Employment

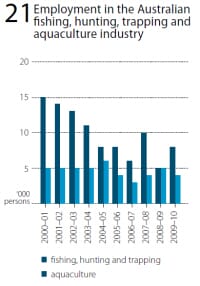

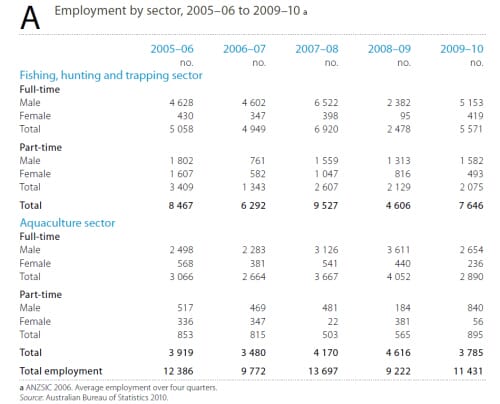

Fast facts- In 2009–10, 11,431 people were employed in the commercial fishing, hunting and trapping industry, with 7646 employed in the fishing, hunting and trapping sector, and 3785 in aquaculture enterprises.

- Of this total, 8461 people (74 per cent) worked full-time and 2970 (26 per cent) part-time.

- By gender, 10,228 males (89 per cent) and 1203 females (11 per cent) were employed in the commercial fishing, hunting and trapping industry in 2009–10.

- Compared with 2008–09, total employment in the commercial fishing, hunting and trapping industry increased by 24 per cent (2208 people) following a 30 per cent (1931 people) increase in full-time employment and a 10 per cent (277 people) increase in people engaged in part-time employment in 2009–10.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) does not provide separate employment statistics for the fishing sector, but includes it in the hunting and trapping sector. However, separate statistics are available for the aquaculture sector.

The Labour Force Survey (ABS 2010) shows that in 2009–10 total employment in the fishing, hunting and trapping industry was 11,431 people, an increase of 2208 people relative to 2008–09 (figure 21). This was the result of an increase in the number of people employed in the fishing, hunting and trapping sector, which rose by 66 per cent (3040 people) to 7646 people.

Meanwhile, the number of people employed in the aquaculture sector fell by 18 per cent (831 people) to 3785 people in 2009–10 (table A).

Full-time employment accounted for 74 per cent of employment in the fishing, hunting and trapping sector, with part-time employment making up the remaining 26 per cent.

Compared with 2008–09, the number of people engaged in full-time employment in the fishing, hunting and trapping sector increased by 3093 people (125 per cent) in 2009–10. Part-time employment in the fishing, hunting and trapping sector fell by 54 people (three per cent) in the same year.

In the aquaculture sector, full-time and parttime employment accounted for 76 per cent and 24 per cent, respectively.

Compared with 2008–09, the number of people engaged in full-time employment in the aquaculture sector decreased by 1162 people (29 per cent) to 2890 in 2009–10.

In contrast, part-time employment in the aquaculture sector increased by 330 people (58 per cent) to 895 between 2008–09 and 2009–10.

Males account for the major share of employment in the aquaculture and fishing, hunting and trapping industries, with 10,228 males (89 per cent) and 1203 females (11 per cent) employed in the industry in 2009–10.

By sector, 7646 people were employed in the fishing, hunting and trapping sector and 3785 were employed in the aquaculture sector. The number of females working in the fishing, hunting and trapping sector and the aquaculture sector was 912 and 292, respectively.

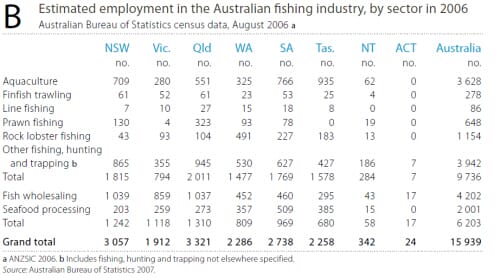

The most recent ABS Census Survey detailing employment in the fishing industry, by sector and by state, was conducted in 2006 (table B). Fishing, hunting and trapping and aquaculture activities employed 9736 people, while fish wholesaling and seafood processing employed 6203. Employment consisted of 6108 (63 per cent) people engaged in fishing, hunting and trapping activities and 3628 (37 per cent) in aquaculture activities.

The rock lobster fishing sector employed the largest number of people (1154), followed by prawn fishing (648). By state, Queensland employed the largest number of people in the wild-catch fishing sector, followed by New South Wales and South Australia. Tasmania employed the largest number of people in the aquaculture sector, followed by South Australia and New South Wales.

The Fisheries Research and Development Corporation has noted several points about the ABS employment data, including that it provides a highly conservative estimate of employment in the commercial fishing industry.

Employment in commercial fishing covers Commonwealth fishing employment and state fisheries and aquaculture.

In the Corporation’s view, data collected by the ABS are not disaggregated in sufficient detail to be useful for planning and strategic purposes. These data tend to ‘under-report employees, including through attribution of some fishing industry activities to other industries such as transport and generalised food processing’ (FRDC 2005).

Furthermore, ABS employment data do not appear to be consistent with data collected in connection with fishing vessels, fishing licences and other forms of fishing regulation.

However, the latter sources are not sufficiently comprehensive to provide a substitute for ABS data.

Until accurate information is available, the FRDC estimates that commercial fishing employment is between 100,000 and 110,000 (FRDC 2010). This figure includes people employed in the wild-catch, aquaculture and all post-harvest processes (including putative seafood components of transport, wholesaling, retailing and restaurants).