Can you briefly describe your aquaculture career?

The first time I got involved with it was in 2018. At that time, I was still an undergraduate student at Gadjah Mada University (UGM) studying management. Fajar Sidik Abdullah Kelana, the founder of Banoo, approached me to join him in developing an idea in aquaculture.

He had already developed Mino, an aeration technology for maintaining water quality. He came from an engineering background. He studied mechanical engineering at UGM and he needed someone to deal with the business side. I thought it was a great opportunity for me to learn more about business development.

We then set up a four-person team to focus on developing the idea for research and competitions. We joined the Cisco Global Problem Solver Challenge in 2019 and won the People’s Choice Award. In 2020, we became a finalist at the MIT Solve Sustainable Food Systems Challenge and also won the Grand Prize at the Thought for Food Challenge.

Before Covid-19, we planned to do market research, but then decided to join an accelerator. In 2021, we continued to do a product-market fit. Since September 2021, I’ve been studying for a master’s in innovation, entrepreneurship and management at Imperial College London. So, now I work remotely but my team are working on-site to continue the research.

Shafira and her colleagues have competed in and won multiple international innovation contests

Can you summarise the solution you developed with Banoo?

We have so far focused on developing products for freshwater fish farmers. The solutions we develop focus on water quality, through aeration, automation, and monitoring. The product that is currently being launched is Mycrofish, which is an aeration technology that farmers are starting to buy. Mycrofish uses microbubble technology because it is affordable and simple compared to nanobubble, which has a fairly complex system and complicated installation.

Our aeration technology allows oxygen to spread to the pond bottom. This technology could allow farmers to stock at higher densities while maintaining good oxygen levels. Our technology is really simple and could be installed by farmers themselves. So far, Mycrofish is used by tilapia and catfish farmers in Yogyakarta, Central Java and West Java. We are focusing on scaling up Mycrofish while developing other products.

How do you differentiate your products from those of competitors in the market?

Our main value is to be farmer friendly. We do not want to develop technology that is difficult for farmers to operate. Our vision is not only to provide tools, but also to focus on farmers' experience with our tools. We want to create new habits for farmers, so they can become more efficient and agile.

Mycrofish uses microbubbles to evenly and automatically increase dissolved oxygen levels in ponds

In this case, automation is important to facilitate the adoption of the technology. In Indonesia the sun provides enough energy for photosynthesis by algae in the water during the day. During the afternoon until the evening oxygen levels begin to decrease, as the algae respire. If dissolved oxygen (DO) levels drop at 4 pm, for instance, the farmer does not need to turn on Mycrofish manually because it will turn on automatically.

We also use sensors because we want more precision. Farmers do not need to go to the pond to monitor it. With real-time data, they can understand their pond condition and predict future events. Troubleshooting can be done immediately, to reduce the risk of crop failure.

What drew you to aquaculture in the first place?

I have always been interested in food technology. I have lived around rice fields since I was little. My neighbours are rice farmers, so I understand their life from an economic and social perspective. My parents also used to farm catfish, although they did not continue that business. People in general think that farming catfish or tilapia is relatively easy, but, in reality, it is not. It is quite risky and highly dependent on the environment. Most are also farming using traditional methods.

We at Banoo do not want farmers to rely on traditional methods. We want to develop technology to make aquaculture production more efficient. The more I talked with farmers, the more I realised that they are actually waiting for people who can provide the technology for them. From that observation, I saw and understood the real problem and the opportunity too.

Now I am convinced that I will continue on this path. We want to develop technology that can be used by farmers and sustained through time.

How do you see Banoo evolving in the years to come?

Now the climate is unpredictable and we cannot depend on traditional methods. Banoo wants to equip farmers with tools that could help them and become their friends. Learning from previous cases, the adoption of technology has not been successful because there was a lack of assistance or that the value of the technology was not clear enough for farmers. We want to avoid that.

We are now focusing on conversing with farmers to understand their situation, needs and problems. How we evolve is by listening to them. Then, we will develop Banoo based on the conditions and opportunities that exist. So, we can grow with them.

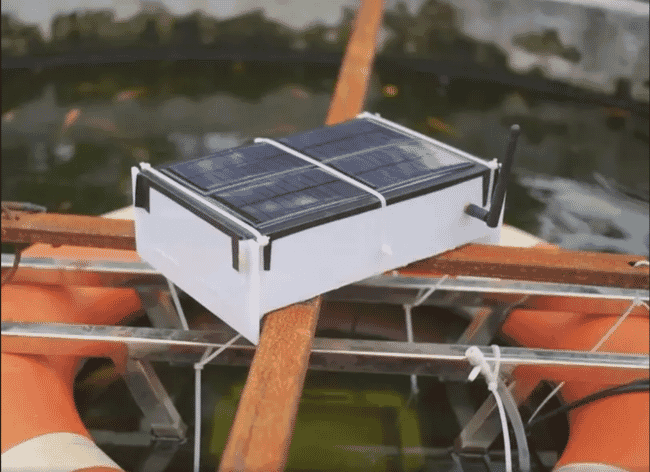

Fisko is an automated and solar-powered sensor that monitors pond conditions

As someone with a background outside of aquaculture, I also want Banoo to be more inclusive, not just for those with aquaculture background. We also want more women to involved in aquaculture. Many of my female friends are interested in the aquaculture industry but are reluctant because they think that this industry is only for men.

I want to dispel that stereotype, that this is an industry exclusively for men. Everyone can be involved in many ways. Being a farmer is also something cool. With a lot of technology being developed in Indonesia, we could make this industry more inclusive in terms of gender, generations, economic backgrounds and education.

What work-related achievement are you most proud of?

When Banoo won the Grand Prize in the Thought for Food Challenge. We pitched in, followed the accelerator programme for almost a year, and we did it all during Covid-19. When the winners were announced, we were very happy and felt that this was a positive sign for us to continue our mission.

When we feel down, we always go back to that time. Those memories make us proud. That moment also became an eye-opener for me that my task was not finished. My work will not be finished until the impact of Banoo is felt by farmers in Indonesia and other countries.

Banoo tested their Mycrofish aerators on different farm sites in Indonesia

What challenges have you encountered in your career?

Approaching and starting discussions with farmers takes a long time. We had to knock on the farmers' doors and get our feet to the pond. Meanwhile, our team are still very young and limited in number, so approaching farmers became a challenge for us. Sometimes we are rejected, sometimes we are welcomed. We studied quite a long time to understand how they operate.

The next challenge is to translate the results of the discussions with farmers into a new technology. We need mentoring, participation in competitions and accelerators to validate our product, so that we can make useful technology. We want to make the being farmer-friendly not only a tagline, but also something visible in practice.

Have you faced any particular challenges as a woman in aquaculture, particularly now you're a CEO?

As a CEO, I did not feel this way at first, but now I feel it quite strongly. What my mentor said stuck with me, that women founders are overmentored and underfunded. I noticed that I had a lot of mentors, both personally and for Banoo. After I educated myself by reading a lot of literature in the topic, many indicated that a gender-bias in women's startups funding does still exist.

Currently I am joining an accelerator for women-led startups at Imperial College called WE Innovate and I see the difference from conventional accelerators. I feel that they are more supportive of me and see me from the business idea that I bring, instead of questioning me about non-business related issues.

In other cases, I have experienced being questioned about my marriage status, whether I would stay at Banoo or live with my husband after marriage because maybe they see me as a women founder with Asian background. I do not think that similar questions were asked to male founders.

Are there any individuals or organisations that you’ve found particularly inspirational?

I look up to eFishery and their CEO, Gibran Huzaifah. I often ask Gibran for his input and he is very open in the midst of his busy time. eFishery is also now sort of the north-star of aquaculture startup in Indonesia. When I had a pitching session with a VC from Silicon Valley, they asked me about eFishery. So, they are a very well-known company.

That makes me confident and optimistic, as a businesswoman, that aquaculture startups have the potential to become a sustainable and profitable business. We are both providing technology and we want to be able to grow as big as eFishery.

"I really like to learn new things and, at Banoo, there is no day without learning new things, because the industry is very dynamic."

What do you like about working in aquaculture?

First, this job is not quite mainstream, not something my friends and family would expect me to be doing, so defying their expectations is fun. I also really like to learn new things and, at Banoo, there is no day without learning new things, because the industry is very dynamic. There are new developments every day. Problems pop up every day as well. Problems are always going to be there, but that is what keeps me interested.

In my opinion, aquaculture is an industry that is in the stage of revolution and I am quite proud and happy to be able to be a part of that revolution. I also want to solve the challenges in aquaculture. That is why I want to remain in the sector.

What’s the most unusual experience you’ve had in aquaculture?

When we did our research, we rented a catfish farm to test our tools. Then one day when we checked the pond, it turned out that the catfish had been stolen. At that point, I just found out that such issue does exist. Surprisingly, though, while the catfish was stolen, our tools were intact.

It is a field experience that is hard to find anywhere else. From that experience, I understand what goes on behind the scenes of fish farming. I understand why farmers are very apprehensive of new people who want to come to their farm. We gained a valuable perspective on how to approach farmers.

How do you see the future of aquaculture in Indonesia?

I am quite optimistic. I think that with many aquaculture startups such as eFishery, Jala and FishLog, people are realising the potential of the aquaculture industry. With their development, exposure to various media, and the funding they get, more and more people are interested in working in aquaculture. Many of my friends are also interested to join the Banoo team because they see that this industry has a future. This means that public trust is increasing.

The government also helps with various programmes that are focused on aquaculture. This makes me even more optimistic that aquaculture will be at the forefront of food security in Indonesia, instead of relying too much on capture fisheries, which are currently dropping in productivity. This is an opportunity for aquaculture to become a source of fish production in Indonesia and the world. I envision aquaculture becoming Indonesia's favourite industry.

If you could solve one issue in aquaculture, what would it be?

The issue of access. For instance, in regards with Banoo, can our technology be used in rural areas? How can we provide IoT technology if there is no internet connection? Even the electricity infrastructure in Indonesia is not reliable, especially in rural areas. That is what I want to solve: giving technology access to rural farmers.

What would you like to be doing in 10 years’ time?

I really want to stay at Banoo, because this is just the beginning. In 10 years, our mission might not even be finished. I personally have no plans for a career elsewhere. Nothing is stopping me from staying here.

My big vision is for Indonesian aquaculture to have a healthy ecosystem in which all stakeholders – including industry, academia, government and the people – work in synergy. We all should be in partnership with each other to encourage innovation.