Nofima has been investigating the use of spectroscopy, through the Spectec project, in a bid to improve and develop new and better rapid measuring methods using light.

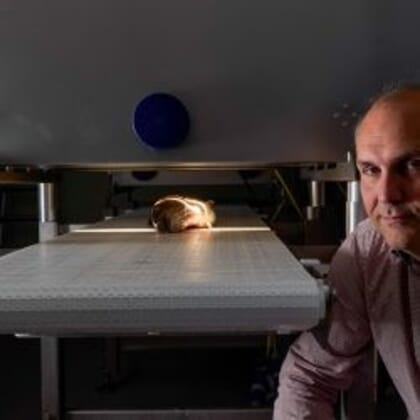

“We have been working for some years to develop an efficient method of ascertaining quality that can be used on both white fish and red fish, like salmon and trout. Now we have hit the jackpot, and we hope to launch a prototype sorting machine for use in the industry in about a year’s time,” says senior scientist Karsten Heia.

© Audun Iversen, Nofima

“In simple terms, spectroscopy is a method of measuring using light. Light is passed through a fish, and we have devised a way to work out how much blood is in the fish muscle, based on how much light is reflected back. Various elements inside the fish absorb light, and we can now identify how much of the light loss is caused by, say, blood.”

Equally it is useful for producers of red fish to be able to know the fat content of fillets and whether they contain melanin – which spectroscopy can also cover.

“We can scan white fish whole, ie without having to cut them open. We know that 30–40 per cent of the fish landed have a high percentage of residual blood in their muscles. By identifying these fish at an early stage in the production line, they can be processed differently, ensuring maximum profitability from each individual fish. It is very expensive to send inferior fish for filleting only to discover the real quality there,” Heia explains.

Consumer preference

Consumers expect high-quality white fish to be white. A pink or red fillet means too much blood has entered the muscle. This generally occurs because of stress or injury during capture or slow processing on board. Either the blood in the fillet must be cut out or the fillet must be sorted for a different, less profitable use. Both require additional resources, making production more expensive and reducing profitability.

© Audun Iversen, Nofima

“Blood in fillets is really only a matter of aesthetics. The fish tastes exactly the same, but consumers are not willing to pay as much for it. Therefore, fish with blood in their muscles are best suited for salted fish production or use in fried fish products. If the quality can easily be ascertained before the fish enters the filleting line, the fish can be processed on the basis of the price it can command in the market. This system will also make it easier to reward fishermen who land good-quality catches,” the scientist adds.

Salmonid issues

Red fish like salmon and trout are a bit more complicated, since both the flesh and the blood are red, so here the method works best on fillets.

“With red fish it is important for the producers to know the quality before further production, for the same reasons as for white fish. Blood in the muscle oxidises and gives the meat a less attractive colour. For example, if you make smoked salmon out of a filet that contains a lot of blood, there will be black spots in the final product. This is normally not detected until you start slicing up the salmon. In other words, you will have made a product you cannot sell at full price, even though you have used exactly the same resources to produce it as the ones you can sell at a normal price,” says Heia.

In the past, producers have resolved this by buying 20–25 percent more raw material than they need, because they know that a certain percentage will have to be sold at a lower price. With spectroscopy, they can determine the content of fillets before they start smoking or curing them.

Improving catch quality

“This method can also be used to improve the quality of wild-caught fish in the fishing industry in general. There is nothing to indicate that quality will improve by itself, as long as the fishermen are not rewarded for investing more money in catching operations to ensure better quality. Using this method, it is possible to sort out fish on landing that have too much blood in the muscles, meaning fishermen who deliver good quality catches can be rewarded. If the fishing industry only received good raw materials, production could run much more efficiently and with higher quality products,” says Heia.

The project has now entered a new phase where the equipment suppliers Maritech and Lillebakk Engineering, supplier of hyperspectral cameras Norsk Elektro Optikk, as well as representatives from the white fish industry Havfisk AS and Lerøy Seafoods have teamed up with Nofima to turn this method into a commercial product by the middle of 2019.