Click on image to enlarge

In my last article, I highlighted the key components that can improve the Indian aquaculture sector’s resilience. Out of the many obstacles that I flagged the need to improve access to low-interest finance is the top priority. While India may be a top aquaculture production hub, which generates 10 million tonnes of aquaculture produce each year, accessing formal credit is the biggest challenge for most farmers, as the industry currently lacks structured financial products like loans and insurance.

Indian aquaculture employs nearly 10 million people, many of whom live in rural and coastal regions. More than 90 percent of Indian aquaculture produce comes from small/medium-sized farmers, but the majority of them lack access to formal credit that is needed as working capital to purchase key farm inputs at critical junctures in the aquaculture cycle. The absence of formal credit forces them to rely on informal lenders – such as local retailers and farm-input distributors – and thus enter high-interest traps.

One of the key themes to emerge from farmers’ interactions with such lenders is that very few are aware that they are paying annual interest of up to 60 percent, which significantly reduces their margins in every crop cycle. Furthermore, farmers receive minimal discounts (~10 percent) when they buy farm inputs on credit from the retailer, while cash purchases can result in up to 30-40 percent reduction in price.

One notable example involves Sundaresan Rangasamy, an aquaculture farmer from Cuddalore, in Tamil Nadu, who bought feed and farm inputs on credit from the local retailer. Post-harvest, the retailer forced him to sell his produce to his preferred buyer at a lesser value than the market price and, having borrowed the credit at 38 percent interest, meant that he barely made a 2 percent operating profit from his five months of toiling at the farm.

Many readers will have heard similar stories from across the country. Farmers are, all too often, trapped by high interest rates, while lenders often dictate what brands of inputs they buy, what time they harvest their fish/shrimp, and where they sell their harvest. These factors can hinder the individual farmer’s earning potential in every culture cycle. When we speak of ambitious targets and transcending the entire sector, the key issue to address is the creation of a system of formal credit that can be accessed more easily by farmers.

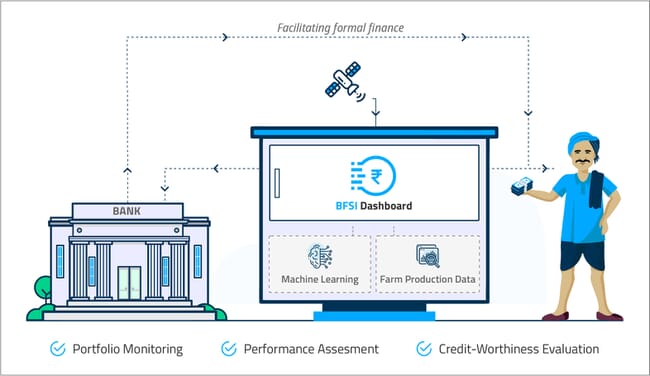

At the moment, formal BFSI institutions are staying away from offering farm credits and insurance products to the aquaculture sector due to the lack of transparency in the value chain. This is primarily due to the low technology adoption by aquaculture producers, which leads to poor transparency and a lack of risk mitigation tools. Lack of credible data makes it impossible for organised banking, financial services and insurance (BFSI) institutions to either assess the creditworthiness of farmers or offer products to the neediest ones. As the entire sector is ramping up towards the next blue revolution, it is now essential to bridge the gap between the farmers and financial institutions.

Click on image to enlarge

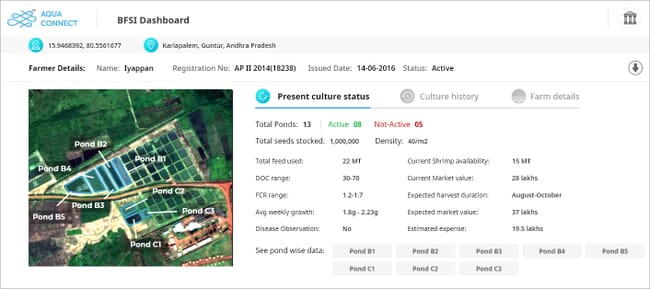

BFSI institutions have largely figured out the risk-mitigation for the Agriculture farm sector, as the crops can be captured through satellite-remote sensing and data analytics technology solutions. However, aquaculture activities pose a different challenge to BFSI institution's risk mitigation strategy. Underwater operational nature of aquaculture activities requires a different approach and technologies that allow banks to easily monitor their portfolio in real-time/near-real-time. It is therefore essential to look towards developing and deploying technology solutions that provide risk mitigation solutions to aid both underwriting and monitoring teams.

These technologies shall allow banks to evaluate farms using data – such as farming patterns, disease records, and production volumes – and also undertake pond-level validation with the help of satellite imagery. Eventually, these solutions will help banks monitor their portfolio assets, track their current performance, evaluate credit, and assess the risks.

Lack of insurance is another big impediment for banks to lend to the aquaculture sector. If technology could help to enable the widespread provision of insurance it would give a compelling reason for banks to enter this sector and extend their product lines.

Such technology solutions shall eventually make farmers bankable, while simultaneously helping banks to achieve their public sector lending targets (PSL) with lower non-performing assets (NPAs). On the production front, this would unleash the aquaculture sector’s growth by allowing for the utilization of neglected land resources, inducing entrepreneurship among rural people, especially women, and providing livelihood opportunities for the greater good of society.

One possible model that could be replicated can be the Government of India's Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY), a programme that aims to provide a comprehensive insurance cover to farmers suffering crop loss/damage arising out of unforeseen events; stabilising the income of farmers and allowing them to adopt innovative and modern agricultural practices. Such a scheme acted as an incentive for banks to fund regular agriculture and thereby achieve their PSL target and a similar model could be applied to aquaculture.

Aquaconnect is part of Hatch's portfolio, but The Fish Site retains editorial independence.