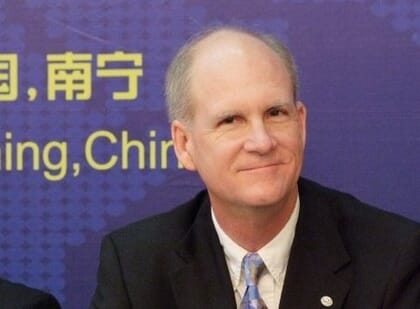

Professor Kevin Fitzsimmons of the University of Arizona’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, believes that Myanmar has huge unfulfilled potential to grow its aquaculture industry.

Speaking to The Fish Site, following the classification of the country’s trap and hold giant tiger prawns as Good Alternative by Seafood Watch he said: “Myanmar has the potential to produce as much shrimp as Vietnam or Thailand. And with less coastal development, lower population and less heavy industry, there are fewer concerns over pollution.”

And he hopes that the current regime will help to promote this development.

“During the military dictatorship, Myanmar’s industry and education system regressed. There is a great need for capacity building from basic education, to vocational training, as well as technical updates for farming practices. The new government is working with several international donors and NGOs who are focused on assisting the industry to develop in a sustainable manner that will benefit farmers and both domestic and international consumers.”

Prof Fitzsimmons was speaking to The Fish Site after Seafood Watch, which has some of the most stringent environmental standards in the sector, determined that extensively farmed giant tiger prawns (Peneus monodon) reared in ponds in Myanmar under the Southeast Asian Shrimp Aquaculture Improvement Protocol’s (SEASAIP) Level 1 Standard qualify as a “good alternative” choice.

The EU-funded Myanmar Sustainable Aquaculture Program (MYSAP) worked closely with the Asian Seafood Improvement Collaborative to develop the information and data that the Seafood Watch Evaluation team needed to determine that giant tiger prawns raised in trap and hold traditional ponds qualify and Professor Fitzsimmons, who is currently based in Myanmar, played an important role in helping the country’s monodon farmers to engage with the certifier.

© University of Arizona

“I’ve worked alongside U Soe Tun on both the SAESIP committee as well as the EU MYSAP project and we’ve hosted visits from the SAESIP-ASIC team to Myanmar to personally visit many of the farms and meet with over 200 of the trap and hold farmers,” he says.

“Although the Myanmar farms and product have not technically received a certification per se, the classification is important for producers as it is indicative for buyers that Seafood Watch has reviewed and evaluated the farm practices and environmental impacts and found them to be acceptable and grade out in their Best Alternative category. For the farmers this means that many more markets are open to them and that they might be able to get a better price for their product,” he adds.

The Seafood Watch approval also shows how traditional farming methods shouldn’t be overlooked by aquaculture developers.

“The trap and hold system is one in which the farmer builds a dike around a section of mangrove estuary,” explains Prof Fitzsimmons. “At high tide, the water gate is opened and water carrying larval shrimp flows in to fill the pond. Closing the gate then traps the water and juvenile shrimp. Over the next few months they grow naturally depending on the productivity of the estuary, grazing on all manner of detritus, algae and smaller invertebrates. On subsequent high tides additional water might be added to replace evaporation or seepage. Several months later at a low tide, the gates will be opened the shrimp caught in nets as the water flows out.”

“The system is deemed so sustainable as no additional feed, fertiliser, chemicals or antibiotics are introduced to the ponds; there is no effluent pollution from the ponds; and no exotic species are used,” he adds.

According to Prof Fitzsimmons, in the 1980s and 1990s almost 60,000 acres of mangroves were farmed this way in Myanmar, with production reaching 30,000-40,000 tonnes. However, due to embargos, cyclones and low shrimp prices, the area farmed and production level is now only 20-30 percent of this total.

Closing the cycle

One of the remaining sustainability issues of the system that needs to be tackled is the use of wild-caught rather than farmed shrimp larvae, but Prof Fitzsimmons is currently involved in a project which aims to change this situation by closing the monodon production cycle.

“The MYSAP project is renovating a government hatchery to produce more high quality domesticated monodon broodstock which will be provided to private sector hatcheries. These private hatcheries will be able to sell post-larvae (PL) to the trap and hold farmers who report that numbers and quality of wild PL’s has decreased in recent years,” he explains.