After catching juvenile Pacific bonito (Sarda chiliensis chiliensis) specimens in the wild, researchers were able to condition 11 of them in a recirculating aquaculture system (RAS), have them spawn and produce viable eggs – a first for the species.

The case study, outlined in Aquaculture reports, uncovered key information on the embryonic and juvenile development of Pacific bonito, along with their behavioural patterns and ideal production conditions. The researchers stress that their work establishes a baseline for production and forms a crucial first step towards capture-based aquaculture of the species. It could also, in time, lead to fully closed-cycle, land-based production of Pacific bonito.

How to culture a new species

Farming marine finfish species offers one possible solution to overfishing. Aquaculture advocates stress that commercially producing high-value fish can prevent natural stocks from being exploited and stem population declines.

However, researchers and fish farmers need extensive, species-specific information before they can begin production. In addition to feed and water quality parameters, producers need a reproductive strategy – data on how particular fish spawn, develop and behave in groups – before they can successfully adapt wild fish to aquaculture production.

Any information on embryonic morphology of the target species or ideal environmental conditions would give farmers huge advantages. Farmers could identify viable eggs in the wild or in production facilities and rear healthier larvae and fingerlings. They could also adapt the farming environment to meet the fishes’ needs, ensuring successful spawning and better production indexes.

© IEO

The study and key results

The researchers captured 24 Pacific bonito that weighed less than 1kg off the coast of Chile. The fish were then transferred to a 75m³ RAS for conditioning. They were weaned from their fresh fish-based diet to a commercial aquafeed over a four-week period.

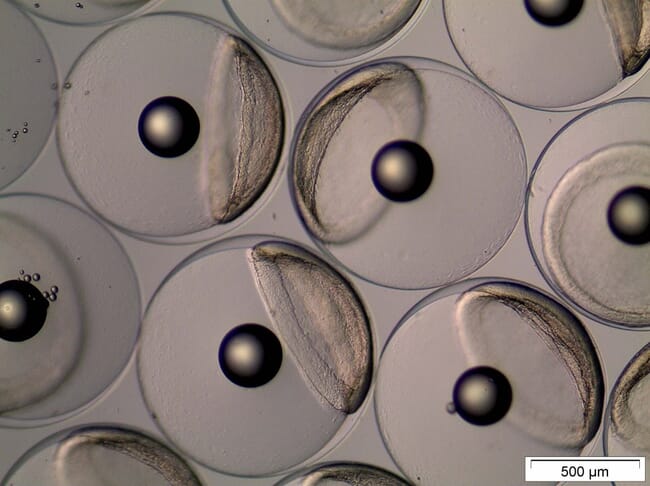

After 14 months in the RAS, the fish spawned spontaneously. The researchers removed the eggs from the tanks and tracked their development through embryonic phases and hatching – publishing the first development dataset for Pacific bonito. The spawning produced viable juvenile fish, suggesting that wild-caught broodstock could be used as a starting point for commercial aquaculture production.

Welfare considerations

The researchers raised some welfare concerns when they discussed transporting the fish from the ocean to the lab. After their initial transfer, the fish started swimming quickly, hitting the walls of the tank and each other. Multiple fatalities were recorded before the fish reached the lab. To reduce the risk of burst swimming during transport, they note that fish should be stocked at three individuals per m³ of water. They also suggest transporting the fish at a lower water temperature to decrease their stress levels.

Feeding the fish was an additional challenge. Since the bonito were accustomed to their natural diet (forage fish and squid), many initially refused the commercial aquafeed used in the trial. The researchers recommended feeding lab specimens raw fish and live foods and gradually switching over to a commercial feed. The switch should be done as quickly as possible though, they note, as a successful feeding regimen will allow wild-caught specimens to bounce back from transport stress and thrive in their new environment.

The next step

Although this study outlines the development life cycle of larvae and establishes a production baseline, researchers need additional information before commercial production of Pacific bonito can become a reality. Catching and transportation protocols need to be established (and drastically improved) to minimise fish stress and increase the survival rate of wild-caught broodstock.

Future studies should focus on larval feeding and egg rearing protocols, to ensure the yolk-sac remains intact. This will give Pacific bonito aquaculture a successful start and allow it to quickly transition to an on-shore hatchery-based business model, they conclude.