Lev has persuaded the company to pivot towards bioremediation © Seakura

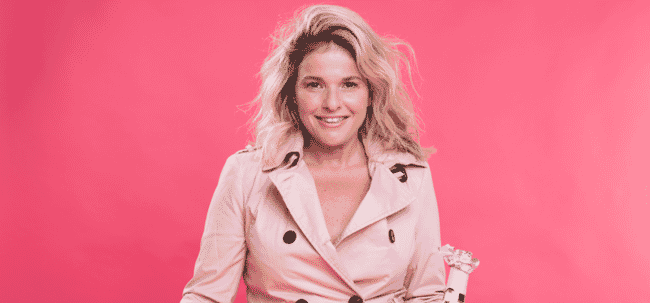

Efrat Lev, who’s been CEO of the Israeli firm since January, explains why the company has pivoted its business from growing seaweed for the food sector to this innovative new use.

While her original background is in PR, Lev decided to join the seaweed sector after her own tech startup lost key personnel in the wake of the 7 October attacks in Israel and was unable to continue.

“I’ve known Yossi Karta, the founder of Seakura, for over 13 years. When I founded my tech startup over five years ago, Yossi was my second investor. Right after 7 October, I had to freeze all activity in my startup, two of our teammates had to enlist in the army, my COO had to move down south to help protect her family and friends, and our intern was killed in the Nova party,” she recounts.

Karta decided to bring her on board.

“I told him that I have absolutely zero understanding in seaweed or aquaculture, and I don’t want to let him down. He replied that he trusts me, and he needs me to start ASAP. So here I am,” Lev reflects.

A radical pivot

At the time Seakura’s operations focused mainly on the land-based production of Ulva and Gracilaria seaweeds.

“The concept was to sell our super-premium biomass to the food industry. Seakura also created a line of food supplements and tried to obtain clients also in the cosmetics industry in South Korea for the biomass,” Lev explains.

However, on joining the company, Lev decided that they should radically change their focus.

“Although I did not come from a seaweed or aquacultural background, I knew business, and I knew the importance of focus in general, especially when it comes to your product or service,” she recalls.

“I gave myself a single month to understand the essence of growing seaweed as a business. The cost of growing was super expensive, the market of Ulva in human food sector was somewhere between the bottom of the food-chain and nowhere, operational costs where extremely high, and to keep a company going in the same direction was simply not making sense,” she adds.

As a result she sat down with CTO Dr Yossi Tal, who had been a professor in the University of Maryland for almost 10 years, to find out more about how seaweed works and what its biological traits are.

“Something began to resonate with me: seaweed is a sponge – a biological sponge – so we should look for a market that needs a sponge to absorb nutrients from saltwater bodies,” Lev explains.

In order to test this theory she decided to concentrate the company’s full strength on a pilot project that they had been tentatively developing with the Israeli ministry of agriculture.

“Seakura’s previous management did not believe in the pilot: they wanted to keep their obligations but keep the company’s focus on other areas. I dropped everything Seakura was attempting to work on at the time and took that pilot as a proof of concept (POC) to reach one local full-scale project with an Israeli desalination plant,” notes Lev.

“I knew that if we did that – we can move into the massively growing global desalination market. Within 6 months, we not only reached our POC goals, and one local full-scale project in the making, but we also established a partnership with a local port to absorb heavy-metals and clean pollution,” she adds.

© Seakura

Early success helped Seakura to secure a partnership with Mekorot, Israel's National Water Company, and complete a pilot project that proved their technology's effectiveness in removing nitrates, heavy metals and phosphorus from desalination plant brine. This pilot was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture and approved by the Ministry of the Environmental Protection and the Israeli Water Authority.

“Desalination plants can be highly polluting due to the discharge of brine, which contains high levels of contaminants such as nitrates, phosphorous, heavy metals and residual chemicals used in the desalination process. These pollutants can severely impact marine ecosystems, harming aquatic life and potentially contaminating human water supplies used for drinking and agriculture. The high concentration of these pollutants can disrupt the balance of the marine environment, leading to long-term ecological damage,” Lev explains.

The impact of seaweed

The company still focuses on growing Ulva and Gracilaria.

“These species are particularly effective at absorbing nitrates, phosphorous, and heavy metals from seawater due to their high growth rates and robust nature. Additionally, they thrive in the controlled conditions of our land-based systems, ensuring consistent and effective pollutant absorption,” Lev explains.

According to the CEO, 1 tonne of dried Ulva can absorb 1.2 – 1.5 tonnes of CO2, 30-40 kg of nitrogen, 2-3 kg of phosphorous 0.1 to 0.5 g of lead, 0.5 to 1 g of mercury, 1-5 g of arsenic, 0.5 to 3 g of cadmium and 20-40 g of iron.

“It can also improve the overall efficiency of conventional chemical and physical filtration systems,” she adds.

What’s more, Lev says that the system also has a dual purpose.

“It helps clients comply with environmental regulations while providing high-quality seaweed biomass. This can be used for various commercial applications, such as animal feed, organic fertilisers and raw materials for the cosmetics industry. This not only adds an additional revenue stream but also promotes a circular economy by turning waste into valuable products,” Lev explains.

According to Lev, they have received “overwhelmingly positive” feedback for their systems.

“Companies such as Mekorot have praised our system's effectiveness in meeting regulatory requirements and contributing to marine conservation,” she notes.

And these successes have put Seakura on the radar further afield too.

“We are targeting the Gulf countries, which account for 60 percent of the world's desalinated water production and 50 percent of global nitrate output,” notes Lev.

© Seakura

Looking ahead

Seakura is now planning to build and train its team, improve its technology and build markets for its future seaweed harvests – which could reach 10s if not 100s of thousands of tonnes a year.

In order to do so, Lev says that they are looking to raise around $2 million.

“Seakura has been funded through a private investment. Moving forward, we will seek additional funding to expand our operations globally, enhance our technological capabilities, and support new projects. We are exploring various funding avenues, including venture capital, government grants, and strategic industry partnerships,” Lev explains.

“Mekorot is now also considering further investment in Seakura to expand the project to a commercial scale in other desalination plants along the Mediterranean shoreline. Recently, we also won a governmental bid to clean pollutants from Ashdod Port, marking yet another significant environmental milestone,” she adds.

And, if all goes to plan, these steps should pave the way for significant expansion.

“In the next few years, Seakura plans to establish three large-scale seaweed farms in Israel and internationally. We plan to expand our market presence and increase commercial sales of our seaweed biomass. Our goal is to provide innovative bioremediation systems that help industries reduce their environmental impact while creating valuable products from waste. We are committed to ongoing research and development to continuously improve our technology and adapt to new environmental challenges,” Lev concludes.