© Dr Bill Walton, VMS

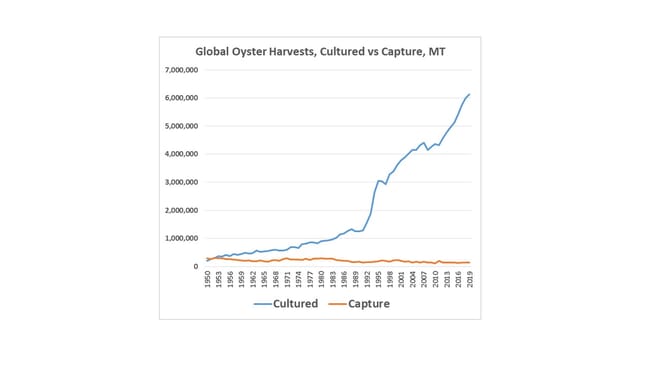

When many people think of oysters they envision a cluster of odd-shaped, rock-like objects, typically growing on some hard surface on or near the seafloor. According to FAO figures, in 1952 global oyster aquaculture production surpassed wild harvests for the first time – with 306,930 and 302,526 tonnes reported, respectively. Aquaculture production has consistently exceeded wild oyster harvests since that time, and in 2019 accounted for 6,125,606 tonnes, compared to 133,984 tonnes of wild-harvested. Traditional culture methods relied (and still rely, in many regions) on natural setting of wild larvae on suitable benthic substrates. But there are other ways to grow oysters, and these techniques can result in significantly greater production volumes.

Off-bottom oyster culture utilises trays, baskets, cages, or hanging lines/ropes mounted on racks or suspended from floats or rafts. This approach allows for more access to natural foods and avoidance of many fouling organisms and predators. Fouling organisms still occur, but one remedy that can be adopted in off-bottom culture involves regular exposure of oysters to the air (weekly or biweekly), in such a way as to inhibit growth and survival of fouling organisms, while oysters close their shells and wait patiently until they are re-submerged.

The early days of off-bottom oysters

To be clear, while it is still a novel concept in Louisiana, off-bottom oyster culture is nothing new. Techniques were already being developed in several countries almost a century ago. While on-bottom culture was the universal method for oyster production in Japan in the mid-1920s, for example, by 1960 the industry had shifted almost entirely to off-bottom techniques and long-line methods were already widely in use in Japan during the 1940s.

In North America methods for off-bottom collection of seed oysters and subsequent growth prior to planting on water bottoms were first developed at the Biological Station in Ellerslie, Prince Edward Island in the 1930s. Two decades later the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries began evaluating the potential for off-bottom oyster culture in Massachusetts. In 1969, WN Shaw with the Bureau’s Biological Laboratory in Maryland presented a review of North American off-bottom oyster culture. Although at the time most off-bottom activities centered around the collection of wild seed as they settled on shells hanging from rafts or racks in the water column, several small operations were also rearing oysters all the way to market size in a similar manner.

A number of research and commercial off-bottom initiatives in the US were described by Shaw, in locations ranging from Florida to British Columbia and Massachusetts to California. In what Shaw cited as the largest commercial off-bottom operation on the east coast at the time, a 20-acre salt pond in Fishers Island, New York was outfitted in 1968 with 55,000 strings of scallop shells suspended from 130 floating rafts to collect oyster spat. Estimated harvests were approximately 25 million eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) seed. More than a decade earlier, some 200,000 strings with shells were hung for the first time from floats and rack structures in Debob Bay, Washington, to collect Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) seed, but results there were notably inconsistent from one year to the next.

Off-bottom culture methods at the time of Shaw’s review were plagued by severe weather events, sedimentation, fouling organisms (which, once established, interfered with or prevented setting), and predation from various species. These constraints still impact off-bottom growers to varying degrees in most regions, especially in the warm, fertile waters of the northern Gulf of Mexico. Nonetheless, a number of studies in various locations had demonstrated by the 1960s that off-bottom oysters could grow 1.5 to 2 times faster than their counterparts planted on water bottoms under optimum conditions. Shaw was careful to point out a number of potential constraints to expansion, however, including conflicts with recreational users and navigation, as well as the need for regulatory and policy changes to accommodate new harvesting methods.

The Louisiana technique

While innovative methods of oyster culture were being adopted in other parts of the nation and the world, Louisiana’s industry continued to rely on a more traditional approach, based on natural settling and grow-out on water bottoms planted with cultch materials. There are some 1.68 million acres (680,000 hectares) of public oyster grounds in Louisiana, and another 400,000 acres (162,000 hectares) in private oyster leases. Historically, private leases have accounted for roughly 80 percent of the state’s harvests. Common cultch materials include oyster shell, clam shell, limestone and concrete, and the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (LDWF) estimates that it has placed some 1.5 million cubic yards (1.15 million cubic metres) of cultch in the state’s waters over the past century. That number, however, is dwarfed by the amount of cultch deposited by private oyster harvesters during the same period.

Once cultch is deposited, key factors include suitable temperature and salinity, as well as an adequate source of oyster larvae. For many decades, Louisiana’s industry relied on larvae generated on the state’s public oyster reefs, but supplies from several hatcheries have also been utilised in recent years. Remote setting, where larvae are shipped from a hatchery and held in tanks with cultch for several days prior to planting on leased water bottoms, has also become a common practice.

Alternative oyster culture

In Louisiana, the term “alternative oyster culture” (AOC) has recently been coined for growing oysters using various means other than seeding them directly on reefs or other water bottoms. Prompted by a research collaboration between Louisiana State University and Auburn University in 2010, statutes enabling AOC in Louisiana were passed in 2011 to provide for on- or off-bottom cages, racks or bags, as well as suspended string or long-line culture.

Off-bottom culture works best when oysters can be raised individually, instead of in clumps. The key to obtaining single-seed oysters involves hatchery-produced larvae and the use of microcultch, finely ground cultch material with a particle size that will only support a single, newly settled oyster. Several public and private hatcheries currently supply single-seed oysters in the northern Gulf of Mexico, including the Louisiana Sea Grant (LSG) Oyster Research Lab. Since these larvae are produced in a hatchery setting, the option for raising triploid oysters can help offset some of the inherent equipment and labour costs.

Triple-N-Oysters is one hatchery currently supplying the nascent AOC industry, despite being approximately 100 miles (160 km) from the coast. Operated by Dr Steve Pollock, with help from his wife, this indoor hatchery in the state capital of Baton Rouge relies on recirculating technology and intensive hands-on management. With both tetraploid and diploid breeding stock on hand, triploid larvae are regularly produced in this landlocked setting and then transported to a nursery on the coast. Although the facility itself is small, output is not. One recent spawn resulted in 15 million larvae ready for setting.

State funding incentives

In May of this year, LSG announced a programme to encourage development of AOC in Louisiana waters over the next few years. Funding will be based on a $3 million grant from LDWF, and the Iberia Industrial Development Foundation will disburse $1.8 million of the funds as grants to selected AOC operators. Eligible applicants will fall into one of several categories: parks (designated management units with multiple farms in one location), hatcheries, nurseries or grow-out operations. Each of the four categories will have unique requirements and criteria to consider during the selection process. A numerical scoring system has been developed to aid in the decision process for awards to nursery and grow-out operations, but hatcheries and parks will require more in-depth evaluation during the selection process.

Grant recipients will have to develop their businesses according to an established timeline, periodically report on how the grant contract is being fulfilled in a timely fashion and demonstrate that a marketable oyster product is being grown and cultivated.

As Dr Earl Melancon, a LSG scholar and Professor Emeritus at Nicholls State University with 45 years of experience working with Louisiana’s oyster industry, stated: “AOC isn’t a replacement for the traditional oyster fishery. It’s a supplement for those fishers who have an interest in developing a new method of bringing a valuable Louisiana product to market.”

© John Supan

While the state’s efforts to promote AOC are encouraging, if a potential grower wants to obtain an AOC permit from LDWF they face a gauntlet of regulatory hurdles, not the least of which involves a lack of areas deemed “suitable” for AOC. Basic requirements include:

- A traditional State of Louisiana oyster lease on a public water bottom or an agreement with a private coastal landowner for a private water bottom.

- A Louisiana commercial fisherman’s licence.

- A current Louisiana oyster harvester licence. However, before even applying for an AOC permit, a coastal use permit must be obtained from the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources, along with Federal “obstruction to navigation” and Clean Water Act section 404 permits from the Army Corps of Engineers, a Water Quality Certification from the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, and any other required permits or authorisation from any government agency.

For those committed pioneers producing off-bottom oysters in Louisiana and elsewhere in the northern Gulf, including those that receive supporting grants through this innovative new programme, long-term success will be determined by the impacts of severe weather events, proposed freshwater diversion projects and marketplace preferences.