Early days

I first arrived in Zambia from England in 1979 to participate in the management and running of the largest cattle operation in the country, having qualified with an honours degree in animal production from Wye College, London (latterly linked to Imperial College). The reason for first coming to Zambia was a chance letter from a friend at the main Zambian Agricultural College at that time. I had just completed a year's contract in the dairy farming industry in Canada and was looking for new opportunities. That was 41 years ago, and I am still here – how one letter can change the direction of one’s life!

Another chance communication which again changed my life came two years later through a fisheries consultant. The managing director of an international industrial business was looking to diversify into agriculture and to recruit a suitable candidate to start up a profitable fish farm in Zambia from scratch. Despite two subsequent changes in the ownership of Kafue Fisheries over the intervening years, I was privileged to remain an employee of the company from 1981 until 2012. I am very grateful to the successive owners, T and N PLC, Komex International, and the current owner for allowing me the privilege to continue on such an exciting journey, and for all the support and encouragement given throughout.

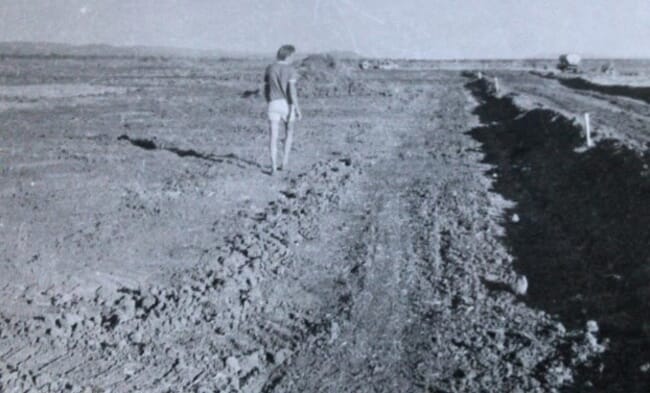

It is worth remembering that in 1981 aquaculture in Africa was in its infancy and it presented a daunting and exciting journey. Initial site selection, I knew from my training, was critical and often overlooked. A great deal of work and time went first into finding the right place and satisfying the main criteria: 12 months’ supply of quality water, suitable soils for a pond-based operation, close proximity to electricity, a local community to recruit staff from, and - perhaps most importantly – being close to a major market, which in this case was the growing capital, Lusaka, 35 miles from the site we chose at Kafue. Having found suitable land which would also allow expansion, my wife and I literally walked in front of a D8 Caterpillar machine to create the initial access and begin to landscape the site.

We called the new company Kafue Fisheries Limited (KFL) and at that time I had zero experience in fish farming. We set about designing a 5-hectare fish farm pilot scheme which included ponds of various sizes and a hatchery fed through pumping (diesel powered) water from the adjacent Kafue River. The Kafue is the longest river lying wholly within Zambia, at over 1600km in length, with more than 50 percent of Zambia’s population living within its river basin, of which over 65 percent of these are classed as urban. Its water was increasingly being used for irrigation and industrial applications, with hydroelectric power also generated downstream at the Kafue Gorge power station.

Back in the early 1980s our water supply was both reliable and generally of the quality required for a commercial fish farm. In those days it had far fewer pressures from population increase and urbanisation. But as Zambia’s population rose from 5.6 million in the early 80s to over 14 million when we left the farm in 2012, circumstances had very much changed. Pressure from local industrialisation, housing construction and intensifying agriculture, coupled with changing weather patterns due to climate change, meant that the Kafue River was becoming a different water source, perennial, but subject to unpredictable, more seasonal water fluctuations, and increasingly vulnerable to localised pollution and overexploitation.

Building the farm and the business

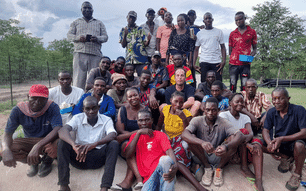

Going back to the early 80s… once the ponds were built and the water supply secured, it was then a question of looking for good staff. Initially all of the staff were recruited from the local community, within a 10-15km radius, and in the main this recruitment has continued over the decades. The basic principles of the integrated production system we developed can be both simple and complex. The key was to develop systems which were site-specific, then to carefully develop a staff team who felt included, valued, and proud of their work. Also, through patient and hands-on training, individual staff members not only understood their own jobs, but also had to work together as a team. Fish farming like all agricultural food production is not and cannot be a 9am-5pm job. Many of the staff members who first came to the farm with only a basic primary or secondary school education, have gone on to excel elsewhere in other Zambian hatcheries, grow-out farms, pig breeding or other agriculture-related employment. Many employees remained on the farm for decades, a major contributing factor to the stability of the business – one senior staff member recently retired after 38 years continuous service.

Next, it was all about securing good quality fingerlings for stocking. In the early 80s there were no commercial hatcheries in Zambia, and little or no knowledge of suitable species or suitable production systems. At that time the only option for starting up aquaculture was the time-consuming process of finding and translocating fingerlings from both natural and artificial waterways, then trialling these within different production systems. We and our staff learnt together daily as we went along.

Integrated production systems which had been developed over the centuries in the Far East fascinated me, as they seemed to make biological as well as economic sense. It was a new concept to us then and guided the direction in which the farm developed, as we set up initial trials to provide (we hoped) proof of concept. Utilising a waste product from livestock, eg organic pig manure, in order to create a “biological soup” in fishponds to produce a higher value protein source within 8-10 months in the form of farmed fish, seemed to have interesting and exciting possibilities. The Chinese, after all, had been doing it for centuries. Other trials based around the same principle were carried out in parallel: purchased inorganic fertiliser (N:P:K compound fertilisers from local fertiliser factory), dried organic fertiliser (in the form of bought-in commercial chicken manure) as well as simple but functional housing for live pigs on the pond banks, with the fresh manure being washed into the ponds twice daily. With regular sampling to monitor growth and survival rates, it was clear that the on-site fresh pig manure created a green soup full of life in which the fish thrived. There were no disease problems with the fish and all trial species thriving.

One of the strengths of such integrated systems are they have more than one income source, ie pigs and fish. We carried out many trials to determine the optimum ratios for pig biomass against fish stocking densities per unit area of ponds under site conditions, something that was not always linear or in fact simple. As the farm intensified, we looked to find and then reach the carrying capacity and production potential for the site through increased pig and fish numbers per hectare. This involved the introduction of aeration, and importantly the development of a complementary, supplementary, low-cost, 17 percent crude protein floating pellet which further improved growth and productivity.

By trial and error, we did achieve “perfect cycles”, whereby a batch of 40 pig weaners were stocked simultaneously with a 1-hectare fishpond containing 30-35,000 fingerlings of 2-3 g average. With the various expansion phases, we never exceeded 1.3 hectare individual pond areas and 1.3 metre depths. This gave us a manageable size of pond, allowing controlled harvesting and the marketing of an entire pond as fresh fish. As both fish and pigs increased in biomass, so manure loads increased. By the end of the 5–6-month cycle at 26-28°C water temperatures, both fish and pigs went to market and the pond was then rested (drained and dried).

On the pig production side, we went through years of breeding quality pedigree strains (imported from Europe), including the “Berkshire”, an old-fashioned breed with potential for the small-scale farmer.

The markets and consumers

At times changing markets price and demand meant holding back, with the pig/fish stocking ratios not in sync, and excess manure being redistributed to other ponds in need of extra fertilisation. Pork production done well was very much economically successful in its own right, and the farm developed a lucrative market with at first one, then many, butchers and processors, with the production and sale of the first Hungarian sausages in Zambia. These sausages are to this day by far the most popular processed meat product in the country. The first pork butcher with whom we did business for 17 years expanded over that time from one outlet in central Lusaka to various outlets, a multi-species abattoir and meat processing factory. The two complimentary businesses grew together, producing new product lines and developed a well-known brand which impacted positively on local and Lusaka markets.

A similar, step-by-step process occurred developing our fish marketing, where initially a trustworthy inner Lusaka food shop owner grew his business alongside ours over a period of 31 years. In the early 1980s farmed fish for sale were almost unheard of anywhere in the country. Zambia was blessed with wild fisheries catch from its numerous, at that time productive and sustainable, rivers, lakes, and wetlands which satisfied demand. Whilst prolific, this supply was seasonal and often poor quality and “spoiled” by the time fish reached urban markets. Our advantage was that our very fresh product was available throughout the year, in some cases still alive in water, the latter being a big crowd-puller. The food shop owner, a wonderful man who understood the importance of a fair price to the farmer, and at the same time accepting a small margin, thus passing on a final, quality product to the growing numbers of urban customer at affordable prices. This two-business combination allowed both to grow exponentially over the next three decades. Africa's rural economies are still often dominated by exploitative middlemen/women in which the producer and customer are ultimately the losers. We were very fortunate indeed with the two market chain partners we had.

This busy food retail shop (pre-supermarkets arriving) was located within Lusaka’s new urban housing estates and sold basic commodities such as dry beans, rice, dried kapenta, as well as unpacked fish in open chillers and a range of fresh vegetables. Individual customers were able to select their own fresh farmed fish, which was much appreciated, whilst bulk sales took place to other mostly female retailers/marketeers who were then able to sell their fish on to lower income customers. We also developed a market for our second-generation smaller fish (2g up to 80g) which in the early days we regularly removed from our mixed sex growout ponds. These were bought again by mainly small-scale local female retailers who sold readily to low-income households all over Lusaka, who benefited from access to fairly-priced, small, fresh fish.

Zambians have always been prepared to pay premium prices for larger fish. As the farm developed over the years, superior genetics, all-male populations and supplementary feed lifted the "large grade" from 200+ g to 500-600 g, with an extra-large grade added to include fish between 700-800 g. Pricing structures developed over the years, related to our experiences and market demand. It is worth remembering that our grades sales structure was set up and applicable to the one outlet that absorbed the farm’s total production.

The question is often asked regarding consumer resistance to farmed fish produced from an integrated system using pig manure. In our case this was never an issue affecting sales for two reasons. Firstly, as mentioned above, the advantage of fresh-tasting fish with a healthy appearance was huge. Secondly, we explained from the outset to both our staff and more importantly customers, the role of manure in growing the fish. The concept of animal manure acting as a fertiliser, for the production of natural micro-organisms on which the fish depended on for their healthy nutrition was understood. Perhaps this understanding was assisted further by the trials we had conducted using artificial fertiliser to give the same end-result. Also, with our customers we related the analogy of natural wetlands grazing systems that exist throughout Africa on river flood plains which all Zambians know so well. In this case the thousands of Kafue lechwe and zebra that graze on the river floodplain with the deposited, productive, animal manure then benefiting wild fish nurseries and production with a “natural green soup” of their own.

Species, broodstock and hatchery

During the development of the farm we experimented with many species in the early trials O. andersonii, O. macrochir, T. rendalli, followed by the introduction of O. niloticus and O. aureus. We also worked with Clarias gariepinus, using them as controllers of second-generation tilapias in the growout ponds. We also grew the major carps – grass, common, silver and bighead. Although relatively simple to propagate and grow, the consumer did not take to any and they were phased out. "The customer has spoken" and no more so than in Zambia which is a great fish eating nation and where tilapias rule.

Unfortunately, population growth pressures including overfishing are leading to the near extinction of many indigenous cichlid species, several with varied gene pools and commercial potential, and which would be a tragedy to lose for future generations.

A good example of the O. andersonii tilapia species in the early 1980s

Oreochromis andersonii showed the most commercial promise in terms of performance and growth rates. As with all tilapias in aquaculture, the challenge was the control of second-generation progeny competing with those originally stocked. At that time the concept of sex-reversed all-male tilapia fingerlings was very new and one of the early pioneers, researcher and small-scale fish farmer Dr Rafael Guerrero resided in the Philippines. My wife and I travelled to meet him and other leading forces within the industry in 1987, including the influential World Fish Centre, a trip well worth it from all we learnt in such a short time. Sex-reversal is now the accepted norm globally across 95 percent of commercial tilapia production and has been for many years. But at that time, it was radical and changed the industry for decades to come, much as artificial insemination (AI) has become now integral to the livestock sector.

We produced O. andersonii, a fine fish, for many years on a commercial scale.

Inevitably the more aggressive O. niloticus hybridised and pure lines were lost in the fullness of time. As a species andersonii had attractive traits relevant for us when compared to niloticus: more cold tolerant, easier to handle due to their "softer" dorsal spine, and its stronger silver colour making a big difference in marketing sales in contrast to its competitors. Visual appeal was, and still is, very important for an increasingly discerning younger and middle-class urban audience, and certainly still adds to comparative market value.

Design and development of the hatchery was very much an evolving process, in some ways reflecting development internationally of tilapia production. In the early stages fingerlings were stocked in earthen ponds with selected broodstock and the resultant progeny of mixed-sex fry produced and removed and size graded on sorting tables. By 1987 the process was intensified, and 17-methyl testosterone (17MT) was used to produce all male tilapia. In the late 1980s, in addition, we trialled the Swansea University Y-Y technology, but preferred the hormonal sex reversal for both its simplicity and flexibility. By the 1990s, earthen ponds gave way to small concrete hatchery tanks for broodfish, collecting the small swim-up fry daily from the tank edges. These were then transferred to small raceways and subjected to the 17-MT treatment. Finally, we went on to manual collection of fertilised eggs and developing embryos carefully from brooding females and putting these straight into incubators and then bowls/trays. The sex reversal treatment was then given post-yolk sac absorption and precisely at swim-up stage, which significantly improved the all-male percentages of our fry.

The 80s saw huge strides in the dispersal and improvement of tilapias as a standard aquaculture species across the globe, with the focus being channelled towards Oreochromis niloticus, to a point today where it represents the major farmed species on earth after the carps. However, with a few notable exceptions across our continent such as Egypt, Zimbabwe and Ghana, and some more recent major commercial investments in Zambia and Kenya, tilapia production on a small and medium scale still lags far behind its potential. It is hoped that far more interest and resources are given to protect and develop other tilapia species, such as O. andersonii and similarly far more resources channelled to develop specific “proven to be financially viable” systems which positively contribute to fish production as an important protein source as well as income enhancement for the smaller operators. The challenge is not easy, but a starting point which has been largely neglected despite being so obvious is to appreciate that Africa is a unique continent requiring unique solutions.

Perhaps too much time and capital have been invested in trying to transfer to-the -letter aquaculture systems which do not fit the African model. I would suggest that one of the main reasons for the long-term (31 year) commercial success of our farm was that, although concepts and ideas were taken from other parts of the world, their implementation always had as the starting point the question "What will work and is financially viable in this environment?” taking into account local physical conditions, employment of local staff, and emphasising end products must be acceptable to fit local markets. Kafue Fish Farm (KFL) is still operating 31 years on, has expanded to over 120 hectares of pond area, and has for decades been recognised as the largest land-based fish farm on the continent. Since reaching commercial viability in 1986 KFL has also been one of the longest running commercially viable farms on the continent.

Along our journey we were very blessed to have the support of some special people: my dear friend Steven Roberts the fish shop owner, and Professor Alex Woynarovich (sadly no longer with us) and his son who selflessly passed on their vast knowledge on farming fish and setting up and running commercial fish hatcheries. On the pig side my mentor was Robert Overend, also sadly no longer with us, He had his own AI station and two commercial piggeries in Northern Ireland. There were, of course, others including some extraordinary Zambians who were a privilege and blessing to work with. In the up-and- coming younger generation there are many more, with whom in future I hope I can pass on from “my journey” and experience whatever is relevant for them to catalyse further fish farms which have real meaning.

Finishing my full-time commercial livestock career in early 2021, I now hope to make further contributions towards development of entrepreneurial, small and medium-scale farmers’ systems that are affordable, implementable, and financially viable. The rural poor need to improve their nutritional status, as well as to create a broader income base, giving them a more secure and reliable future. I have a strong feeling that the concept of "integration" in food production in the broadest sense may have a significant role to play in the longer term, within the finite resources that will be available to us, maybe much more than current commercial aquacultural thinking suggests.

Fergus can be contacted at email fergusoaflynn@gmail.com