The startup plans to try and improve biodiversity within wind farms through farming seaweed

Can you tell me a bit about your background?

I grew up in and around the offshore industry, my dad worked as a deep-sea diver and I was brought up in Plymouth, so I guess as I’ve always been predisposed to work in the marine environment.

I’ve spent the past 17 years as a subsea engineer, initially in oil and gas, then 13 years working in offshore wind on the installation and repair of export and array cables for companies including Centrica Renewables, Ørsted and Macquarie. The wind industry has changed significantly since I first started, for the better, and it’s great to see some of the leading firms starting to seriously look at incorporating nature-inclusive designs within their wind farms. This shift towards improving biodiversity presents an interesting opportunity for Cultivocean, our partners and local communities.

What inspired you to found a startup in the seaweed space?

I joined a venture builder called Carbon13 that brings together people with varied backgrounds, knowledge and experience with the ambition of forming startups that have the potential to remove 10 million tonnes of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions per year when fully scaled.

I initially entered Carbon13 looking to use seaweed to reduce scour around subsea structures and minimise coastal erosion. That subsequently evolved as we began further research into the benefits and uses of seaweed. There are a number of progressive companies working in this space here in the UK, including the bioplastics firms Notpla, Kelpi and PlantSea. But, in order for these companies to grow, there needs to be an established supply of local, sustainably-sourced feedstock.

The startup believes that the real benefits of farmed seaweed are in replacing high carbon products – petrochemicals in plastics; man-made chemicals in fertilisers; or as a meat substitute. © Cultivocean

What’s your basic business model?

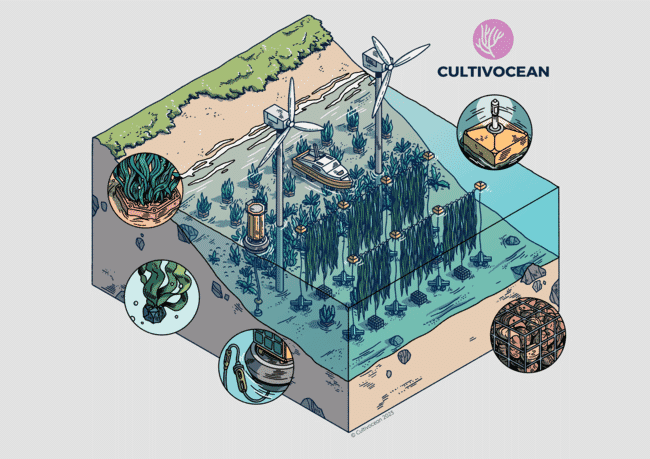

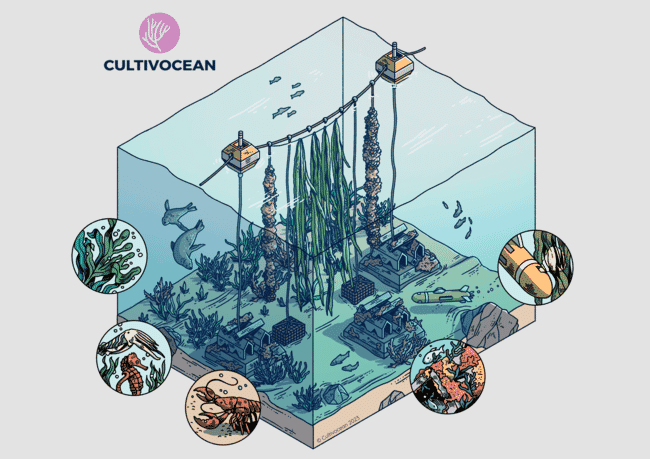

We plan to improve biodiversity within wind farms and, as part of the design, we’ll incorporate anchor points that enable seaweed farming to scale quickly, in-line with market demand.

We’re at a point in time where larger companies have the potential to develop innovative products using macroalgae (seaweed) but are refraining from doing so because the supply of feedstock isn’t there. Our solution reduces the time lag between demand and supply. We really need to be giving industry confidence that the seaweed market in the UK can provide suitable quantities of seaweed without having to rely on imports from Asia. It somewhat defeats the purpose of companies developing products like eco-friendly bioplastics if we need to import the raw materials and account for the GHG emissions from the transport of them. This is particularly frustrating when you consider the UK is an island with ample marine resources, knowledge and experience that can be utilised to re-establish a thriving seaweed industry.

The nature-based element of the design will be adapted, depending on the water depth and environmental conditions on site, and can vary from the installation of a seagrass meadow in shallower waters through to rewilding kelp forests, to the installation of artificial reefs. It’s important to us to maximise the use of space at the project sites to ensure we’re having the most impact, whether that is from cultivating seaweed, enabling multi-trophic aquaculture, or creating a haven for juvenile fish to help re-establish fish stocks.

I think it’s also important to clarify that we won’t be looking at blue carbon credits from cultivated seaweed. There are a lot of overly positive claims regarding the benefits of seaweeds, but these should be taken with a pinch of salt, especially regarding the potential to farm seaweeds with the sole purpose of carbon removal, as the science behind this isn’t fully developed. The real benefits of farmed seaweed are in replacing high carbon products – petrochemicals in plastics; man-made chemicals in fertilisers; or as a meat substitute.

What makes you unique?

Our experience and knowledge of installation, operations and maintenance within offshore wind farms enables us to develop best practice procedures and risk assessments that help to open access to these sites, whilst minimising risks to the export of renewable energy. Part of what we’re doing will require us to work collaboratively with experts from academia, wind farm operators, and local fishing communities to utilise their knowledge, vessels and skills to cultivate and harvest seaweed.

What feedback have you had from the offshore renewables and seaweed farming sectors to date?

All the conversations we’ve had across industry have been positive, but – like anything new – there are challenges that need to be solved. We recognise that the primary purpose of these sites is to generate and export clean energy and this has heavily influenced our design to the point that we essentially want to co-habit the space with little or no interaction with the wind farm itself. That also extends to the wind farm operator, in that we don’t want to impede their work, so it is essential that the designs for their sites work for them and we build in exclusion zones around their assets that account for jack-up footprints, cable repair scenarios, and incorporate transit corridors within the site.

What are the major obstacles to overcome to make the business viable?

We have organisations like The Crown Estate and WWF looking at marine spatial planning which will be critical to improving biodiversity in the already congested marine environment. This is where co-location of seaweed cultivation within wind farms will make better use of the space, whilst bringing in alternative revenue streams for local fishing communities and decarbonising the UK economy. We need to take a collaborative approach to nature-based solutions that isn’t currently being done.

The licencing process needs to be streamlined as it’s a big hurdle to further participation in this space, both from a cost and time perspective. This is made more challenging by having to align with multiple organisations, all of which have slightly differing views on how they plan to achieve biodiversity and net zero targets by 2030. There are positive signs that this is changing, but it’s critical this is done in a timely manner to allow sufficient time to trial and scale these nature-based solutions.

Approximately 12,000 km2 of seabed is currently used for offshore wind in the UK © Cultivocean

How are you funded/are you looking to raise more funding?

Cultivocean is privately funded and as we grow there will be a need for additional finance to really achieve the scale of projects we need to meet net zero and biodiversity targets. That external finance could be from a few sources such as wind farm operators, venture capital, NGOs and grant funding.

We also have a few applications for grant funding that will help us to progress some key aspects of the design if we’re successful.

And, as with any form of farming, seaweed cultivation requires a lot of capital expenditure and risk in terms of losing crops to disease or because of adverse weather conditions. With small margins it really needs Government input to help establish the industry the same way they helped offshore wind with large subsidies. Now we can see the benefits of that investment and there is no reason we can’t see similar levels of progress with co-location or multi-use projects such as ours, especially when you consider there is approximately 12,000 km2 of seabed used for offshore wind in the UK that can be better utilised to help solve some of the climate challenges we face.

How do you see the company evolving?

There is a certain amount of inertia we need to overcome to get trials in the water before we even get to a scaled solution.

The positive thing is that we’re starting to have conversations with key organisations and companies where this wouldn’t have been the case a few years ago. Collectively, the danger we face is thinking that time is on our side when we have net zero and biodiversity goals on the horizon. This kind of trial infrastructure takes time: from the initial planning phase; to licensing; then installation; and ongoing monitoring taking around 6-years. And that’s assuming you’re successful in each phase of that process. Then, and only then, can we look at really scaling this opportunity.

We’re finding ourselves in a precarious situation and this is where we need to see industry and government organisations be brave and make scaling nature-based solutions a reality.

There are a few queries/questions that cannot be answered, as the data aren’t there to make a scientific assessment, but that shouldn’t prevent action being taken and we’re seeing this echoed by organisations such as The Crown Estate, Natural England, Cefas, WWF, The Wildlife Trust and many others.

There’s a lot of work ahead to make the changes we need and that involves working with fishing communities (and the wider community) to establish a thriving industry that brings jobs and finance to the local area. The most important thing is that we start.