Deep Bay is a shallow and narrow large bay, uniquely situated on the border between Hong Kong and Shenzhen, both mega-cities with millions of residents and home to global financial and tech giants.

© Kyle Oberman

Some may be curious why The Nature Conservancy (TNC), an environmental conservation organisation, chooses to work in the large cities of Hong Kong and Shenzhen; particularly in the practice of marine aquaculture. Both Hong Kong and Shenzhen are important parts of the Pearl River Delta – a place where the biodiversity-rich estuaries have supported the lives of the coastal communities for thousands of years, before the advent of industrialisation claimed much of the natural shorelines for development. This significant development resulted in substantial water-quality issues and pollution within Deep Bay – so much so that Shenzhen completely banned oyster aquaculture in Shenzhen Bay (the western half of Deep Bay) about 20 years ago.

However, the Chinese central government has been engaging in a re-strategising process and has a new focus on sustainable development – with ecological restoration and protection rising as a priority within its overall agenda. Hong Kong has shut down numerous pig farms and factories in order to reduce pollution into Deep Bay as well. Shenzhen and Hong Kong have established nature reserves on both sides of Deep Bay – Shenzhen Mangrove Nature Reserve and Mai Po Nature Reserve – to serve as sanctuaries for migratory birds and to preserve the remaining estuary habitats. The two cities have been carrying out joint water-quality monitoring in Deep Bay and the border river, which serves as a major freshwater input to Deep Bay, and engaging in training programmes and projects to improve the environmental integrity of the area.

For TNC, we see this as a great opportunity for not only oyster-reef restoration to bring back the natural reefs that were historically abundant here, but also for promoting restorative commercial aquaculture of bivalve shellfish, which has environmental, economic and social benefits. While Shenzhen banned oyster farming in the early 2000s, the Hong Kong Lau Fau Shan oyster farming community in east Deep Bay has continued their hundreds-of-years-old tradition, despite a sharp production decline and outside scepticism over the past few decades that the industry could survive.

© Kyle Oberman

Everyone who has the opportunity to visit this far north-west corner of Hong Kong is touched by how strong the oyster community’s culture remains today despite the challenges. Oysters are diligently planted, fattened, harvested, processed and finally sold on the wet market as a local delicacy, particularly for the Chinese New Year holidays. There is a special recipe for drying the oysters to make “golden oysters”, or Ho Si, Gum Ho (蠔豉、金蠔), which are not only traded as a food commodity, but also presented as a precious gift, even serving as a dowry in days gone by. Oyster culture is now officially listed as an intangible heritage in both Hong Kong and Shenzhen.

Not surprisingly, whenever there is a local seafood festival, the Chan family farmers are centre stage —this family comes from an oyster farming clan that has been living their oyster farming heritage for over 800 years since the Song dynasty in the 13th century. “We hope to carry on this livelihood, as it is part of our identity,” says Mr Shu-Fung Chan, the new chairman of the Deep Bay Oyster Cultivation Association (DBOCA). He is in his early 40s and ambitious, and wants to do things differently than how they were done in his parents’ generation. “We depend on a healthy bay that can bring about long-term economic prospects.”

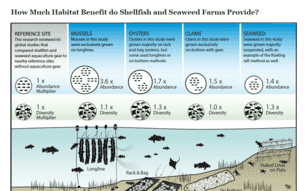

And helping to restore the health of Deep bay is exactly what TNC plans to do in collaboration with these farmers. TNC has worked in the United States, Belize, Indonesia, Palau and New Zealand to demonstrate that aquaculture and restoration can and should go hand in hand, to maximise economic livelihoods as well as environmental benefits, such as water filtration and biodiversity enhancement.

TNC has partnered with University of Hong Kong to study both oyster reefs and oyster aquaculture in Deep Bay – looking at biodiversity, habitat and water quality. We assessed the water-filtration rate of oysters in Deep Bay and found that an adult Hong Kong oyster (Crassostrea hongkongensis) can filter up to 30 litres of murky water in just an hour – a single oyster can clean a bathtub’s worth of water in Deep Bay in one day. While further research is needed, an ongoing hypothesis suggests that the presence of oyster aquaculture may be one of the main reasons few algae blooms have ever occurred in Deep Bay, despite the presence of significant agricultural pollution runoff (which has been linked to blooms in other bays).

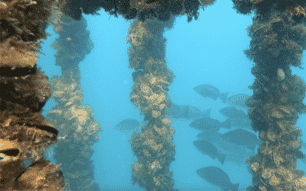

We are also assessing oyster reefs and farms for their role and value in habitat and biodiversity. After a year-and-a-half of monitoring a restored pilot reef and an experimental abandoned oyster farm, it’s clear that the reef structure is critical to increasing species numbers and diversity along the shoreline of Deep Bay, particularly crustaceans. This finding resembles a success story in the Chesapeake Bay, where oyster restoration and aquaculture may be contributing to the rebuilding of the locally important blue crabs.

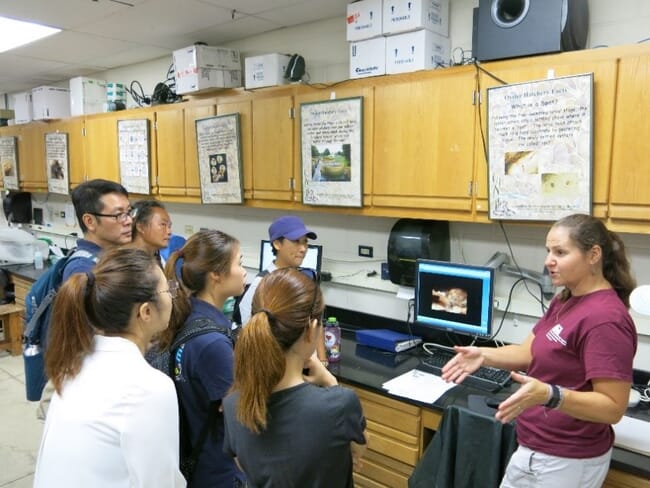

In fact, TNC was able to bring the Hong Kong and Chesapeake Bay oyster-restoration and aquaculture communities together for a knowledge exchange in September 2019. TNC invited the Lau Fau Shan oyster farming representatives, government officials in fisheries management and academic and NGO allies to take part in a week-long study tour to the United States, where we highlighted restorative aquaculture and reef-restoration research and partnerships. Highlights included discussing policy with officials from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in Washington; visiting Horn Point Laboratory and Hoopers Island Oyster Co to learn hatchery and farming techniques; and staying at the TNC Virginia Coast Reserve to see established oyster restoration in action. The invitees were inspired to develop a shared vision for oyster aquaculture back home that revives the industry, restores the natural environment and the preserves cultural heritage.

© Lulu Zhou

Looking ahead, there are still a number of challenges that need to be addressed. The number of floating oyster rafts is on the rise – an estimated 10,000 now crowd the Hong Kong half of the Bay – and oyster yields have declined in recent years. Along with our partners, we plan to conduct a carrying-capacity assessment of Deep Bay to gain an understanding of how aquaculture practices should be optimised. We will work with farmers to develop better management-practices guidelines that incorporate site selection, modernisation of aquaculture gear and operations and environmental monitoring.

In addition, we plan to develop policy recommendations on a permit and compensation scheme to safeguard farmers’ rights and access to government aid when there are unpredictable situations (such as typhoon damage or a public-health issue like the current COVID-19 outbreak) that have the potential to negatively impact production or sales in the industry.

Hong Kong and Shenzhen have previously served as a window to the world, demonstrating how China has developed its economy. Can these two cities now serve as a model globally in a different way, to show that a modern, profitable and restorative aquaculture industry can be possible, and that it can work in tandem with oyster-restoration efforts to create a healthy bay and people? We believe we can help this vision come true – after all, the world we depend on depends on us.