Food researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, are introducing a new sorting technology that means we get five good cuts from fish and not just the fillet © Pixabay, Haizhou Wu and Ingrid Undeland, Chalmers University of Technology

In the meat industry, it’s common practice to turn the whole animal into food products. In the fish industry, over half of the weight of the fish ends up as side-streams which never reach our plates. This takes a toll on the environment and is out of step with Swedish food and fisheries strategies. Now, food researchers at Chalmers are introducing a new sorting technology that means we get five good cuts from fish and not just the fillet. A herring processing plant on Sweden’s West coast is already implementing the new method.

When the fillet itself is removed from a fish, valuable side-streams remain, which can be turned into products such as nuggets, mince, protein isolates or omega-3-rich oils. Despite such great potential, these products leave the food chain to become animal feed – or in the worst case, get discarded. To exploit valuable nutrients and switch to more sustainable procedures, the way we process fish needs to change.

All cuts are treated with care

“With our new sorting method, the whole fish is treated with the same care as the fillet. The focus is on preserving quality throughout the entire value chain. Instead of putting the various side-streams into a single bin to become by-products, they are handled separately, just like in the meat industry,” says research leader Ingrid Undeland, Professor of Food Science at the Department of Biology and Biological Engineering at Chalmers.

Ingrid Undeland, Professor of Food Science, Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden © Anna-Lena Lundqvist, Chalmers University of Technology

The research was conducted as part of an international project called Waseabi. Waseabi is a four-year, interdisciplinary project aimed at making better use of side-stream products in the seafood industry by stabilising them and developing new methods of producing food. Researchers from Chalmers University, a key partner in the project, recently published their results in the scientific journal, Food Chemistry.

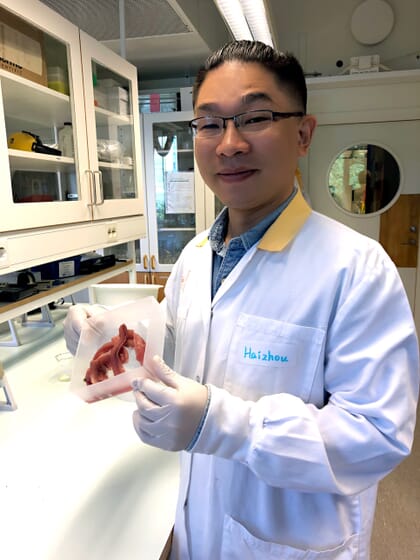

“Our study shows that this type of sorting technology is important, particularly as it means we can avoid highly perishable side-stream cuts being mixed in with the more stable cuts. This new method brings fresh opportunities to produce high-quality food,” says Chalmers researcher Haizhou Wu, first author of the scientific article.

The new sorting technology means that fillet, backbones, tailfin, head, belly flap and viscera can all be separated. The backbone and head are most muscle-rich and thus well suited to becoming fish mince or protein ingredients. As the belly flap and intestines are rich in marine Omega-3, they can be used for oil production.

Haizhou Wu, food researcher, Department of Biology and Biological Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden © Mia Halleröd Palmgren, Chalmers University of Technology

The tail fin has a lot of skin, bones and connective tissue and is therefore well suited to such things as producing marine collagen, a much sought-after ingredient on the market right now. In addition to food, marine collagen is also used in cosmetics and nutraceuticals, with documented good effects on the health of our joints and skin.

“The interest is there”

The new sorting method for separating the five different cuts is being introduced at one of the partner companies in the research project. Fish processing company, Sweden Pelagic in Ellös on the island of Orust is already using parts of the method in its production and has had good results.

“The sorting technology gives us many more opportunities to develop healthy, new and tasty foods and to expand our product range. This year, we estimate we’ll produce around 200 to 300 tonnes of mince from one of the new cuts and we aim to increase that figure year on year. The interest is there, in the food industry and public meal production segments like school catering,” says Martin Kuhlin, CEO of Sweden Pelagic.

Sweden generates an estimated 30,000-60,000 tonnes of seafood side-streams each year; 35-70 times more than the Swedish cod catch © Haizhou Wu, Chalmers University of Technology

The hidden opportunities in fish processing

The EU’s fish processing industry is significant and generates an annual turnover of nearly €28 billion whilst employing over 122,000 people. However, the industry faces several challenges. For instance, an estimated 1.5 million tonnes of seafood side-streams are produced in Europe, based on a production of 5.1 million tonnes of fish caught.

In Sweden, it has been estimated that 30,000-60,000 tonnes of seafood side-streams are generated yearly; some 35-70 times more than the Swedish cod catch. This means that the current utilisation of aquatic biomass for food is far too low. When producing fillets, up to 70 percent of the aquatic resources end up as side-streams, which are either used for low-value products such as animal feed or discarded, which takes a toll on the environment and sometimes also the companies involved.

Read about a previous research advance from the project: New dipping solution turns the whole fish into valuable food.