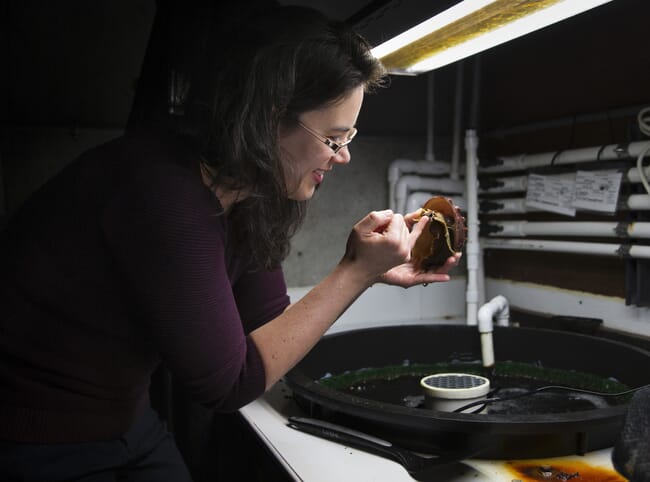

Six abalone species — red, white, black, green, pink and flat abalone — are listed by IUCN as critically endangered © Joe Proudman, UC Davis

These listings were based on a West Coast abalones assessment led by Laura-Rogers Bennett of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, or CDFW and University of California, Davis.

Six species — red, white, black, green, pink and flat abalone — are listed by IUCN as critically endangered. The northern abalone, also known as threaded or pinto abalone, is listed as endangered.

The IUCN Red List is considered the world’s most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of species. While the listing does not carry a legal requirement to aid imperilled species, it helps guide and inform global conservation and funding priorities.

Red abalones have been a mainstay of West Coast shellfish aquaculture industry © Cynthia Catton, California Department of Fish and Wildlife

“We hope this listing will highlight the dire status of these species,” said Rogers-Bennett, a senior environmental scientist with the CDFW, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine’s Karen C Drayer Wildlife Health Center and Bodega Marine Laboratory. “I hope this assessment will trigger a real concern and investment in these species now before the population numbers get so low that they’re really hard to bring back from the brink of extinction.”

Rogers-Bennett collaborated with Howard Peters of the Department of Environment and Geography, University of York, UK, who led the global abalone assessment. They worked with researchers who contributed their data and reviewers who are species experts.

Abalone conservation lessons

Abalones have long provided nourishment, cultural significance and ecological benefits for people, wildlife and the environment. Red abalones have been a mainstay of West Coast shellfish aquaculture industry with a beloved recreational diving fishery in Northern California. But the world’s abalones are in decline through over-exploitation, disease and climate change.

Along the West Coast, these giant sea snails with their iridescent shells have been hit particularly hard by overfishing, the decline of the kelp forest, warming ocean temperatures and other impacts.

The UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory hosts the white abalone captive breeding programme © UC Davis

The UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory, School of Veterinary Medicine and CDFW have been pioneering work to help protect abalones. This includes the federally endangered white abalone captive breeding programme and several studies involving the red abalone, ocean acidification, climate change and aquaculture.

“Let’s capitalise on what we’ve learned with the white abalone and get these programmes up and running now,” said Rogers-Bennett. “These are things we could be preparing for now that could help protect these species in the future.”

She notes that scientists have yet to learn how to successfully spawn the black abalone, which is federally listed as endangered. Having a collection of threatened abalone species could be a step toward establishing conservation programmes for the future.

Having a collection of threatened abalone species could be a step toward establishing conservation programmes for the future © UC Davis

Key impacts to West Coast abalone

- White abalone: Overfished nearly to extinction, the Bodega Marine Laboratory leads a captive breeding programme for the recovery of this federally endangered species.

- Black abalone: Also federally endangered, overfishing and withering syndrome disease were key to their decline. A debris flow in January 2021 following the Dolan fire smothered thousands while rescue efforts successfully relocated 150 individuals.

- Flat abalone: Their narrow geographic range used to stretch from Monterey, California, to the Oregon border but has shifted slightly north with ocean warming. That shift brought them into Oregon, where they were overfished.

- Red abalone: The basis of a thriving recreational fishery until its closure in 2018. The closure followed a marine heatwave that set off a devastating chain reaction: loss of sea stars, an explosion of purple urchins and collapse of the kelp forest.

- Green abalone: In low abundance, with some resurgence around Catalina Island.

- Pink abalone: Once a major contributor to commercial fisheries, the species is now in low abundance in Southern California and Baja.

- Northern/pinto/threaded: Commercial fisheries closed in the 1990s with only subsistence and personal-use fisheries open in Alaska and stable populations in northern British Columbia. Listed as endangered in the United States and Canada.

Abalones need kelp

Rogers-Bennett said restoring kelp forests and reducing climate impacts are key to helping abalone recover. Kelp is their main food source, and its decline is intricately linked with theirs. When weakened by starvation, species are more susceptible to environmental changes like landslides following fires, ocean acidification and increased storms.

“These populations’ vulnerabilities have increased due to climate change, and that’s what’s pushed them into threatened categories on the IUCN Red List,” she said.