The former commercial fisherman shares his thoughts on the future of the aquaculture industry and his bid to ‘legalise the other weed’ with The Fish Site.

How does your operation work?

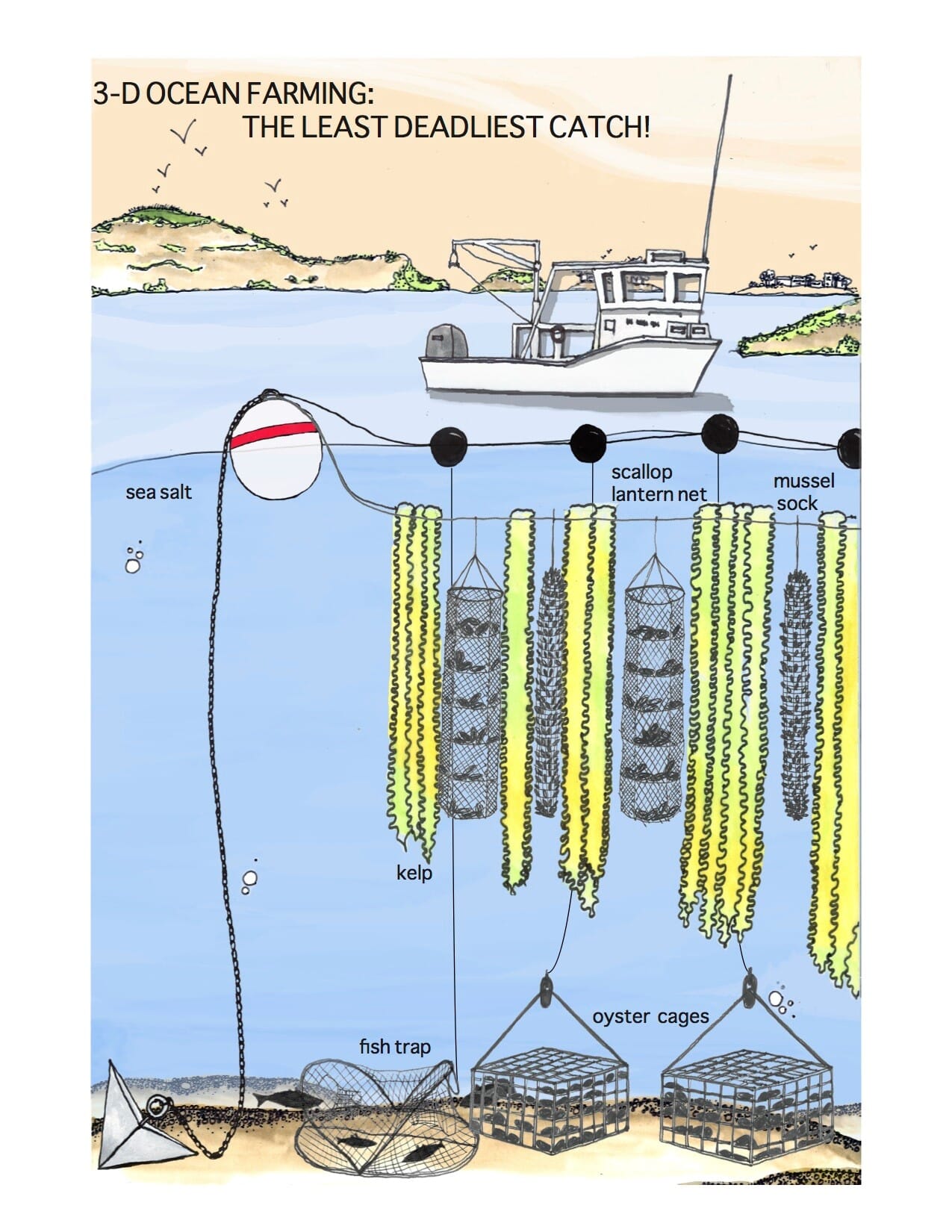

Our farms typically feature seaweed, mussels and scallops, which grow down from floating ropes. Below these oysters and clams are grown in suspended cages and their growth rates are improved by the nutrients produced by the species above them in the water column.

There are two parts to the business. Greenwave, the non-profit element, helps to train potential farmers for up to 2 years before they adopt our growing systems. Due to the fact that it’s not currently permitted to grow seaweed in a number of coastal states we are also about to launch a campaign, under the slogan ‘Legalise the Other Weed’.

Then there’s the for-profit Sea Greens Farms, which buys all the produce grown by our farmers and sells it through a co-operative, based in Fair Haven Connecticut, to buyers – mainly restaurants – from across the US. We also provide Greenwave farmers with seaweed seed at cost price, as well as spat from our dedicated shellfish hatchery.

What sort of people have adopted your farming model?

I set up the system with former fishermen in mind, but there’s a wide range of people – from fifth generation fishermen and third generation lobstermen, to traditional farmers who can’t afford to buy the land they need to farm terrestrially.

How widely has it been adopted?

There are currently 10 farms that use the Greenwave system, scattered down the coast between Maine and New York City. All we need are gravity and a pile of rope, which is why the farms are so cheap to set up – around $20,000 apiece. Despite this they can be very productive, the growth rates of the kelp varies from 5-16lb per foot, and the farmers are producing roughly 10-20,000lb of kelp and 250,000 shellfish per acre.

We’ve had requests to help set up the Greenwave system from potential producers in every coastal state in the US, as well as from 20 countries around the world, but we’ve decided to pull back from global expansion requests as we really want to fine-tune the system here before we start replicating the model. We are, however, now starting our first farm in California and are exploring how to work internationally, we’re currently discussing the idea with fishermen in the Lake District, in England, which is one of the leading contenders [for our international expansion] at the moment.

What’s your background?

I was born and raised in Newfoundland and, after dropping out of school, worked as a commercial fisherman in the Bering Sea, on the Grand Banks and out of Gloucester. After the Grand Banks cod crash in the 1990s I worked on salmon farms in Canada, but my experience of the industry made me question its long-term sustainability – at the time there were many problems with pollution and antibiotic use.

I then set up as an independent oyster farmer in Long Island Sound. It was about the time that the boutique oyster sector started to take off and proved quite successful for a while. But after I was hit by Hurricanes Irene and Sandy two years in a row [2011 and 2012] – which wiped out 90% of my gear and most of my profits – I decided to diversify to decrease the risk and lift production off the bottom, to make it less susceptible to storm surges.

I then became one of the first polyculture/IMTA farmers in the US and started to produce scallops, mussels, oysters, clams, sugar kelp and some grassilaria, all vertically integrated on the same site.

What are the main principles behind your project?

The key to our model is to only grow species that you don’t need to feed. It’s not necessary to grow species that people want to eat, if you can work on shifting tastes. I’m now a huge fan of meals that are a kelp/mussel combo, for example. It’s a bit like the trend in meat consumption, in which something that was the main ingredient – be it shellfish or beef – is now more peripheral on the plate.

Kelp is currently the major plant produced by our farmers – I think of it as the soy of the sea, but less evil, and it’s a great ‘gateway drug’ for what we’re doing. However, there are over 10,000 species of oceanic plants out there – if I had a bottomless supply of money I would investigate the properties of all of them.

In order to be successful, however, we need to draw on a huge range of skills, from engineers to chefs – the latter need to help us re-imagine the seafood plate and create climate-friendly cuisine. We’ve already shown that you can sell kelp outside of Asian markets – we’ve de-sushified it and tapped into mainstream US dishes and we’re currently looking to develop kelp noodles and kelp jerky. Demand for our seaweed already outstrips supply.

What are the main challenges you still need to overcome?

One of the main challenges is the range of growth rates we’ve experienced at the farm sites. We need to fine-tune site placement and, ideally, we need to do a year of testing before establishing a site.

Another thing we have to consider is what this network of farms is going to look like in our oceans – should we aim for 1000-acre farms, or a network of smaller producers? I prefer the concept of distributed production and hope we’re not going to repeat the mistakes made by industrial agriculture and aquaculture – we hope it’s not business as usual.

Do you think you might be able to influence conventional, monoculture aquaculture producers?

Conventional aquaculture is still struggling with biological problems and social buy-in. I hope we meet somewhere in the middle once they’ve seen our way of creating a restorative circular community.

How have the local commercial fishermen received the appearance of the farms?

Fishermen surround my farm with gill nets - we’re basically creating an artificial reef and excellent fishing conditions for them. They’re also interested in the possible jobs that the concept could produce. Indeed, 40 fishermen showed up at a meeting we held to discuss the Greenwave idea. They understand the need for diversification, but – like me – it takes some time for people who have essentially made a living from hunting to come to terms with the thought of growing vegetables for a career!