© Marcela Salazar, Benchmark Genetics

Nofima scientists have collaborated with colleagues at Benchmark Genetics in Colombia and Norway to show that genomic selection can be used to boost the ability of shrimp to resist the highly lethal and contagious WSSV disease. More than 80 percent of individuals in the best genomically selected families survived when challenged with the disease. Like vaccinating a population against disease, having animals with this level of resistance in the shrimp population would likely be sufficient to provide a herd immunity effect, greatly reducing the impact of the disease. Genomic selection holds great promise for improving resistance to other diseases as well, as is currently being implemented by Benchmark Genetics.

Global viral pandemic in shrimp

White spot syndrome virus disease causes billions of dollars of losses for shrimp farmers all around the world. The disease spreads quickly and preventative measures for contagion have proven ineffective.

Primitive immune system

Crustaceans lack immunological memory, and therefore vaccination for boosting the immune response has limited success against the virus. Stimulation of the innate immune system shows some promise but is so far unproven in the field. We know that some animals are inherently better able to resist or tolerate the virus than others, but we still do not understand the specific mechanisms underlying these differences. It is possible to breed animals with higher resistance to WSSV through conventional family selection, but progress has been slow. The industry desperately needs better solutions to prevent mass mortality caused by this aggressive pathogen.

Genomic selection

Genomic selection is a recent methodology, originally developed for livestock improvement, employing the latest in DNA sequencing technologies. Breeding and genetics scientists at Nofima have worked with Benchmark Genetics on these technologies in whiteleg shrimp (L. vannamei). Instead of relying on pedigree relationships for estimating the breeding value of individuals we used DNA sequence data to estimate the genomic relationships between individuals at tens-of-thousands of positions throughout the genome of the organism. This technology gives us a more precise means of predicting the breeding value of potential broodstock in the population (known as a genomic breeding value in this instance).

A major advantage of genomic selection over traditional selective breeding for a trait like viral disease resistance is that it allows us to more accurately predict which breeders have the best overall resistance genotype without exposing the candidate breeders themselves to the disease.

First application to genetic improvement of crustaceans

In the GenomResist research project, funded by the Research Council of Norway, we tested how effective genomic selection would be for improving WSSV resistance in whiteleg shrimp.

Nofima and Benchmark set up an experiment using two source populations developed by Benchmark Genetics Colombia, one already mass-selectively bred for several generations for high white spot syndrome virus resistance the other primarily selectively bred for fast growth rate. These animals were randomly separated into two groups: a test population which was challenged with the virus and a candidate broodstock population that was kept under high biosecurity.

We achieved a strong coverage of every position across the shrimp genome, to give us accuracy for the genomic selection, by compiling an array of DNA tests (single nucleotide polymorphisms), including recently discovered tests that were developed as part of another project for Benchmark Genetics. Data and samples for DNA testing were collected from the individuals in both populations. Information about the survival of shrimp following the challenge test with the virus was combined with the genomic relationship data from the DNA testing and used to predict genomic breeding values for survival for individual broodstock (animals not exposed to the virus).

© Nick Robinson, Nofima

We then selected and mated broodstock to produce two different populations of shrimp, one with high and the other with low genomic estimated breeding values. The survival rates of these two populations, and offspring from “randomly” mated parent stock, were compared in a challenge test.

Survival booster

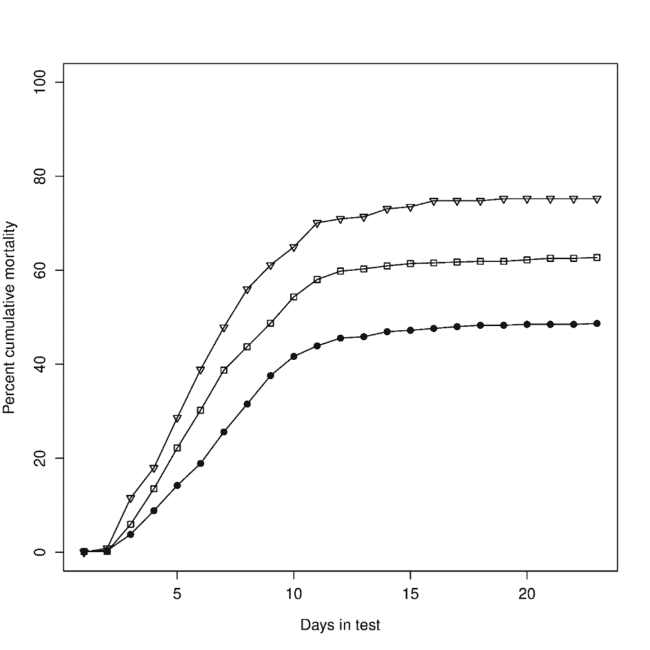

The results demonstrated that the average survival of shrimp families increased from 38 percent to 51 percent after only one generation of genomic selection for high WSSV resistance.

Percentage cumulative mortality plotted over days in challenge test for animals in the high- (closed circles), random- (open squares) and low- (open triangles) genomic breeding value populations. © Nofima

Implications for shrimp production

Our collaboration has demonstrated that relatively high levels of genetic improvement can be achieved for survival to WSSV in whiteleg shrimp after just one generation of genomic selection and have shown that genomic selection can be used to improve survival to levels that have commercial relevance for the industry. Compared with conventional methods of selective breeding for disease resistance, genomic selection is significantly more sensitive at predicting, and better able to utilise, information about the underlying genetics affecting resistance. Like the effect of vaccinating members of a population, we expect that high levels of immunity in the best populations will have a “herd immunity effect” because highly resistant animals will no longer infect other animals. The inoculum pressure is likely to be lower in commercial ponds than it was with our experimental challenge tests in tanks, and the best families in our high genomic breeding value population showed survival of over 80 percent. Levels of 70 percent survival have been shown by other researchers to be sufficient for keeping another viral disease (caused by taura syndrome virus) under control in shrimp.

By using genomic selection, we have demonstrated that we can rapidly increase the level of disease resistance in whiteleg shrimp. Benchmark Genetics now uses this tool to offer farmers shrimp populations that can survive in the presence of WSSV. Genomic selection also holds great promise for the improvement of other economically important traits in shrimp and other aquaculture species. The research shows that genomic selection could go some way towards solving this multibillion-dollar problem for the shrimp industry in the future.

Further information

The full study, which was published this week in Scientific Reports, can now be accessed here.