The study, published recently in journal Science, showed the shrinking size of Atlantic salmon in the River Teno in northern Finland could stem from the commercial capelin fishery.

Capelin, which are rich in omega-3s are one of favourite foods of wild salmon, but much of the capelin fishery catch is used as fishmeal for aquafeeds. The researchers note that overexploitation of capelin is an indirect way salmon aquaculture could influence wild salmon populations.

“The aquaculture industry has made important progress in finding alternative protein sources for aquaculture fish feed, and our study suggests that these efforts have not been in vain, as it seems capelin harvest may affect wild salmon populations. Globally, 18 million tonnes of wild fish such as capelin are harvested annually for domestic animal feed, so there is still work to do to further reduce the effects of aquaculture on wild fish populations,” Professor Craig Primmer at the University of Helsinki said in a press release.

“Our earlier research had shown that the age at which salmon were maturing in this river was getting younger, and consequently also the size of salmon that are spawning was getting smaller, showing ‘evolution in action’. Important for demonstrating rapid evolution, there were also changes in their DNA at a gene known to be linked with maturation size and age,” Primmer added.

“This previous research couldn’t tell us what environmental or human influences might be linked with the evolutionary changes. To understand this, we needed to link the yearly changes in the salmon DNA variation with annual changes in environmental and human-linked factors,” Dr Yann Czorlich, the first author of the research, continued. “We gathered literally millions of data-points about factors, including yearly water temperature, salmon fishing effort, and commercial fisheries’ catches of the fish salmon eat in the ocean, and compared them with our data on DNA changes in our 40-year time series”.

The impact of salmon fishery changes

In addition to the indirect effect of capelin harvest, the team also identified a direct effect caused by commercial netting of salmon in the river.

“We found that a special net type, a salmon weir, that accounts for majority of net catches, is capturing predominantly smaller fish, although net fishing is often assumed to catch larger fish,” says Jaakko Erkinaro, a research professor at Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke).

Indigenous knowledge provided an answer for this surprising result: “We discussed with local Sámi fishers who have fished with salmon weir for decades, and they explained that, compared to other net types, salmon weir has smaller mesh size, is used later in the season and mostly in shallower waters, which increases the catch of smaller salmon. This likely explains the result,” Erkinaro continues.

Weir fishing has decreased in recent years, and simultaneously, the proportion of small, early maturing fish in spawning populations has increased.

“Our finding that there are different forms of fishing acting in opposite directions at different phases of their life-cycle highlights new challenges for salmon management, but also the value of having unique long-term data series at our disposal,” noted Erkinaro.

Methodology

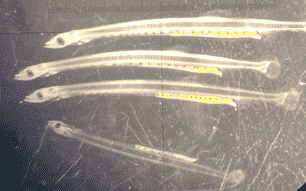

The research team examined scale samples from salmon over a 40-year period and linked the variation of a gene that determines salmon reproduction age and size, with the effects of different fishing methods. The scale samples used for the study came from a unique long-term scale archive maintained by Luke. The archive keeps samples from more than 150,000 salmon collected by trained, volunteer fishers since the 1970s from the River Teno, one of the most prolific salmon rivers in Europe. The scales were used to determine the age structure of the salmon population. They were also the source of DNA for genetic analysis.