The study, the results of which will be published in the upcoming edition of the journal Aquaculture, compared the growth, development and survivability of growth hormone transgenic Coho salmon with selectively bred Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) in four separate trials across a range of production conditions.

Though these results are a huge boon for advocates of transgenesis, the research team notes that their trials aren’t reflective of commercial aquaculture conditions. They also stress that achieving greater growth rates and slaughter weights shouldn’t be the sole consideration for producers. Other research indicates that transgenic growth hormone fish can exhibit lower reproductive success and altered swimming ability when compared to their wild-type counterparts. Because of this, the team suggests conducting trials with transgenic fish on a commercial scale to get a better sense of their performance in a production environment.

Background

As sustainable salmon aquaculture scales up production to meet demand, fish farmers are exploring new ways to optimise fish growth. Capitalising on salmon growth would make the industry more resilient and profitable – shortened production times and improved feed conversion ratios would allow producers to raise more fish and better predict their yields each year. Currently, the industry uses two different strategies to enhance growth: selective breeding and transgenesis.

Selective breeding programmes develop strains of fish with strong growth performance over multiple generations. As the breeding programmes have progressed, they have developed domesticated strains of Coho salmon that grow faster and larger than their wild-type counterparts.

To create transgenic salmon, researchers modify wild-type fish so they contain a gene for heightened growth hormone expression. Previous research has shown that transgenesis can induce a 37-fold growth in young salmonids. Though transgenic Coho salmon haven’t been commercialised yet, producers and researchers are quickly approaching that milestone.

Despite transgenesis and selective breeding following similar biological pathways, researchers have not directly compared the growth rates of selectively bred domesticated salmon and growth hormone transgenic salmon. There’s also a gap when it comes to their performance in different environmental and production conditions.

The trials

The research team, based at the Pacific Science Enterprise Centre (PSEC, West Vancouver, BC), wanted to compare the growth and survival of domesticated and growth-hormone enhanced transgenic salmon at different developmental stages and in different experimental and rearing conditions. To test this, they designed four separate trials.

Experiment 1

Researchers compared the growth of selectively bred domesticated (D), transgenic (T) and hybrid domesticated/transgenic salmon in standard freshwater hatchery conditions over 10 months. The team tracked 30 fish per cohort and measured any differences in growth. They recorded and removed any mortalities to calculate the average survival rate.

Experiment 2

The team measured the maximum potential growth in D and T Coho salmon by comparing weight-matched fish in the groups as well as the 30 heaviest fish in a standard freshwater hatchery environment over six months. Before the trial period, the team raised 300 D and 300 T salmon in water temperatures optimised for maximum growth. After the habituation period, the researchers took 90 fish from each strain and measured and weighed them. They were then weight-matched and tagged before being put back in the tanks. The trial continued for an additional seven months, with the fist being sampled twice again for weight and growth measurements.

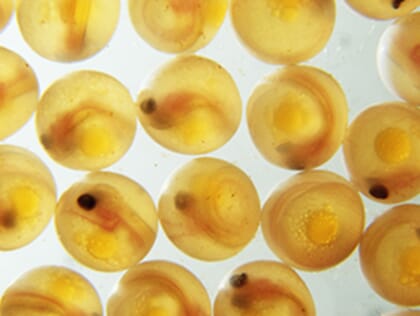

© NOAA

Experiment 3

This trial wanted to observe the effects of social interaction and inter-strain competition on growth in a standard hatchery environment. The researchers measured this by comparing the growth of domesticated and transgenic salmon when reared both together and separately.

T and D salmon were raised until smolt in two separate tanks. From there, they were size-matched, tagged and split into three treatment groups. Group one contained 50 transgenic salmon, group two contained 25 transgenic salmon and 25 domesticated salmon and group three had 50 domesticated salmon. Mortalities were recorded and removed to calculate the mean survival rate.

Experiment 4

The researchers investigated the lifetime potential growth in D and T fish when they were reared together in large, land-based tanks after smoltification. This trial hoped to identify the life stage where the growth advantage of transgenesis or domestication became more pronounced. The researchers reared D and T strains together in low density seawater tanks after the fish had smolted. After this point, the fish were tagged and randomly distributed to experimental and control tanks. Their growth was tracked for the rest of the trial period.

Key results and conclusions

In all four trials, the transgenic salmon grew both faster and larger than the selectively bred salmon. However, there were some nuances in the recorded results.

Experiment 1

In this trial, the hybrid group had higher average finishing weights than fish in the T group. Salmon in the D group did not show the same level of growth. This suggests that the growth enhancement from both domestication and transgenesis can interact to produce larger fish.

Experiment 2

The average weights and lengths of the weight-matched T salmon were significantly larger than the weight-matched domesticated fish. The 30 heaviest transgenic fish were larger than the 30 heaviest domesticated ones. However, this difference wasn’t as pronounced as the one seen in the weight-matched groups. The researchers felt that this indicates a potential for further growth selection in selectively bred salmon.

Experiment 3

The researchers noted that after size-matching, T salmon grew at least two-fold faster than D salmon. Average body weight and length in transgenic salmon was larger than the domesticated salmon. The trend was observed if the cohorts were mixed or kept in strain-only groups.

Experiment 4

Before smolitification and tagging, the fish in the experimental groups differed in weight. At the end of the trial, the average weights of the transgenic salmon were significantly larger than the selectively bred salmon. Though the researchers observed fluctuations in growth rates between the groups (with Coho salmon in the D group showing higher growth rates during some sampling periods) transgenic fish had a weight advantage when they reached maturity. Transgenic fish also had a higher average dress weight at the end of the trial.

Based on these results, the researchers concluded that there is a noted growth advantage to using transgenic fish relative to domesticated fish. They suggest that growth hormone transgenesis could complement selective breeding programmes – allowing the aquaculture industry to quickly produce fast-growing Coho salmon.

Though these results are promising, the team was quick to note that their trials were relatively small-scale. Scaling these trials up to mimic commercial conditions may provide greater clarity on the benefits of using transgenesis to promote growth.

The full study, "Comparison of growth rates between growth hormone transgenic and selectively-bred domesticated strains of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) assessed under different culture conditions," is now available as an open access piece in Aquaculture. It was funded by Fisheries and Oceans Canada.