The UK's native oyster populations have decreased by 95 percent since the mid-1800s due to overfishing

Data from the Environment Agency shows that native oyster populations have decreased by 95 percent in England since the mid-1800s, mainly due to over-fishing. The aim is to reverse this decline because oyster reefs bring multiple benefits, including cleansing seawater through filtration and increasing biodiversity and fish abundance.

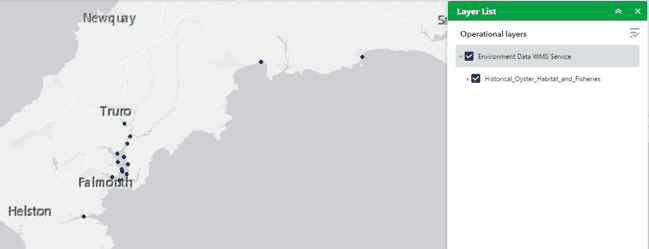

Developed by academics from the University of Exeter and the University of Edinburgh for the agency, the new map data layer is on the ArcGIS (geographical information service) site and provides information on the location of historic native oyster records and distributions.

It will also sit on the Coastal Data Explorer, which is a public web mapping portal managed by the Catchment Based Approach initiative.

It can act as a tool to support local authorities, community partnerships and environmental organisations to make the case for native oyster restoration projects, one of the three estuarine and coastal habitats that are the focus of the Restoring Meadows, Marsh and Reef (ReMeMaRe) habitat restoration partnership project.

The data is available on the ArcGIS (geographical information service) site and provides information on the location of historic native oyster records and distributions

The layer works alongside the Environment Agency’s Native Oyster Restoration Potential maps that highlight areas where oyster restoration could be successful, and the UK & Ireland Native Oyster Network and Environment Agency’s European Native Oyster Habitat Restoration Handbook that provides guidelines on how to restore these valuable habitats.

The handbooks and maps aim to counter the huge loss in native oyster reefs over the last two centuries by encouraging and supporting new restoration projects.

The map layer was created using data from government, and scientific and maritime bodies, and historic media accounts that mention the use and presence of the native oyster, Ostrea edulis, across England.

Environment Agency estuary and coast planning manager Roger Proudfoot said, “the release of this information on where native oyster reefs were once present represents another milestone in our drive for more estuary and coast habitat restoration.”

“We have lost 95 percent of our native oysters mainly due to over-fishing. As well as being catastrophic for our marine ecosystem, we have also lost the multiple benefits that they once provided for us, including cleansing our waters through filtration and increasing biodiversity and fisheries.”

“We hope this new information on the historic locations of once thriving oyster reefs will lead to new opportunities for restoring what has been lost. We know that oyster restoration is possible, we just need more capacity to upscale the current efforts and we look forward to this new information inspiring more projects to restore this magnificent mollusc.”

Dr Ruth Thurstan, project lead and senior lecturer at the University of Exeter said, “oysters once formed an understated but important part of British marine ecosystems and popular culture. In the 19th century we fished and consumed oysters by the millions, while their complex reef habitats were key to supporting other marine life that we valued and depended upon.

“Much of this was lost as oyster habitats declined, and our marine ecosystems today are fundamentally different. This map of historical oyster fisheries is a step towards building the knowledge base required for successfully restoring this culturally and ecologically important species in our coastal waters.”

Further details of native oyster restoration efforts can be found on the Native Oyster Restoration Alliance website.