Given the scale of bivalve aquaculture globally, the benefits it provides to local economies cannot be overstated. And that’s before you consider the products that come from bivalve aquaculture, such as pearls, poultry feed grit and, of course, the food on our plate. But as Andrew van der Schatte Olivier, PhD student at Bangor University points out: “There is so much more to bivalve aquaculture than we currently think.”

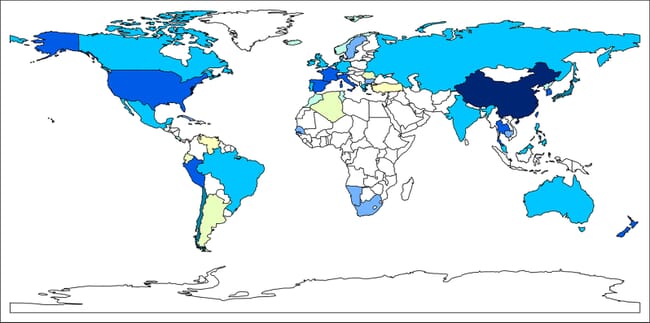

© Van der Schatte Olivier et al (2018)

Around 20 years ago, the concept of ecosystem services – “the benefits people obtain from ecosystems” – emerged as a way to aid sustainable development. In the language of ecosystem services, those products we gain directly from cultured bivalves are known as “provisioning services”. Alongside job creation and local economic benefits, provisioning services are typically what dominates policy and business discussions but considering ecosystem services requires us to look further. Which is why van der Schatte Olivier set out to uncover the other services bivalve aquaculture provides us.

There are three other types of ecosystem services aside from provisioning services. Underpinning all are what are known as “supporting services”. In bivalve aquaculture, these include nutrient cycling and providing habitat for other species. Then there are “regulating services”, which would include sediment movement and carbon storage. Finally, there are the less tangible “cultural services”, which range from recreational fishing to seafood festivals to spiritual and religious symbolism. If we were to put a global economic value on just the regulating and provisioning services, says van der Schatte Olivier, they could be estimated that to be worth around US$30 billion per year.

Whether planted reefs on the seabed or hanging from trestles, cultured bivalves will eventually be harvested and new ones planted in their place. While these short life cycles suit provisioning and some cultural services, supporting and regulating services arguably function better over longer periods. Throughout their short life, it is not uncommon for farmed bivalves to spawn and potentially seed reefs elsewhere, explains van der Schatte Olivier. If these reefs are left alone, either because they have not been discovered, have been protected, or are in an area that cannot easily be fished, then these offshoot reefs will grow naturally, providing, for example, more complex habitats that support diverse and stable communities of marine life – including commercially important species.

According to van der Schatte Olivier’s estimates, the bulk of bivalve aquaculture’s economic value comes from provisioning services (US$24 billion), but this does not mean that the other services are any less important. In fact, one of the most pressing issues of our time may also, in some way, benefit from one regulating service bivalve aquaculture can provide.

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report warns we have just 12 years to make drastic cuts to carbon dioxide emissions to limit global warming to 1.5°C and minimise the worst impacts of climate change on people, livelihoods and the environment. Alongside emission cuts, mitigation strategies such as carbon storage solutions also have a vital role to play in improving our future.

When carbon dioxide combines with dissolved calcium in the sea, it creates calcium carbonate – the main ingredient used by shellfish in building their shells. Although the shell-building process does release carbon dioxide, some becomes locked away in the carapace. The more bivalves there are, the theory goes, the more carbon will be stored in their shells and thus removed from the atmosphere.

Bivalve aquaculture is not the only form of aquaculture that has a potential part to play in carbon storage. Just like plants on land, seaweeds need carbon dioxide to grow and thrive. As a result, they store carbon within their tissues. When farmed seaweeds are taken out of the water intact, they take the carbon with them.

Farmed bivalves are also removed from the ocean whole, meaning the carbon locked inside them is also taken out. What happens to the carbon locked in farmed bivalves next depends on what happens to the shells. If the shells are ground up, van der Schatte Olivier notes, then the carbon will be quickly released. If they remain whole, then the carbon stays locked away – at least until natural breakdown occurs, which can take centuries. The question then becomes what to do with these whole shells. The answer, van der Schatte Olivier enthuses, may lay in part in reef restoration.

A good proportion of farmed bivalves go to the consumer whole. Once we have eaten the flesh, the shells end up in the bin, destined for a life in the landfill. Rather than sending shells to already overburdened landfills, some groups in the USA are using the waste to restore oyster reefs that have been destroyed. The idea is simple. Empty shells are collected from restaurants or donated by home-consumers, cleaned and carefully placed back in the sea. Whether pre-seeded with oyster larvae or not, these empty shells then form a base for live oysters to settle and grow.

Van der Schatte Olivier stresses that his values are estimates – and most likely underestimates – of the true value of bivalve aquaculture. While hard values for provisioning services tend to be well documented, supporting and regulating services are not something we currently pay for. Instead, we have to estimate what the cost would be if we were to do these things ourselves. Cultural services are even more difficult to value, due to their intangible nature.

“Cultural services are actually one of the most interesting aspects, but one that has been mostly ignored for a long time,” he says.

Indeed, the concept of giving such things an economic value can seem a little disingenuous, but for van der Schatte Olivier, it is important piece of the puzzle.

“When you are talking to policymakers and when people need to have debates, they need a common language. By giving this a financial value, at least it is in something we can discuss and compare,” he observes.

Perhaps van der Schatte Olivier’s work will help build a more accurate picture of the true weight of bivalve aquaculture in people’s lives – and its real contribution to economies, both micro and macro, around the world.

The full paper – A global review of the ecosystem services provided by bivalve aquaculture – can be read here.