Between 2010 and 2016, tuna farming in the Mediterranean looked like the next big thing. Until four or five years ago all the EU countries bordering the Mediterranean, as well as Turkey and Israel, had ongoing projects – from both the public and private sectors – striving to create this new fish-farming sector, as extensively discussed in the 2017 report The closed cycle aquaculture of Atlantic bluefin tuna in Europe. Currently, however, it seems that only Spain is active and moving forward, whereas there are no signs of activity in France, Greece, Italy or Turkey.

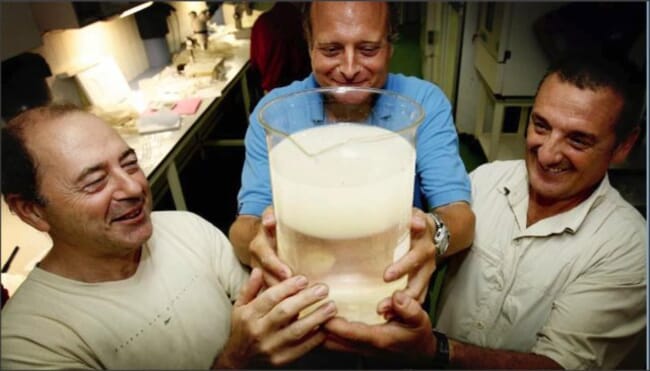

© IEO

In the past, much of the sector’s motivation was inspired by the advances that the EU-funded tuna projects SELFDOTT and TRANSDOTT were making. Japan was also reporting commercial successes – with farmed-from-hatchery juveniles being marketed and accepted by a very discerning public. During those years, wild tuna stocks became heavily overfished and, as a result, strict fishing quotas were introduced. As the amount of wild-caught tuna available to be ranched was reduced, operators began looking for an alternative source of these valuable fish.

By the time the TRANSDOTT project ended in September 2014, most major hurdles that were preventing the industry from taking it to the next level had been cleared. Important hatchery obstacles to do with broodstock husbandry, egg production, egg incubation, larval rearing and weaning of juveniles on to dry diets had all been successfully negotiated, with results and information having been made widely available to the private sector. It’s true that there were still some unresolved issues that needed further work – one being a viable method for transferring fish from the hatchery to the cages; another was developing a sustainable grow-out diet that would be accepted by the tuna. However, these were not major obstacles and, within a couple of years, both issues were resolved by the private sector.

In 2016-2017, Skretting as well as Marubeni Nisshin, developed a soft diet that is acceptable to tuna. For transfer to cages, Royalthon (a Greek hatchery company, which was managed by Gidon Minkoff, one of the authors of this article) presented a novel approach in 2015 which was validated and achieved a success rate of over 80 percent.Yet, despite these advances, little progress seems to have been made in bluefin tuna farming in the region since. After some years of silence, where is the sector standing now?

Update: Greece

Greece’s aquaculture sector has just come out of a long phase of reorganisation. Between 2014 and 2016, a number of leading companies in the sector went bankrupt and were taken over by the bank. Since then the farms have been restructured and in 2019, with the government’s involvement, their assets were sold to private-sector groups. There is no doubt that this situation significantly dampened any appetite for new fish farming businesses in Greece, and in tuna farming in particular.

Tuna spawning and egg availability is no longer a problem. However, according to Dr Constantinos Mylonas, research director at the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research in Crete, there is a problem with the uptake of the technology by the Greek hatchery sector, which is more focused on reviving its large bream and bass operations. These hatcheries work on an annual cycle, initiating production in September and sending out the last fish to the farms in July. In August, the hatcheries are shut down for biosecurity purposes, as well as for maintenance, and the staff take their annual leave. Since tuna spawn in late June through July, their production conflicts with the operating procedures of the hatcheries. Not shutting down in August would risk the entire production of the following year.

© IEO

Another impediment is the piscivorous feeding requirement of tuna larvae. From their third week, tuna larvae move on to feeding on the newly hatched yolk-sac larvae (YSL) of other species. Unfortunately, in late July the broodstock in bream and bass hatcheries are no longer spawning, making it difficult to have sufficient live feed available for the tuna larvae. Dr Mylonas explains that the same issue is preventing the uptake of farming technology for greater amberjack (Seriola dumerili), which was recently fine-tuned under the EU-funded DIVERSIFY project, which he managed. He believes the solution is to establish a tuna-only hatchery, and expresses some optimism by sharing that the current government in Greece is actively working towards opening up the aquaculture sector to create new opportunities and new jobs. Nevertheless, until that happens there is little hope of seeing progress in tuna farming in Greece.

© IEO

Update: Spain

In Spain, the Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO) operates a site in Mazarrón containing the only full-cycle tuna research facility in Europe, and Dr Aurelio Ortega is leading the research team. One of the projects is a unique tuna broodstock facility that started operating in 2017.

Dr Ortega explains that in June of this year his team are expecting their domesticated broodstock, which are now three to four years old and approaching 50kg, to initiate spawning. When this takes place it will be a significant milestone in the process of developing the European tuna farming sector, as up to now eggs have solely been obtained from tuna held in cages, an activity that is often disrupted by open-sea conditions.

Another major problem is that most egg batches obtained from the sea have a high inclusion rate of eggs of other species which, if they are faster growing than the tuna larvae, will feed on the juvenile tuna and decimate the production. Dr Chris Bridges, chief communications officer of TunaTech, who has been closely linked to the European tuna projects, also comments on the problem of exotic larvae predating on tuna larvae at the hatchery level. According to him, by moving their broodstock cages – which are located in Malta and owned by Malta Fish Farming (MFF) – 8km offshore, TunaTech have greatly reduced the inclusion of exotic species in batches of tuna eggs. On the other hand, their operational costs have gone up and his company is now far more dependent on good sea conditions for egg collection.

In recent years, some of the major players involved in developing full-cycle tuna in Spain have left the scene. Futuna Blue, which was setting up as a tuna hatchery in the south of Spain, has moved away and is now focused on seriola and sole. Futuna Mares from Norway has disappeared and Balfego from Cataluña is no longer involved. The Ricardo Fuentes group, which was a major industrial partner in the EU-funded projects, has also taken a back seat, although it maintains its interest and is likely to rejoin the effort once problems associated with the performance of hatchery-produced tuna have been resolved. For now there seems to be no commercial interest in starting a dedicated tuna hatchery.

With respect to current hatchery technology status, no one now doubts that the methodology for producing significant numbers of juvenile tuna is viable and reproducible. For Dr Ortega’s group the focus has shifted from quantity to quality, which is a positive perspective to take. He explains that, from his experience, it is the quality of hatchery-produced juveniles – in terms of growth and survival at sea – that needs improving. The IEO has been working with Piscifactorías Albaladejo through a project financed by the Spanish government, which was initiated in 2016. The project compared the performance in sea cages of hatchery-produced tuna juveniles with wild-caught juveniles. The main conclusion so far has been that the hatchery-produced fish are not as robust as wild-caught fish. Their growth rate was slow – only attaining 15kg in 2.5 years – and they experienced over 80 percent mortality during their first five months at sea. The researchers noted a variety of deficiencies with the juveniles, including malformations and visual-acuity problems. The fish also appeared to be very susceptible to pathogens and parasites. Both these factors are unacceptable from an industry perspective, and Dr Ortega is working with his group on improving juvenile quality further.

Update: Malta

Whereas in Spain the R&D activity continues, in Malta things seems to have come to a standstill. Dr Bridges mentions that the facilities where hatchery activities were once taking place have since closed due to a variety of reasons, some to do with Maltese politics. There is no other centre on the island that can carry out this type of work, nor will such a centre be available in the near future. Meanwhile Malta imports all the juveniles it requires for bream and bass farming and continues to catch wild tuna for fattening operations. Malta, with 12,500 tonnes wild-caught, ranched tuna produced on an annual basis, is in fact the largest producer of its kind in the Mediterranean. For TunaTech, the only business that they can continue with right now is the sale of eggs from the MFF broodstock to operators in Korea and the USA. TunaTech are also carrying out some interesting R&D in which they hatch tuna eggs in the vicinity of their cages and release the larvae into the wild. Using DNA fingerprinting methods they will be able to learn, in a few years’ time, if this helps to enhance the wild stocks.

The way forward

The only route to progress beyond this slump is through establishing a commercial tuna hatchery. Both Dr Mylonas and Dr Bridges see this as the motor that will drive the industry. Basically, to produce chicken you need the chicks. The Mediterranean bream and bass industry would not be where it is now had entrepreneurs not invested in the business of hatcheries, even though bream and bass technology at that time was far less developed than today’s tuna hatchery technology. Why is this not happening, and how can we get the tuna aquaculture sector in Europe moving again? This will be discussed in our next article.