The current challenge of food security posed to developing nations is extremely serious. Last year alone a further 40 million people were pushed into hunger worldwide, bringing the overall total of undernourished people to 963 million. The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) says that this growing trend is primarily due to higher food prices and it warns that the current economic slump will only make the situation more desperate as countries seek to secure national trade and development.

Developing countries cannot rely on aid to see it through these troubled times. To meet this challenge requires improvements in food security, income and employment on behalf of the countries at risk. The role that aquaculture can have to achieve these three goals is clearly evident.

The Value of Fish

Aquaculture has proved itself to be an economically successful industry ever since it was first introduced and there are no signs that is will be weakening any time soon. Demand for fish increases year-on-year, but at the same time capture fisheries have been unable to boost their total harvests since the late 1980's. Declining wild fish stocks has limited the annual catch to 90 million tonnes. In response aquaculture has risen to fill this gap.

Aquaculture is now the fastest growing food production system globally, with an increase in production of animal crops of about 9.3 per cent. According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), aquaculture will continue to grow at significant rates through 2025, remaining the most rapidly increasing food production system in the world.

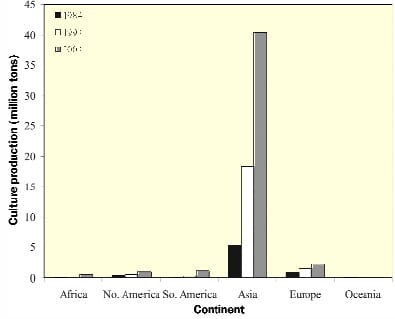

Culture production, in millions of metric tons, in 1984, 1994, and 2004 for each continent.

Source: FAO (2005).

The International Food Policy Research Institute forecasts that the annual increase in seafood consumption will be about 1.5 kilogrammes (kg) per person in 2020. Meanwhile the global population is expecting to increase dramatically, which would make the overall demand for seafood products considerably higher than it is now.

Not only is aquaculture an increasingly lucrative trade, it is also highly favourable to many developing countries. The developing world currently has a huge dominance over fish production. 72.4 per cent of all capture harvest (by mass, including only animals) and 92.3 per cent of all culture harvest occurs in developing countries.

According to information derived from the FAO, in the year 2002 "seafood exports valued at US$56 billion generated more money for developing countries (US$28.1 billion) than did exports of coffee (US$5.1 billion), tea (US$2.4 billion), bananas (US$2.9 billion), rice (US$4.5 billion), and meat (US$12.9 billion) combined".

By 2004, the value of total seafood exports had grown to US$71.5 billion; "at least 43 per cent of those exports, by weight, came from aquaculture". Despite the high export value of fish crops, about 75 per cent of all seafood harvested by developing countries was consumed locally rather than exported.

Although it can be argued that this equates to a large loss in profit, the benefits to local health cannot be undervalued. The nutritional value of fish can help fight malnutrition in developing countries. The high content of protein, fatty acids, water soluble vitamins and minerals are all essential for human survival.

As the global population boom is largely focussed in the developing world, a plentiful supply of fish products might be essential to stave off even greater levels of hunger and malnutrition than we see today.

The Creation of An Industry

According to the recent report, Aquaculture Production and Biodiversity Conservation, produced by James S. Diana, world growth in freshwater aquaculture will most likely take place in both semi-intensive systems, which will produce food for local consumption, and intensive systems, which will be designed to accommodate local and export sales.

* "Nutrients not removed by harvest of fish are largely immobilised in pond sediments, and so impact on the environment is near-neutral" |

|

Peter Edwards, author of Aquaculture, Poverty Impacts and Livelihoods

|

Although the intensive aquaculture operations used in developed nations are both expensive and complicated - requiring skilled staff and large investment - semi-intensive systems in developing countries are well adhered to local life, where natives often grow up in a similar fishing environment. Similarly, input costs and labour are also cheap by comparison to their foreign counterparts.

Peter Edwards, in the Natural Resource Perspective report: Aquaculture, Poverty Impacts and Livelihoods, explains how semi intensive aquaculture operations can be developed by modifying a rice field or extensive pond system. Mr Edwards goes on to report that nutritional inputs can be on-farm by-products such as manure and crop residues, whilst intensification can be through relatively cheap inorganic fertilisers.

Because of the low input costs associated with this produce, it can can be marketed at relatively low cost and be affordable by poor consumers, rather than merely as a delicacy.

"Nutrients not removed by harvest of fish are largely immobilised in pond sediments, and so impact on the environment is near-neutral", adds Mr Edwards. The environmentally friendly aspects of these semi intensive practises may also come to raise the value of the product on an increasing consumer conscious foreign market, where the effects of intensive aquaculture operations are currently receiving lot of negative media attention.

The Natural Resource Perspective also examines how small-scale farmers can benefit from the construction of ponds where land is frequently degraded. The pond can become a focal point of water supply within the region, allowing for more fertile land and agricultural diversification. Those natives who are landless can benefit from the introduction of aquaculture on common water bodies. However, Mr Edwards warns that those without land or access to water have no way to turn to aquaculture.

Conclusion

Aquaculture has contributed to the economy of developing countries for many years. China, Indonesia and Viet Nam have all benefited hugely from fish farming. Now, many more developing nations are turning their attention towards it, with large government schemes and heavy investment.

For them to succeed, farmers and consumers must understand the real market value of their products and investment in appropriate technology must be better understood. Mr Edwards says that a supply of seed is crucial and is often a major constraining factor for adoption of aquaculture and good institutional support is usually required for new entrant farmers in the form of extension advice or inputs.

Although an increasing number of developing countries are turning to aquaculture, its beneficial attributes are often ignored. It is important that its potential benefits are raised with agricultural and rural development professionals and policy makers as well as with the local farmers. The opportunity is there to be taken, simply realising this is the greatest obstacle to it.

January 2009