Called ReShore, the company was established by Frej Gustafsson and Mitchell Williams in 2020, soon after graduating from Wageningen University with degrees in aquaculture and marine resource management respectively.

“Our plan was to create a business model for ecosystem services,” explains Gustafsson. “We’d had a couple of ideas. Initially we were looking into growing seaweed for carbon credits.”

That ran into obstacles – apparently their plan to give away any seaweed that was harvested was deemed to be illegal. However, their next idea involved coastal protection and they began to investigate the possibility of combining aquaculture with floating breakwaters.

“We realised that it was easier to sell the breakwaters as the primary product, and use the prospect of the ecological services delivered by the product as a bonus,” Gustafsson reflects. “Mangroves, corals and wetlands are natural breakwaters but they’re hard to sell, so we decided to look at selling grey-green infrastructure instead. This combines the reliability of engineering infrastructure with the benefits of nature.”

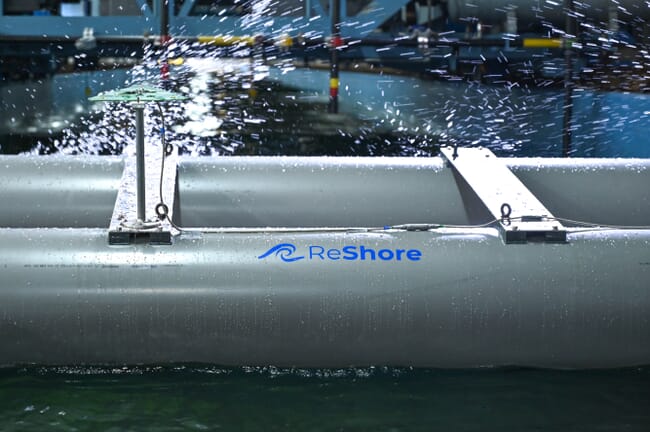

Their imaginations were fired by paper from researchers in Scotland which examined the use of a double pontoon to break waves.

“The double pontoon makes it more effective for protecting against large waves. Meanwhile aquaculture systems can be suspended underneath for aquaculture production, potentially even on a commercial scale,” Gustafsson explains.

While the concept is innovative, the duo decided against attempting to reinvent the wheel.

“We wanted to incorporate existing systems, such as oyster bags, seaweed lines or mussel ropes,” says Gustafsson.

They also plan to use steel and concrete as the main components of the pontoons themselves.

“These materials are reliable and safety comes first,” he notes.

Potential applications

Floating breakwaters are less common that fixed versions, but are becoming increasingly popular.

“Floating breakwaters are typically used in marinas and ports – some are on a very large scale, such as in Monaco, where the breakwater has a parking lot inside it,” notes Gustafsson.

“They are largely deployed in areas that are no longer protected by nature and are most effective in sheltered areas, rather than being used as the first line of defence against waves,” he adds.

In terms of integrating aquaculture into ReShore’s designs, Gustafsson notes that shellfish spat settle naturally on a range of structures, so there’s scope to combine the two with minimal effort. However, he also admits that it makes the most sense to focus on areas where there’s an existing shellfish farming sector.

“Shellfish can be grown anywhere but to do so on a commercial basis you need to have existing industrial infrastructure, so you don't have to start from the bottom up,” he notes.

However, Gustafsson adds that not all of those interested in the novel breakwater designs are seeking to harvest the shellfish or seaweed commercially.

"Many of the potential customers we’ve spoken to see aquaculture is a bonus, not as the core business – so harvesting the end products is not necessarily required,” he explains.

The company demonstrated proof of their design’s concept at Marin’s wave basin in the Netherlands last year. These trials have shown that combining mussels and breakwaters adds to the efficacy of the structures when it comes to reducing the impact of high seas, according to Gustafsson.

Funding and commercialisation

ReShore has been awarded a number of government grants and the commercialisation process has benefitted from the two founders taking part in the StartLife accelerator programme, which finished in December 2021. The company is now looking put a demonstration unit in the water this year and build their first commercial unit in 2023.

In terms of potential customers, Gustafsson reports good traction for their idea with harbours in several European countries, in areas that face increasingly regular storms and rising sea levels and have a need to improve their infrastructure.

“We offer an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional breakwaters. We can improve developers’ social licence to operate as well as help developments to be approved more easily by regulators,” says Gustafsson.

In order to install a pilot scale breakwater the company is now looking to raise “a bit north of €1 million”, but the cost to produce ReShore’s design is not significantly more than conventional breakwaters, according to Gustafsson.

Reaction from the industry

The company has had mixed feedback from existing aquaculture operators in the Netherlands.

“In the Netherlands, only a limited area is allocated for use in aquaculture, so some farmers are concerned that our breakwaters could reduce the areas where they are permitted to operate, but I don't think that would be the case,” says Gustafsson.

“Oyster farmers have been showing an interest in the design because the Dutch government wants them to move further offshore. What's more, producing oysters in high energy environment is good for the oyster growth,” he adds.

While the founders are armed with aquaculture qualifications, they are now looking to hire at least one person with an engineering background and are also open to working with partner organisations.

“We pride ourselves on good collaboration and have worked with the Dutch construction business, as well as the Marin research institute,” Gustafsson explains. "And we're actively looking for collaborators to continue to develop and realise our concept, both in terms of aquaculture and engineering. We'd love it if any interested parties got in touch via our website."

Gustafsson is convinced that projects such as ReShore’s – which capitalise on the ecosystem services provided by low trophic aquaculture species – are set to become more common.

“There is a change in the way aquaculture is seen and more people are exploring the potential for environmentally positive practices. The biggest driver is that people are really willing to pay more for sustainably produced seafood,” he concludes.