A visit to the Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research (CCAR) is not unlike a visit to a marine menagerie. Lumpfish grow in one tank, polychaete worms in another.

In one building tanks with curtains around them keep halibut in the dark to mimic their deep underwater habitat. In another I see yellowtail swimming in large cylinders. The small handful of feed pellets that I throw in is devoured almost instantaneously. The tour extends on to coolers with seaweed seeds, urchins, labs and greenhouses.

CCAR is a business incubator located in Franklin, in the far east of Maine. Stephen Eddy and Melissa Malmstedt host me for the day to show me many of the wonderful projects that are going on. The goal is simple. This part of the University of Maine is focused on advancing the knowledge and capabilities of aquaculture for the benefit of the people of Maine, and the industry as a whole.

The CCAR was founded in 1999 by the University of Maine on the former site of Penobscot Salmon. At the time, this was a state-of-the-art recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) for growing juveniles to the smolt phase before moving to offshore pens. When the company ceased operations the University of Maine bought the site at auction and has since employed experts at raising many species including tilapia, salmon, flounder, California yellowtail, Atlantic halibut, eels, marine polychaetes and sea urchins. They exist as a business incubator to investigate new ideas in commercial and restorative aquaculture.

The eel deal

American Unagi is a relatively new company, which grows eels in RAS, and has taken the industry by storm, with accolades including the sought-after Fish 2.0 ICX prize for innovation.

Normally, any eel that you consume may have circumnavigated the globe before getting to your plate. Many of these animals are harvested as young glass eels off the coast of Maine. They are then sold live to dealers who ship them off to Asia, where they are farmed for another 12-16 months to market size. The fishery is managed by both the Maine Department of Marine Resources (DMR) and the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC), and founder Sara Rademaker decided to develop a local option. All her eels are locally sourced and raised off the coast of Maine.

Rademaker had been working in aquaculture for nearly 15 years when she took the opportunity in 2011 to come back to Maine and begin developing her own business. Since 2014, American Unagi has been growing locally harvested glass eels to market size using RAS systems and has been increasing its production every year. They are especially excited about plans to break ground on a new facility in Waldoboro in the coming months and building the first eel facility of this size in the country.

Rademaker explains that they “utilised CCAR’s business incubator as an intermediate space for scaling our production and expanding markets; while building we constructed our own facility in the mid-coast area. The ability to walk in as a company and utilise several virtually turn-key RASs is truly a unique resource within the US.”

The benefits of the infrastructure and staff also extend to learning and training, in an industry where expertise and experience are at a premium. “[The] CCAR has been a great space for allowing our staff (some new to RAS) to become familiar with small versions of the systems we will be using in our own facility,” reflects Rademaker. “It would have been a significantly longer process without the use of the CCAR incubator spaces.”

Organic algae

Sarah Redmond was once based at CCAR as a Maine Sea Grant extension specialist in seaweed, and is the founder of Springtide Seaweed. Springtide is the largest organic seaweed farm in North America and operates in eastern Maine. Located a stone’s throw from the CCAR and just east of the resort town of Bar Harbor in tiny Gouldsboro, they operate a state-of-the-art USDA Organic seaweed nursery. Redmond has been part of the seaweed industry in Maine since 2010 and is a leader in the field. She explains what incubator programmes like those at the CCAR have meant to her and her company.

“While the state of Maine has great aquaculture potential, we lack the necessary infrastructure to develop these systems and methods. CCAR provides this infrastructure, in a way that is accessible and supportive of new business development. It’s a unique facility that provides essential aquaculture infrastructure for the development of new ventures in the state. It provides the water, power, equipment and knowledge infrastructure necessary for cultivation of almost any kind of aquatic organism. Every aquaculture operation is built upon clean water, 24/7 reliable operations and access to the proper equipment and space,” Redmond explains.

Springtide leases space at CCAR for production of seed, as well as a large greenhouse that they use for drying the product once it’s been harvested. “These spaces are essential for the operation of our business.” Redmond reflects. “We can rely on clean, high-quality seawater as well as a controlled environment and a failsafe system for success with 24/7 site management. These are not available anywhere else in the state.”

The centre’s staff also provide a vital resource. As Redmond notes: “CCAR has always been helpful to our business by providing support in day-to-day operations, during emergencies and partnering in research and development.”

Turning the worms

Not every project that comes to the CCAR is successful. Stephen Eddy is still hopeful that a Maine company will take up the opportunity of growing the halibut and sea worms that they continue to work with. He notes that, although halibut is farmed commercially in Canada, here in Maine “there is great market value for the halibut, and very limited fisheries. Right now, there is a hatchery bottleneck but much of the technique and expertise and technology is well understood.” The CCAR has been working with halibut almost since its inception, and the species has been a focus in Denmark and Norway for over 20 years.

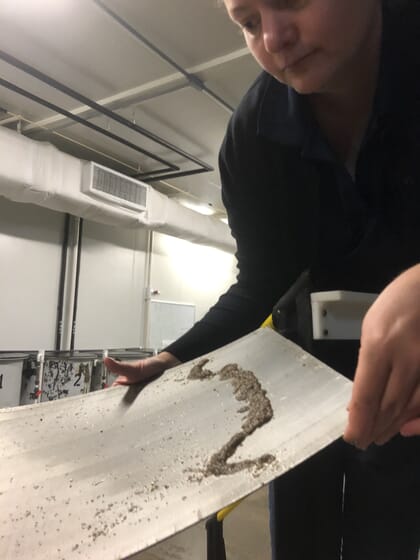

© Tim Harder

The Alitta virens worms (known as sandworms in the US or ragworms in the UK) grow in small, sand-lined tanks. They have a growth cycle of less than six months and can survive a very wide range of environmental conditions and stressors. Some time ago, the now-defunct UK company Seabait Ltd was provided with technology for systems to grow the animals. In 2003 the CCAR constructed a system capable of growing 2.5 million worms to harvest size per year (this is equivalent to approximately 7 tonnes). They were supplied to anglers as bait and to fish farmers as highly nutritious feed components. They can even be considered for environmental remediation for organic waste near fish farms as part of a larger integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) method. In 2008 Seabait went into receivership and Seabait Maine LLC was dissolved. The CCAR continues to carry out research into marine polychaete aquaculture, anticipating that this species will be one of the next candidates for Maine aquaculture.

Kingfish Zeeland

The work of the centre is also attracting international attention. Acadia Harvest was once a promising young business which was growing yellowtail for food consumption. After the company failed to attract enough capital to commercialise, the CCAR retained ownership of the broodstock, held in a state-of-the-art RAS on site. These animals can grow from egg to saleable size in about one year, and the broodstock are prolific. Melissa shows me one of the filters designed to capture eggs and explains that the fish can produce up to 500,000 eggs in a single evening.

This broodstock led to an important opportunity for the CCAR and the state of Maine with the announcement by Kingfish Zeeland that it planned to establish a new, $110 million kingfish RAS farm in Jonesport. The existence of a local and well-established broodstock of their target species is a distinct advantage for a company moving to this area and will create a strategic partnership for both the University of Maine and the Dutch company.

The important work of the CCAR provides a critical link between the technical expertise required for this type of work and the adventurous entrepreneurial spirit required to start new businesses. Its value is accentuated by virtue of its location – near vast natural resources for aquaculture but among one of the smallest populations in the country. The team in Franklin remain on the cutting edge, and perfectly placed to grow their most valuable crop: new business in Maine.