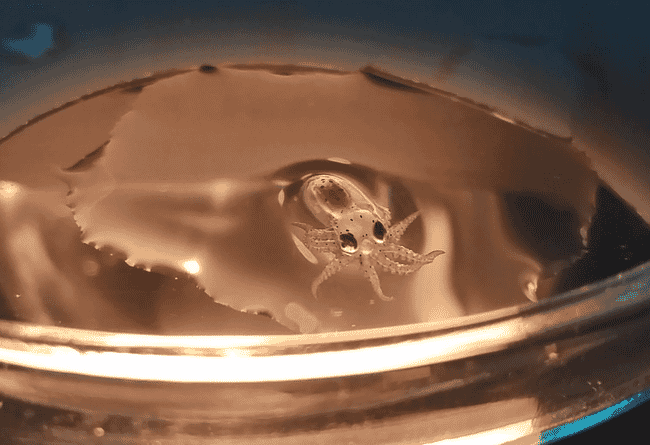

So argues the Galician firm, which has devoted eight years of R&D to closing the lifecycle of the octopus. The first breakthrough, relating to larval rearing, was made possible thanks to scientific research initiated in 2014, through the OCTOWELF project. Since then, they have managed to breed five generations of octopus in captivity, all stemming from the offspring of a single captive-born female, who was christened “Lourdita”.

“We are the first company in the world to close the life cycle of the octopus, achieving the fifth generation of octopus reared in aquaculture. It is a pioneering project that will be at the forefront of best practices in animal welfare and environmental sustainability,” a spokesperson told The Fish Site.

As their research has progressed, so has the prospect of making commercial octopus aquaculture a reality. And, in November 2021, the company unveiled ambitious plans to invest €50 million in a 3,000 tonne capacity farm in Gran Canaria.

“The construction of an octopus farming plant in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria represents yet another step in the extensive and complex scientific challenge of guaranteeing a sustainable yield of the common octopus, a food in growing global demand for its extraordinary healthy and nutritional properties,” the company proclaimed.

Galician roots

Whatever your views about octopus farming, it’s fitting that the first company to achieve this comes from Galicia, a region famed for its seafood and which is awash with pulperias – restaurants that specialise in all dishes octopus.

While, traditionally, the octopus eaten in these restaurants were sourced from the local coastline, 80 percent of them are now imported, largely from Morocco and Mauritania. Globally, around 350,000 tonnes of octopus are captured in the wild each year, and demand for the species continues to rise, as do prices for the invertebrates.

While short-lived, octopuses grow fast, produce lots of offspring and fetch a good price on the market, making them very appealing to commercial aquaculture companies. However, the fledgling octopus farming sector has struggled to overcome a number of bottlenecks, including the difficulty of incubating, hatching and raising octopus larvae in captivity. This has meant that ranching wild-caught octopus, is more commonplace than farming. Nueva Pescanova rightly points to the fact that their closed-cycle production could help to meet growing demand while also reducing pressure on wild stocks.

“Octopus aquaculture is the possible and necessary solution, endorsed by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), in its 2022-2031 Blue Transformation strategy,” they explain.

The company adds that they could also help to restock wild populations in coming years, through releasing juveniles back into the wild.

“With this project we are studying the possibility of helping to repopulate the species in the future,” they note.

Welfare concerns

One of the most common criticisms of octopus farming is that – due to their solitary and territorial nature in the wild, as well as their relatively high levels of intelligence – they are not suited for mass production in an enclosed system, such as Nueva Pescanova is planning. It’s an ethical question that’s hard to dismiss.

However, according to Nueva Pescanova, they have made substantial progress towards ensuring that the cephalopods can co-habit in captivity, thanks to research they’ve conducted in collaboration with IIM-CSIC, National Autonomous University of Mexico, CIIMAR, University of Malaga, University of Vigo, the Spanish Institute of Oceanography (IEO) and Samertolameu.

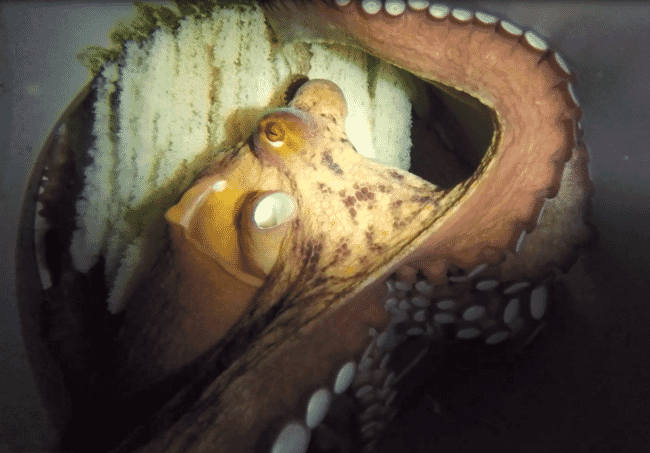

© Tania Rodriguez Gonzalez

According to the company, population density studies developed by IEO, have “proven how octopuses adapt normally to group living environments without aggression due to territoriality”.

When The Fish Site was given rare access to the Pescanova Biomarine Centre (BPC), in Galicia, we were able to see five impressive octopus broodstock co-habiting in one tank, with no signs of fighting or injury, nor obvious signs of distress.

According to the company, the adaptation of the octopus to the pool habitat “has been achieved by applying an advanced zootechnical solution, called the EcoBiological Production System, which applies the natural and specific conditions of the species in the wild to the productive culture”.

“These conditions allow the octopus to reduce movement by propulsion (associated mainly with a response of danger or flight from its multiple predators) and to prioritise its more natural and habitual movement through its arms, thus avoiding collision damage and significantly reducing the animal's stress,” they say.

It’s a pioneering system, developed by the research team at Pescanova, and the company says that it has been providing excellent results in both its turbot and octopus production facilities in terms of growth and survival.

Most recently the company has been working with researchers from the Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas (IIM-CSIC) to determine the presence or absence of stress hormones in cephalopods, in order to help maximise farmed octopus welfare.

The new facility

The new octopus farm is due to be built on a 50,000 m2 plot in the Port of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria – where the water temperatures are ideal for farming. Nueva Pescanova points to a number of features set to ensure a high level of energy efficiency, including PV panels, as well as advanced connectivity to enable high tech production methods that are commonly referred to as “aquaculture 4.0”.

The final design of the Gran Canaria facility is still a work in progress – one that will be dependent on the results of ongoing research.

“Certain studies and basic projects have already been advanced, but the execution project, where all the technical aspects will be detailed, is currently being prepared. With full transparency and legal rigour, they will be available to citizens during the mandatory public exposure period in the competent bodies,” the company explains.

Octofeeds

The dietary requirements of octopus have been another cause for concern raised by environmentalists, as they traditionally require high levels of marine ingredients.

However, Pescanova aims to develop its own feeds, based on the offcuts of fish from the other parts of its substantial seafood business, which includes farming shrimp in Ecuador, Guatemala and Nicaragua, farming turbot in Spain and a fleet of over 60 fishing vessels operating in the waters of Namibia, Angola, Mozambique and Argentina.

“Our research is making progress in solving the environmental challenge of feeding farmed octopus with maximum sustainability criteria, in accordance with European guidelines. Specifically, based on the diet model developed by the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) for the Yucatan red octopus (Octopus maya), a feed is being developed for farmed common octopus that uses the parts of fish, caught or farmed, that are not intended for human consumption; a circular economy solution that helps to avoid overexploitation of fishery resources,” notes Pescanova.

Moreover, the company points out that the PBC is researching the substitution of animal raw materials for others of vegetable origin, such as spirulina, a microalgae whose protein component accounts for 70 percent of its biochemical composition.

Following the success of My Octopus Teacher – a wildly popular and painstakingly made documentary which was aired on Netflix and introduced the animals’ apparent intelligence to the wider public – there is little doubt that Nueva Pescanova’s plans will continue to raise objections.

However, it is also apparent that – as long as octopus remain on the menu – farming is likely to offer a better solution than ranching or capturing the cephalopods.

“Our octopus aquaculture project is necessary to protect a species of great environmental and human value,” the company concludes.