Marine aquaculture in Greece is an important sector for the country and the Mediterranean in general, in terms of production volume and value. Favourable environmental and climatic conditions, existing infrastructure as well as long-standing experience and scientific know-how have made aquaculture one of Greece's key productive sectors. With a multiannual national strategic plan for aquaculture in place, competitiveness and sustainability are likely to be further enhanced.

A key player in Greece's aquaculture is Selonda Aquaculture SA, one of the largest marine fish producers in the Mediterranean. Pavlina Pavlidou has been part of Selonda for 24 years and acted as Hatcheries Division Director for 11 years. Currently working as R&D and Technical Consultant, Pavlina is a firm believer in the importance of breeding programmes and genetics for the future of Mediterranean aquaculture. She is also keen to stress the significance of the added value for Selonda of having its own hatcheries, and that collaboration between hatcheries and on-growing farms is vital to fulfil the needs of grow-out and continuously improve fry quality.

Briefly describe your aquaculture career

I studied biology at Aristotle University in Thessaloniki in Greece and completed my MSc in aquaculture from Stirling University in Scotland, before joining Selonda in 1994 as a technician in the only hatchery they owned at the time, in Epidaurus. After four years working in all the departments (live feed, broodstock, larval rearing, nursery and transportation), I was sent by the company to Italy to supervise the hatchery of Marina Maricoltura Ltd, which Selonda wanted to acquire at the time. A year later, upon returning to Greece, I started coordinating the operation of three hatcheries that Selonda owned back then - Epidaurus, Managouli and Sagiada.

In 2005, Selonda acquired the Psachna Hatchery in Evia, Greece and the Larymna Hatchery in central Greece. The hatcheries division expanded and I become its director. I stayed in that position for 11 years (2005-2016), taking production up to 165 million fry in 2016. After 22 years working in production, at the end of 2016 I stepped into a more research-oriented role as R&D and Technical Consultant. My target is to develop the company’s breeding programme and implement recent technological advances in all production areas.

What inspired you to start in aquaculture?

I chose to do my biology thesis, which was published in Muscle & Nerve, in neurobiology, but I realised that my real desire was to work outdoors, close to nature. At the same time, I got my first scuba diving certification, which gave me the opportunity to admire the marine world with all its mysteries and miracles.

I started looking for work that would fulfil my ambitions and found that Greece, my own country, was actually the champion of Mediterranean aquaculture. My inspiration to start working in aquaculture was a combination of many factors - a desire to work close to nature with my scientific background and the benefits of aquaculture itself that provided me with the idealism that a young person needs to be attracted to a job.

What's the most unusual experience you've had in aquaculture?

It was during a conference on Hainan Island in China when we visited an aquaculture area as part of a field trip. We went to a big, floating city with no drinking water or sewage system, with chickens, pigs, dogs and babies all around. The water was yellow brown and it was impossible to tell whether there were any fish in the cages, while a big container ship was selling trash fish meal to feed them. These extreme conditions were a shock to me, and made me understand the wide range of conditions under which aquaculture is performed around the world.

What's the most interesting experience you've had working in the sector to date?

During the long course of its development, Selonda acquired a considerable number of farms and hatcheries that belonged to smaller companies. Our hatcheries team approached and analysed all environmental factors, particularities and historical results of these “new” hatcheries and, at the same time, incorporated necessary changes to improve performance.

The most interesting experience for me was observing this transition taking place over and over again, resolving different problems of different origins every time, and always resulting in better technical and economical results. This was very inspiring and encouraging because it means that even though we don’t have all the answers to the different problems that may occur during fry production, we can always achieve better technical, and consequently economic, performances, if we work methodically and systematically with respect for each system.

What are the advantages of Selonda having its own hatcheries?

The fry output (apart from the portion assigned to customers) of the hatcheries is programmed to fulfil the exact demands of on-growing in all aspects – ie species availability, timing (very important), size of batches, specific MW for specific sites. The target is to enhance the results of the on-growing, where the highest production cost occurs. It also guarantees high quality fry: the on-grower receives a product with specific quality characteristics and therefore knows what to expect in terms of growth performance and how to handle it to maximise the benefits.

Moreover the hatcheries department continuously follows fry performance during on-growing, spots potential problems and proceeds to corrective actions that can be tested and followed. The system "feeds" itself towards a common beneficial direction.

Last but not least our grow-out operations receive high quality fry at the production cost and therefore on-growing costs are reduced.

What are some of the key issues when it comes to coordination between hatcheries and on-growing?

Good communication, collaboration and logistics are all crucial, but these are just practical prerequisites. What counts in such an operation is to always have the big picture in mind, to realise that hatcheries and on-growing are just stages of the same uninterrupted procedure, where the most important issue is to continually preserve and enhance fish health, robustness and therefore growth.

In Selonda, the results of the hatcheries' department are not assessed at the door of the hatcheries, but at the packing station. Of course, it's very important to have the scientific knowledge and experience to evaluate problematic areas, identify the causes and spot the exact parameter or stage of the chain that needs improvement. It is the value of this experience and knowledge that can make an integrated company much more than the sum of its parts.

How important are sustainability concerns to you and how do you address them in your work?

Sustainability is a crucial prerequisite for the viability of aquaculture. All stakeholders should focus on it and work together to ensure a lighter footprint of the aquaculture sector. The balance between extracting from the environment and giving back to it needs to be positive. This is collective work and involves all players of the chain, from raw material use for feed manufacturing to the minimisation of carbon dioxide emissions during production, transportation even adopting animal welfare. In my work, we address sustainability by producing high quality fry. This guarantees that during grow-out, there will be low mortalities, high growth and consequently a low FCR. All land-based systems in our hatcheries also have the latest technology and are Global Gap certified.

What innovation do you think has the most potential to change aquaculture?

Genetics through breeding programmes can make a big difference. Selecting for growth, low FCR, disease resistance, robustness, metabolisation of plant-based nutrition, fillet yield and so on, can contribute to the sustainability of the industry and company profitability. However, this takes time. Improvements through genetics come from a long-term commitment that is required in order to obtain the benefits of recent genetic research. Vaccines can also produce promising changes. Today's vaccines have already significantly reduced mortalities and new ones, especially for bream parasites and Aeromonas for bass, can lead to even further reduced mortalities.

Are there any individuals or organisations in aquaculture who you've found particularly inspirational?

Two individuals have been particularly inspirational for my career. The first is Peter Kelsey, manager of the first hatchery of Selonda in Epidaurus. He was my first boss when I was hired in 1994 and an inspiring British marine biologist who loved aquaculture. He came to Greece from Ecuador where he worked in a shrimp hatchery. In Selonda, he found the mentality he liked as well as the prospect of development and growth. He helped build the hatchery, stayed for 7-8 years as manager and subsequently worked as an engineering consultant of the company for all hatcheries in Greece and for Selonda's collaborations abroad. I admired the depth and broadness of his knowledge in all areas of fry production – from biology to engineering and mechanics. I remember Peter playing his harmonica in the larval rearing area, late in the afternoon at the end of the hatchery morning shift. Unfortunately he died in 2006 from cancer, at the age of 44.

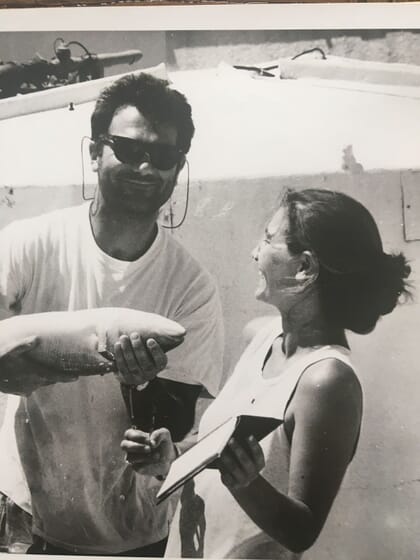

The second person, who also happens to be my husband, is John Stefanis, the founder of Selonda. John is a visionary, one of the pioneers who saw the future of aquaculture in the Mediterranean and opened the road for the sector to become the industry it is today. John is passionate about aquaculture. He is an open-minded businessman who not only created Selonda but also made it one of biggest producers in the Mediterranean with an international reputation. John has a rare personality with inclination towards business innovation and leadership. He analyses conditions in depth and has the courage to materialise his dreams.

Have you faced any particular challenges as a woman in aquaculture, and have you seen the opportunities improve in recent years?

Usually, women work in hatcheries and especially in the live feed and larval rearing departments, where detailed work is crucial. Sometimes women head these departments, and although more rare, you might meet them in positions as hatchery managers. All the women working in production are dynamic and determined because the work is difficult. Even physical strength plays a role and the environment can be hard. Climbing the hierarchy, you meet fewer and fewer women, and I can definitely say that for many years I was the only woman in the room when attending Selonda's management meetings.

It is a challenge being the only woman in any group of people with big responsibilities. I think the only way to get ahead is to believe in yourself and function as a professional, not as a woman. Recently, conditions and attitudes have improved and as a consequence, more women are becoming involved in aquaculture. This is very positive because we need the intelligence, skills and talents of women. This participation now needs to be substantial in high level jobs as well, for example as Heads of Divisions or members of Boards of Directors, General Managers, CEOs... only then will we be able to say that things have definitely improved.

What advice would you give to women looking to start a career in the aquaculture sector?

First of all, for a woman or a man to pursue a career in aquaculture, he or she must deeply love the idea of fish culture and the work that it involves. It is a difficult sector with a lot of particularities and these are almost impossible to withstand if you don't love fish culture. For a woman in particular, it is very important to have deep knowledge of the field in which she is involved, to never stop acquiring new knowledge, and to use her expertise as a shield against the difficulties she encounters. As in all fields, and regardless of whether we are talking about a man or a woman, the professional has to be determined through strong will, the ability to adjust and to never give up his or her dreams.

What outstanding challenge would you most like to solve?

Even though there has been tremendous progress in most areas of aquaculture, the public perception of its products remains unresolved. For example, it is very common for fish restaurants to advertise the quality of their fish by emphasising the fact that they are "wild." In Greece, the largest producer of sea bass and sea bream in the Mediterranean, many people know very little about aquaculture and most of them don't trust the quality of aquaculture products. There are marketing campaigns from time to time but they are erratic and have not established in consumers' minds the premium quality of aquaculture products. In my view, this is an outstanding challenge – to design innovative and smart systematic marketing techniques to increase consumer confidence in aquaculture activities and products.