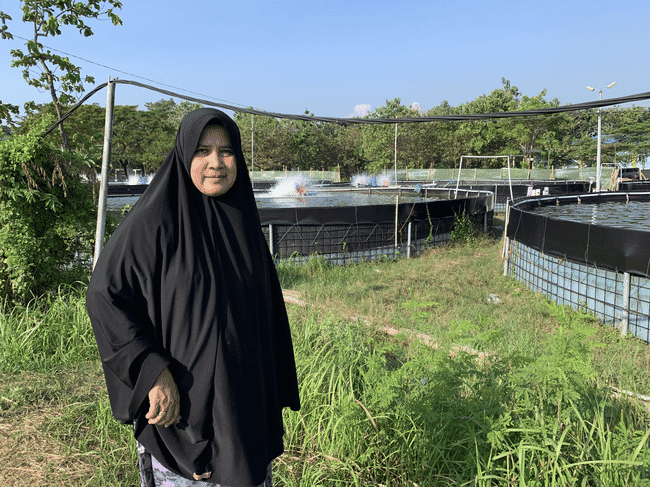

Asiyah started her own shrimp business in 1998

Briefly describe your aquaculture career

In 1989, after graduating from the Semarang Farming College (Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Pertanian Farming Semarang), I migrated to Lampung to work for the Gajah Tunggal company’s shrimp hatchery division. After a few years, I moved to Central Pertiwi Bahari. I spent a total of about nine years in the two companies.

In 1998, after having two children, I resigned and started my own business. My colleagues and I opened a mini hatchery in Lampung and rented a hatchery in Anyer, West Java. I also started cultivating shrimp in Lampung, although only for two years. At that time, the sector was still dominated by black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon). I marketed my shrimp post-larvae (PL) to farmers on the southern coast of Java, especially Purworejo and Kulonprogo.

In 2005 I was inspired to start a shrimp farm again with my colleagues, in Purworejo, mainly cultivating Pacific whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) in 11 ponds. Apart from shrimp production, the farm was also a showcase for the PL produced by the Anyer and Lampung hatcheries. In its heyday, the Lampung hatchery could produce 30 million PL and the Anyer hatchery 60 million PL per cycle. I also opened a shop in Purworejo which sells products such as lime, disinfectant and probiotics. However, I discontinued both the Lampung and Anyer hatcheries. First, the rising sea level slowly destroyed the facility in Lampung. Second, I no longer have the capacity to travel back and forth, as it is quite far away from my home in Semarang. Meanwhile I had to close down the farm in Purworejo, due to the change in local agrarian regulations a couple years ago.

Asiyah currently runs a shrimp hatchery and grow-out farm in Jepara, Central Java

While still running the shop in Purworejo, I currently focus on running a shrimp hatchery and grow-out farm in Jepara, Central Java which have been running since 2018. The farm and hatchery facilities that I manage are not only commercial, but also educational. We host many students who want to learn more about aquaculture. Jepara is also a good location for me because it is a lot closer to my home in Semarang.

How is your current farm and hatchery productivity?

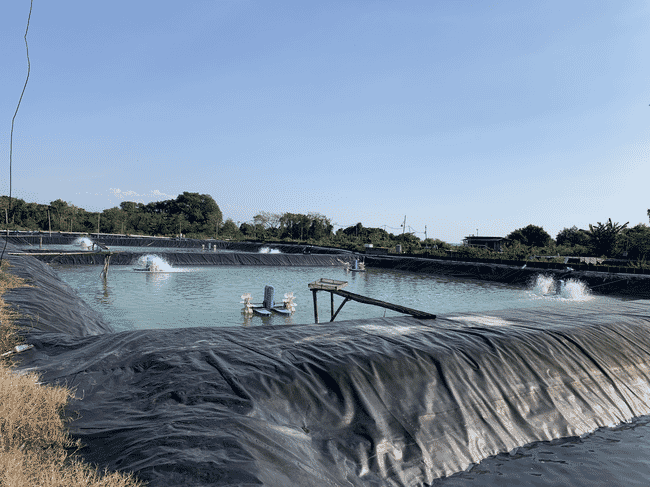

For the farm, I manage eight HDPE-lined square ponds, each with an area of 625 m2. They are relatively small in size compared to most ponds, which are usually more than 1000 m2. The farm has been operating for 11 cycles. The highest total yield in a cycle was 18 tonnes – the equivalent of 36 tonnes per hectare.

Currently, I am also trying to develop 16 metre diameter circular ponds. We have 16 of these which have been running for three cycles. Productivity per pond, per cycle can reach 1 to 1.5 tonnes – the equivalent of about 50 to 75 tonnes per hectare.

The highest total yield on Asiyah's farm in a cycle was 18 tonnes – the equivalent of 36 tonnes per hectare

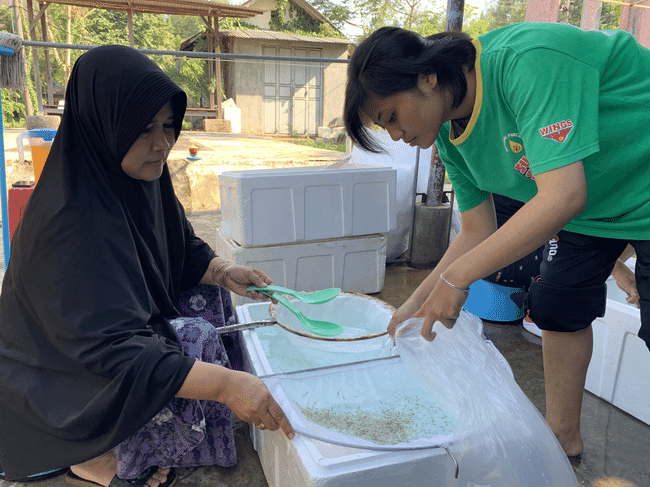

For the hatchery, the current production capacity can reach 15 to 20 million PL per cycle. From the nauplii stage to PL10 it takes 18 to 20 days – much faster than shrimp grow-out, which takes 90 to 120 days. However, in the hatchery business, the competition is very tight.

What drew you to aquaculture?

After university, I worked for one of the largest shrimp farming companies at that time and I felt that this industry could lead me to a better financial situation. Seeing the success of the company motivated me to have my own aquaculture business. Finally, I am fortunate enough to have my own small farm and my small hatchery. I’m still happy with the business and I even found the love of my life in aquaculture. My daughter also studied aquaculture in university too.

Asiyah's day consists of managing employees, monitoring lab conditions, monitoring water quality conditions and ensuring SOPs are carried out properly

What does a typical day consist of for you?

I used to be very hands on. I like to take care of all things by myself, from the hatchery side, to the farm and the shop. Even though I'm a woman who wears a hijab, I was always ready to get my hands dirty. But recently, because of my age, I took a step back and handle only general matters, such as managing employees, monitoring lab conditions, monitoring water quality conditions and ensuring SOPs are carried out properly.

Beyond that, I participate in many aquaculture events, and focus on motivating the younger generation, giving them the drive to keep on developing themselves.

What are the challenges you face in your field?

There are so many diseases that come and go. That's what makes me anxious most of the time. However, my husband always reminds me to stay calm. There are always ways to overcome them.

On the hatchery side, the toughest challenge is competition in the market. There are so many hatcheries out there, both small and large, so we have to be smart in looking for opportunities and implement the best strategies to market our PL.

The specific challenge in the Jepara region is that the water in the bay area was considered unsuitable for cultivation and the salinity is quite low in the rainy season. However, after experimenting with the local conditions, we have been able to produce good PL and grow shrimp.

Having said that, I always continue to study the environmental conditions here. Just because I've succeeded before, doesn't mean that I will definitely succeed again. Shrimp farming is very dynamic and it needs continuous research.

One key challenge in the Jepara region is that the water in the bay area was considered unsuitable for cultivation

Have you encountered any gender-related challenges in the sector?

In the 1980s and '90s, women's roles were generally limited to quality control. Women could not become technicians or play a key role in managing hatchery and pond operations. That is because the job requires 24 hours commitment and the work load involves heavy manual labour, which was deemed unsuitable for women. But it's changing now, women can do a lot more things.

As a woman doing business in aquaculture, I feel that there are no particular problems. Maybe because I'm confident with myself. Even when there are people saying something negative about me because I'm a woman and I do business, I don't pay them any attention. I just enjoy doing what I am doing.

What work-related achievement are you most proud of?

A few cycles ago our farm was able to produce up to 36 tonnes of shrimp per hectare and I am very happy with that result. However, I could not be prouder than when students who used to intern or work with me achieve their own success. For example, a student of mine opened 20 ponds in Kendari; some work as civil servants in the Fisheries Agency; and many become technicians in various farms across Indonesia. Their success makes me feel happy and proud too.

Asiyah has taken on many students and interns who have gone on to be successful in the shrimp industry

What is your favourite part of working in aquaculture?

Every part of it is fun, whether it is in a hatchery or grow-out. Sometimes I feel anxious that my business will go bust, but I always remind myself that my intention is to create jobs and to help many people. That is what keeps me motivated.

I'm also happy to be part of a community of great people. We can exchange information and support each other.

Are there any individuals or organisations that you've found particularly inspirational?

I am inspired by all the women I meet in this field. I remember a female hatchery technician named Emi who, at the age of almost 60 years, is still actively involved in the field, getting her hands and feet dirty. In the past, I was also inspired by my colleagues, women from the Jakarta Fisheries University who were dashing and very disciplined in their work. I was also inspired by Susi Pudjiastuti, Minister of Marine Affairs and Fisheries from 2014 to 2019, who showed that women can also have an active role at the forefront of things.

Asiyah hopes that Indonesia's shrimp sector can find effective solutions for disease outbreaks

What advice would you give to women who are considering working in aquaculture?

There are no limitations for women to be involved in shrimp farms or hatcheries. Now I see many young women who are actively involved in the farming operations. They are not afraid to get in the ponds and get their hands dirty. I am very proud to see it. Some even told me that they wanted to open their own business in the future. That should be encouraged by all parties. At this time, we need regeneration and the more women are involved, the better.

What are your hopes for the Indonesian aquaculture industry in the future?

We hope that together we can tackle one of the biggest problems in aquaculture, namely disease. We are still looking for a solution. Meanwhile, the best step that can be taken is disease prevention. Even so, I remain optimistic about the future of Indonesian aquaculture because there is still a lot of potential, which needs to be developed properly in the future.

One of the many ways the Indonesian government could also support the growth of aquaculture is by creating easier ways for farmers to get their farming permits. The government could also support us by importing high quality shrimp broodstock and, to some extent, help with price stability.

In addition, I also hope the Indonesian government could develop a plan in which tourism and aquaculture could grow in synergy. Sometimes farmers have to shut down their operations because the coastal area is going to be designated as tourism spot. While tourism is good for the economy, it is better if both could co-exist to encourage Indonesia's economic growth.