© Pure Algae

Pure Algae’s CEO and founder, Esben Christiansen, traces back the company’s origins to his youth in rural Denmark. Growing up near an idyllic lake, he learned that the ecological balance of his childhood haunt was threatened by nutrient runoff, which led him to pursue a career in bioremediation.

While his early research focused on using bacteria for this purpose, a visit at James Cook University in Australia introduced him to the power of seaweeds, which he saw as a superior solution for the problem he was trying to solve.

As he explains: ”With bacteria it's very hard to reach scale. In Australia, I saw land-based seaweed production could not only help you reduce nitrogen and phosphorus levels in the water, but you would actually gain the seaweed as a valuable biomass. I understood this was not just bioremediation. This was a business model.”

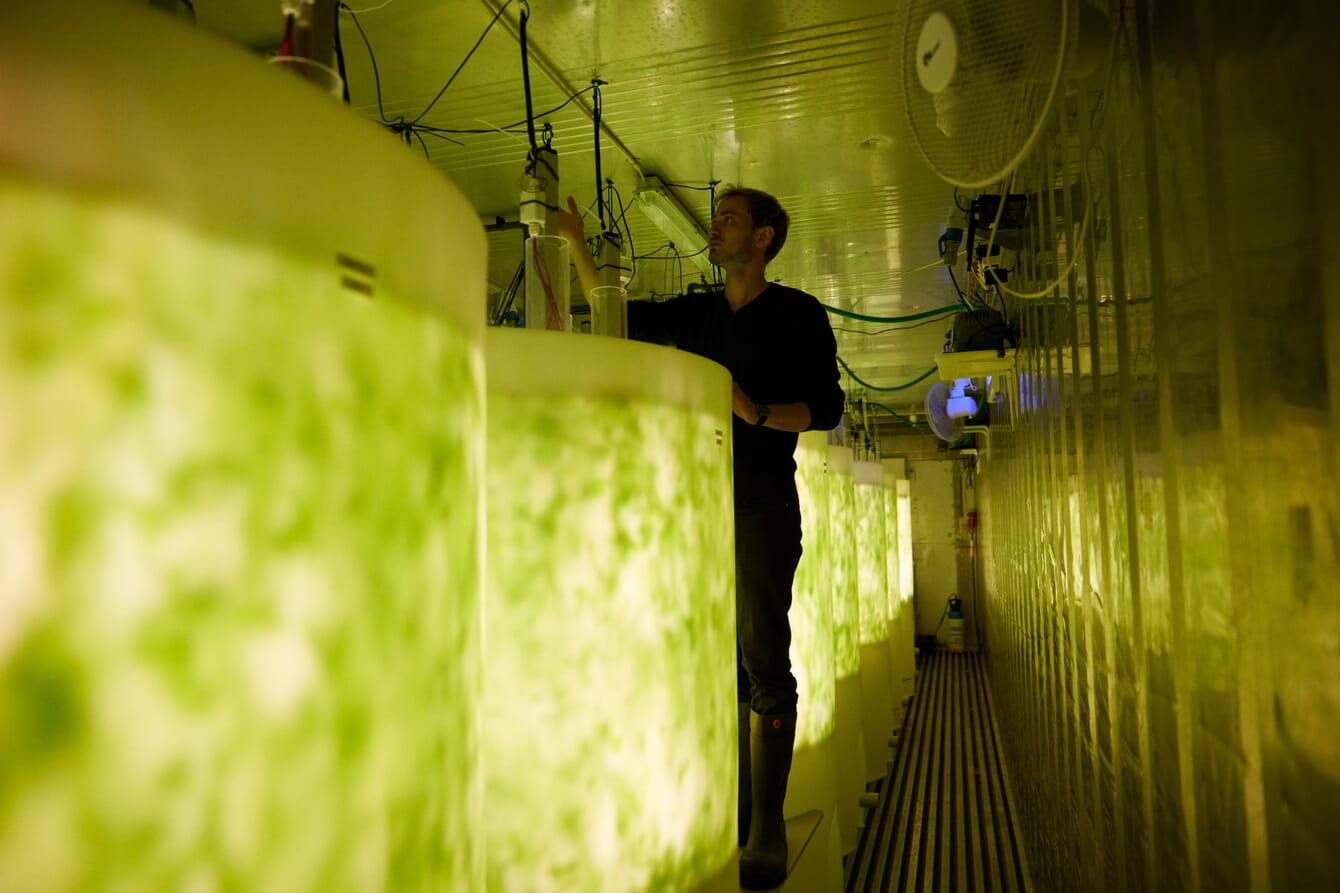

Back home in Denmark, Christiansen’s early failed seaweed cultivation trials taught him that data and control would be the keys to unlocking value. Testing the production process one parameter at a time led to the design of a novel photobioreactor system to optimise seaweed production.

The photobioreactor has since evolved from a container-based system into a vertical unit. As Christiansen explains: “In order to stay true to our purpose of bioremediation, land-based RAS would have to be our key customer segment. So we started selling our PBR as a plug-and-play container system. But we quickly learned that RAS farms are tremendously big. The scale didn’t match; we could not install a hundred containers.

“So we ended up going vertical – our latest unit is 3.5 m tall. This way, surface area is no longer a limiting factor, and we obtain extremely high yields, with energy use per kilogram of seaweed produced equivalent to that of regular lettuce produced in vertical farming. In our original raceway system, a large proportion of the light was reflected on the surface. If you want to have the full energy efficiency of a seaweed system you really need to have the light in the water. And that’s key to our patent: it ensures homogenous and cost-efficient light distribution within the tank.”

Christiansen does not deny that a photobioreactor adds costs compared to a raceway at a sunny location. But as he sees it, those costs may be outweighed by the predictability and consistency of a system that has close synergies with the RAS production model.

“It’s hard to build a business if you only get a high output when the sun is shining, but your fixed costs stay the same," he explains.

“With a RAS based on full control, you also need a remediation system that allows full control. Our PBR can connect to the RAS farm’s pipes, without the need to spend more energy on, for instance, temperature control. Control in the water brings equilibrium in the balance sheet," he adds.

© Pure Algae

Converting emissions into revenue streams

Currently, RAS farms use degassing filters to remove nitrogen. The first filter removes a significant portion, but efficiency goes down exponentially with each additional filter, making further removal increasingly expensive. As a result, most RAS farms allow the final ten percent of nitrogen to be released into the sea. Producing 1,000 tonnes of fish per year generates about 45 tonnes of nitrogen, which means that with 90 percent removal, 5 tonnes of nitrogen still end up in the marine environment each year.

This, Christiansen is adamant, means that there is willingness to remove even more.

As he sees it, “this amount of nitrogen can be turned into 100 tonnes of dry seaweed. We offer a system that turns emissions into revenue streams. It's not just a photobioreactor. It's a fully functional system, including a drying module that can be connected to the excess heat of the RAS farm. We are looking at any and every type of emission. Because the more we can draw on the synergies, the more competitive a product the RAS can get.”

Some RAS producers have expressed interest in feeding the seaweeds back to the fish or other aquatic species, while for others, Pure Algae is taking up the role of value chain facilitator, connecting potential producers with biotech firms with specific seaweed needs. The company also sees a market in pure-play seaweed farms which need a controlled production unit for a unique high-value species.

At the moment, though, it is the laboratory setups for seaweed producers, RAS farms, researchers and biotech companies who are conducting strain selection and growth optimisation that are proving to be life-affirming for the company. Christiansen admits getting RAS farms to actually commit is a longer-term project. “RAS farms require a lot of documentation. They want a five year track record before any decision,” he reflects.

“We are very convinced that we can make a good business proposition, even for the most conservative of them, but for now we need to appeal to progressive RAS operators. Because we need someone who is not just testing this on the scientific elements, but also willing to actually implement it,” he concludes.

© Pure Algae