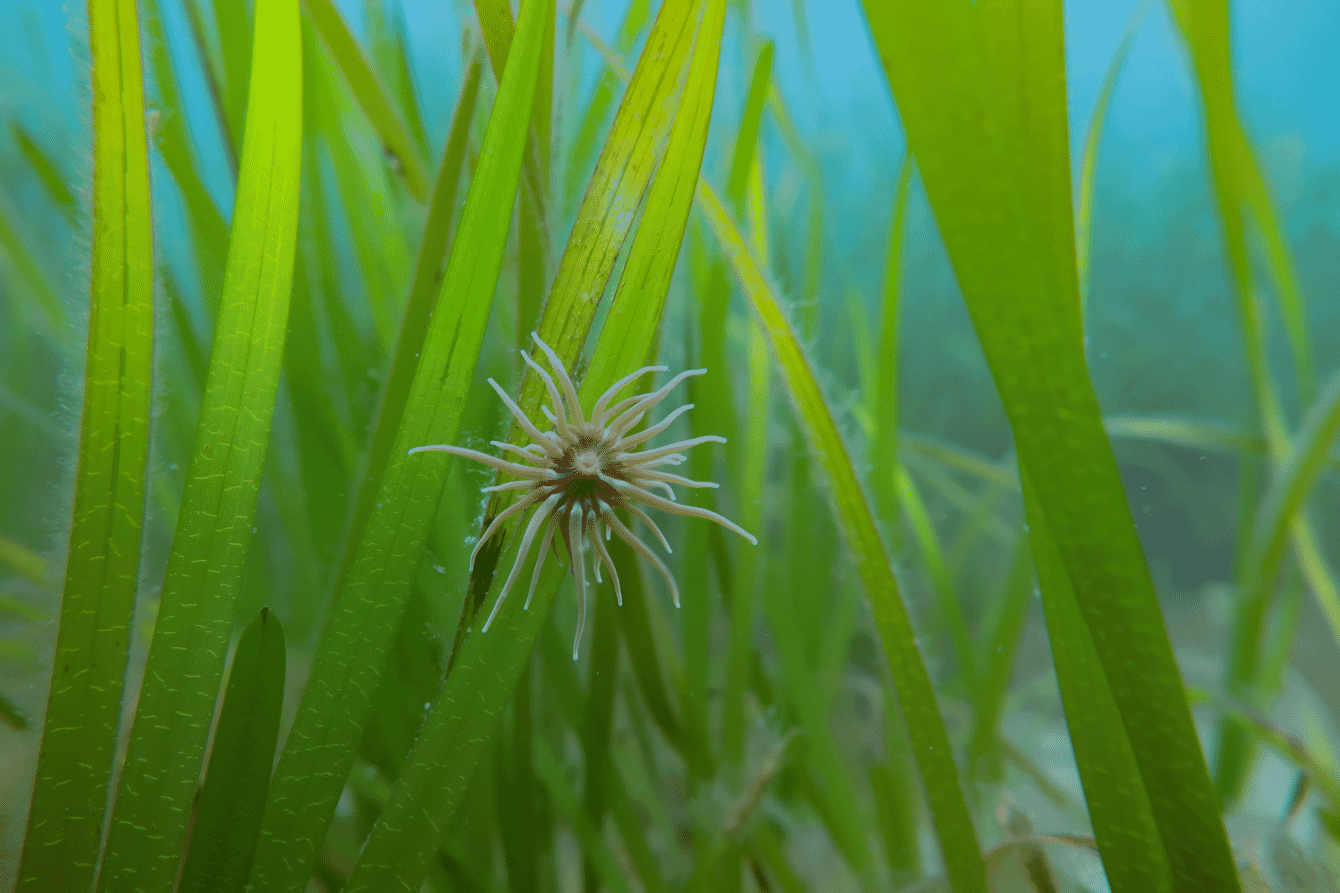

The OCT's decision turned out to be both sensible, and widely supported, and as development officer, Parry ended up running a three-year project, which involved over 150 volunteer divers, who helped to record all the animals that seagrass was supporting – not only seahorses, but also a wide selection of other organisms, including finned fish, shell fish, crustacean, sea squirts and bryozoans.

The study helped to highlight the vital habitat provided by the seagrass. And, in doing so, also helped to illustrate why the loss of up to 90 percent of the UK’s seagrass cover in the last 90 years was potentially so devastating for the country’s biodiversity.

To make matters worse, as the OCT realised, the loss of such vast swathes of seagrass also equated to a loss of a wide range of vital ecosystem services – including sediment stabilisation and the storage of both nitrogen and carbon dioxide. Despite these benefits seagrass is, he admits, not always an easy sell.

“In many ways it’s the ugly duckling of marine conservation – most international conservation organisations go for headline species – like rhinos or whales or tigers. We’re moving away from headline species to the habitat that these things occupy,” Parry reflects.

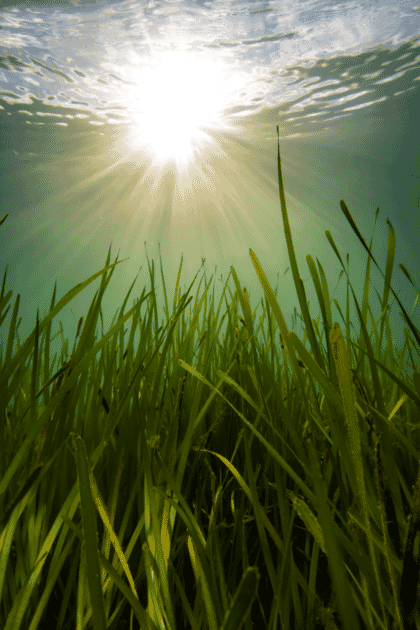

“It a fairly homogenous environment – a group of plants on a flat seabed, under shallow water, in a meadow that can be up to 2km long. It’s not as panoramic as a coral reef, and there are fewer ornate fish, but it’s also one of the most productive habitats we have, and arguably more significant in terms of biodiversity. They are also on our doorstep, people can access them, so they’re more tangible,” he adds.

Despite the ugly duckling label, the Ocean Conservation Trust has raised considerable funding for the seagrass projects. After the original habitat survey, Natural England encouraged the trust to join in an application for EU LIFE funding, and to restore seagrass meadows designated in Special Areas of Conservation under the Natura 2000 initiative.

They also took part in a joint bid alongside the Marine Conservation Society, Natural England, Plymouth Council and the RYA, landing £2.4 million for a follow-up project. Since then Parry has since been approached by a number of companies, including a “ corporate companies” to look into investing in seagrass restoration as a means to mitigate their carbon footprint.

“We were originally always talking about seahorses to raise interest in seagrass, now 90 percent of the comments relate to carbon capture. Sadly blue carbon [ie carbon stored in our oceans] is not yet recognised as a means to offset carbon emissions and after the outbreak of Covid, sponsors had to withdraw support,” he says.

In 2020 Parry did, however, manage to land £250,000 from the UK government’s Green Challenge Recovery Fund.

“The government is making encouraging moves towards green recovery and creating an economy based on this, including habitat restoration, and biosequestration of carbon – as can be achieved by seagrass – is now a big deal,” Parry reflects.

According to the Ocean Conservation Trust, seagrass is particularly well suited for the role – much more so than terrestrial plants.

“When a tree, for example, dies the carbon is released back into the atmosphere. A seagrass meadow can store carbon 35 times quicker than a forest – filtering it from the water and burying it in the sand – and the absence of fire and air underwater means that it’s very unlikely to be released again,” he explains.

“Tens of thousands of hectares of seagrass meadows could be restored in the UK alone and it’s an idea that also hugely supported by the fishing industry, as it’s the second or third most valuable habitat for ecosystem services on the planet even without considering the carbon. And must be one of the most valuable habitats when considering all the services provided by the habitat,” he argues.

Such is the basis for Parry’s plans to start to restore the UK’s seagrass meadows. However, he admits, that there are a few technical challenges to overcome.

“There are two types of seagrass beds – subtidal and intertidal. The subtidal ones can be as much as 5m under the surface making it hard to secure the seedlings.

Collecting the seed is also not straightforward, says Parry, as the beds only produce seed when stressed, otherwise relying on vegetative growth. And he notes that there’s a low germination rate of the seed that is collected.

“We need to keep the seed free from infection and we still need to find the trigger for germination. Is it temperature, or photoperiod?” he wonders.

According to the Ocean Conservation Trust there are only 7,600 hectares of seagrass currently remaining in UK waters, a figure that’s dropped by 40 percent in the last 50 years. However, Parry says that there are around 76,000 to 80,000 hectares that are suitable for restoring the plant, as efforts to conserve the remaining beds under threat.

“We’ve not yet seen a reverse in the decline of seagrass, despite conservation efforts – restoration is essentially the last-ditch attempt,” he reflects.

The good news is that attempts to restore the plant in other countries appear to be working and Parry points to the successful restoration of 200 hectares in Chesapeake Bay, the effect of which has already been hugely beneficial for the scallop sector, as the new meadows are an ideal nursery for scallop spat.

© Georgie Bull

Looking ahead, the Ocean Conservation Trust's plan is – initially – rather more modest, but in the longer-term he sees scope for large-scale restoration of the plants.

“Within three years, we’d like to be in a place to actually restore tens of hectares of seagrass. Within five years, we’d like to have developed a mechanised planting process, and have restored hundreds of hectares. Within 10 years we’d like it to be possible for private companies to invest in seagrass restoration as a means of tackling climate change and for the restored areas to be recognised and protected,” says Parry.

“It’s also important that blue carbon is recognised in bringing much more to the table than just carbon. Many carbon [terrestrial] trading schemes are not sequestering carbon, just fencing off forests, essentially making them conservation projects. Seagrass, on the other hand offers a net gain – sequestering carbon and creating a new habitat on barren sand, without competing for land that could be used for other purposes,” he adds.

It’s early days and, unlike the Chesapeake project, the Ocean Conservation Trust doesn’t have $56 million at his disposal. However, once the OCT has managed to develop the capacity – both biological and technological – to restore meaningful quantities of seagrass, what was once perceived as the ugly duckling might be more widely appreciated as an emerging swan in our battle against climate change.