What inspired you to pursue a career in aquaculture?

When I left high school, back in 1974, I wanted to work outdoors. My father designed fish farms and my uncle had a trout farm and this was an area that fascinated me, so I applied for a job at a farm / research station in Monsted in Denmark, where I worked for 3 years, producing around 100-150 tonnes of trout a year.

It was a very important time for me – it gave me an understanding of fish and gave me confidence when talking to farmers – and I’ve benefitted from this for my entire working life.

What drew you into academia?

I wanted to be a farmer, but didn’t have enough money to buy my own trout farm – they were very profitable at the time, so I decided to go study fisheries (there was no specific aquaculture course available at that time) at the University of Tromsø, in Norway. The course required at least 18 months’ practical experience from fisheries, so I met lots of like-minded people who had come from fish farms themselves.

What appealed to you specifically about the aquafeed sector?

Looking at the feeds, the quality of the feeds and the quality of the raw materials was the natural topic for me and I joined BioMar, after five years in Norway and five years in academia looking at fishmeal production. One of the first things I did was to instigate a commercial PhD looking into ways to make feed more efficient by increasing the quality of the ingredients and thereby reducing the discharge from farms.

We showed that despite the diets being more expensive they were beneficial to both the farmers and the environment, increasing profits and decreasing discharge – it was a win-win situation. It’s a premise that is still fundamental to BioMar.

How has the aquafeed sector changed?

When I first started farming we were feeding the trout wet feeds. Blocks of raw fish caught locally round the coast, such as sandeels, pout and small pelagics, arrived on the farm and we had to mince them at 4am. Sometimes they were fresh enough that you could have eaten them yourself, other times they were terrible and sometimes they were too bad to use – there was a risk that they could contain botulism, which we called ‘bankrupt disease’ as it could kill an entire pond.

© BioMar

After that the sector developed wet pellets, then dry pellets, but some places – particularly in Asia – still use wet diets. I remember them still seeing it when I lived in China. They are dirty, risky, polluting and inefficient but fish, generally, still grow fine on them.

Perhaps the biggest difference now is that we’re no longer dependent on any one raw material – back then it was all fishmeal and fish oil, but now we can draw on a huge range of ingredients, which is a necessity. While fishmeal is still a fantastic ingredient it’s a limiting factor due to its finite supply.

What have been the most surprising developments in the sector?

The change from relying purely on raw fish to the development of dry diets with very limited fish content is the biggest change. The other is probably the structure of the salmon industry: when I left Denmark for Norway in 1977 I’d have never guessed that small family-run salmon businesses would evolve to become global companies listed on the stock market. Equally I’d have been surprised to learn that BioMar would increase its feed annual feed production from 20,000 tonnes in 1987 to 1.3 million tonnes today.

What have been your proudest achievements?

Helping to change the sector’s approach to diets based on increased performance and reduced environmental discharge and helping to establish BioMar in both Chile and China.

How do you see the aquaculture sector developing?

The developing world will have to make more efficient use of feed and water resources as well as improve their farming techniques.

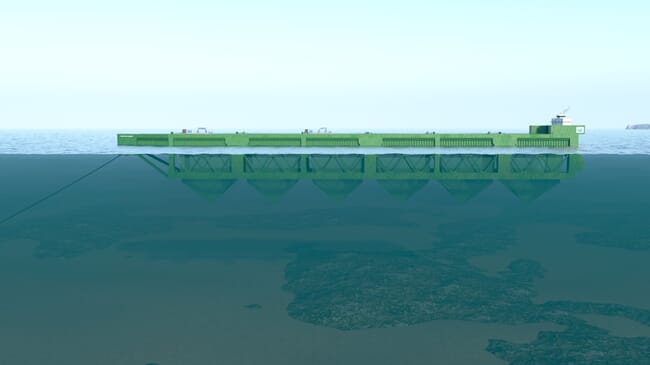

Meanwhile, in the West, real offshore farming will come soon – the companies and investments are already in place. At the same time the RAS sector will thrive – transporting fresh fish across the globe is a significant expense and it will make sense to farm salmon within key markets such as China and the US.

What do you see as the most promising of the current crop of emerging raw materials?

It’s worth remembering that aquaculture accounts for only 4 per cent of the compound feed market worldwide, so the pig and poultry sectors are likely to lead on the development of many raw materials.

However, we’re leading with many of the higher cost ingredients such as omega-3 oils produced by fermentation and there is scope for novel raw materials but it’s probably more important that we come up with new versions of existing ones – I believe there’s even scope to develop fishmeal and other marine ingredients in a more specific way.

More novel ingredients are no doubt interesting, but many are likely to remain niche products – there are 5 million tonnes of fishmeal used annually, but it’s going to take many years before insect meal, for example, can account for even a fraction of that figure. What’s more it’s going to come at a cost – after all the insects do themselves need to be fed.

What are the major obstacles the feed sector needs to overcome to allow the continued growth of global aquaculture?

We need to develop more specific ingredients for different species – we need to remember that salmon are only a small part of the sector.

We also need to make sure that all our raw materials are produced and processed in a sustainable way. Today, for example around 50 per cent of the fishmeal used in feeds meets IFFO responsibility standards and improvements need to be made, especially in Asia. The same could be said of other raw materials such as soy.

Do you have any regrets?

From a personal perspective I’d have liked to have lived for a while in Chile. It’s a fantastic country with nice people and I wanted to learn the language. I was poised to move there in 2001. We were due to take over a Chilean feed company. I’d rented out my house in Denmark and enrolled my children in a school in Puerto Montt, but the firm was sold to a competitor at the last minute.

What are your plans now?

I need to play more golf and spend more time with my grandchildren, but I’ll probably continue to work as a consultant for one or two days a week – for the next year or two anyway. It’s a great industry and it’s difficult to say goodbye – I’ve met a lot of good people in the business over the years.