© AMS

The concept has been developed by Shaun Gregory, a New Zealander who has been in the seafood sector for quarter of a century – both as a commercial fisherman and an oyster producer, based out of Whangaroa Harbour, north of the Bay of Islands.

Gregory began to investigate new ways to produce the shellfish, following his concerns over the conventional methods that he originally deployed. The main method for oyster production in the area was the “rack and stick” combination, but he noted that this system came with a number of drawbacks.

“It needs a huge footprint and isn’t great for the environment: you need to use heavily treated timber; if there is any major flooding, trees logs, and other debris can knock all the oysters off; and it’s also labour-intensive – I’d wake up with a sore back every morning from the heavy lifting which was required for constant de-clumping and grading of the oysters. It’s a huge cost for producing a real commodity product. And it’s also out of your control to get a nice-shaped oyster – they’re very rough and rugged,” he explains.

A catalyst for Gregory’s innovation came when a local company tried to develop a machine to half-shell oysters, without the need for the usual labour-intensive hand-shucking.

“They developed a very complex and expensive machine, but it still failed because oysters are all shapes and sizes and the location of the adductor muscle, which is the one you need to cut to remove the lid, varied,” he recalls.

The startup sold its first crop of "Qysters" in December 2022 © AMS

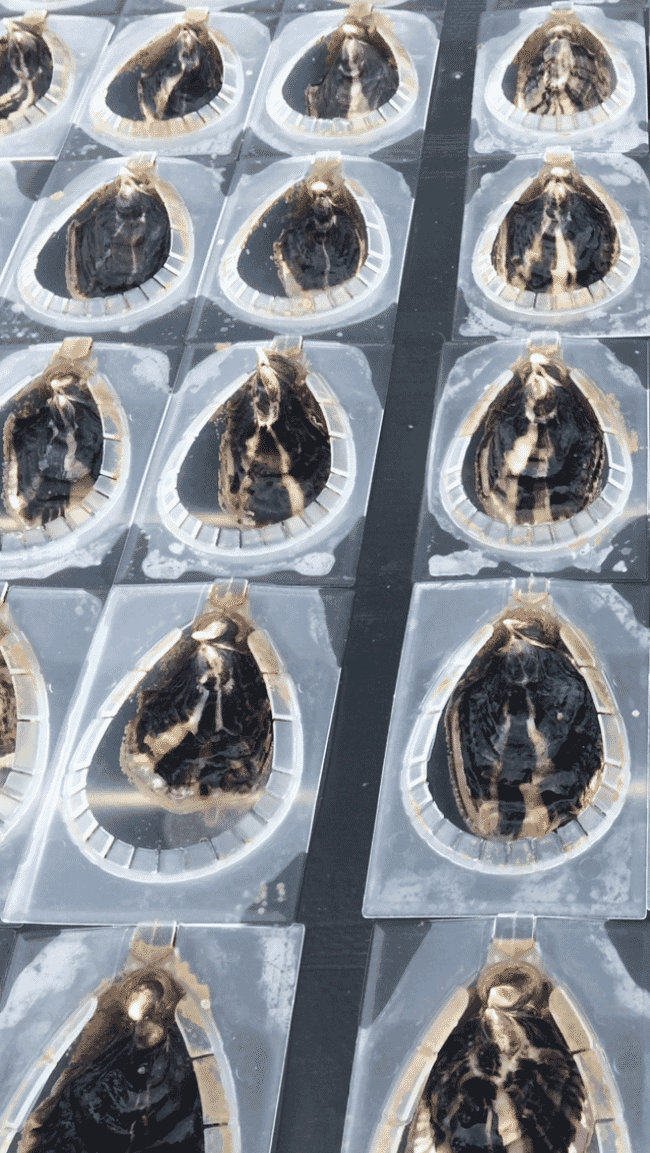

“It dawned on me that if you could make uniform oysters then it would lend itself to automation a hell of a lot easier. The original concept – to grow oysters in a mould – started from there. Another lightbulb moment was when I was grading some oysters in plastic trays, and I noticed that a mirror image of the lettering on the trays was clearly visible on the oyster shells that had attached themselves to the trays. I realised that it was possible to develop moulds that produced unique designs on the outside of the shells of the oysters,” he adds.

Thus, the concept of the Qyster (pronounced quoy-ster) – a deep, smooth-shelled oyster that has a Q clearly visible on its side – was born. Recently, many years since he first committed himself to the project, the first batch of Qysters to hit the commercial market have been met with a hugely positive reception from some of New Zealand’s top seafood chefs.

A rocky road

It has, Gregory admits, not always been an easy ride and in the intervening years – as well as building up the AMS Show Farm, at Opito Bay, in the Bay of Islands, to producing 27,000 dozen oysters a year – he’s been busy drawing up designs, applying for patents, bringing in investors and fine-tuning the design.

The end result is a system that is capable of growing 45 dozen oysters per dropper unit, equating to about 50 dozen per lineal metre of farm – well above the 10-15 dozen per metre that a conventional system can produce.

“It’s getting harder and harder to create new lease areas in harbours, so I looked into getting away from the single, linear design of conventional oyster farms. In cities they build skyscrapers, as they’re running out of space, and I thought I could so something similar, but going down. We now have five trays under each float,” he says.

The system allows farmers to increase production densities as well as create oysters of uniform shapes and sizes © AMS

Part of the development process has been ensuring that the design is not only viable but also economical and can be mass-produced at a reasonable cost.

Another has been the need to trial the technology across the full grow-out cycle of the oysters – as the molluscs take up to a year to reach market size.

“Every time you make a change you need to wait another year before you get the data you need,” he explains. “But the current model is robust, consistent, reliable and good to go.”

These can be stacked five trays deep, to increase the production capacity of a farmer's site © AMS

Most of the product handling previously done in factories can now be done at sea with the AMS Farming System, which drastically reduces the labour requirements. As each system drop is washed by a wash plant on a barge every 10 to 12 days, to keep the product free of biofouling, to maximise the available on-water up-time, the AMS system is best deployed in relatively sheltered waters, where it’s not exposed to continuous windspeeds above 25 knots. Although the washing process is not required in conventional oyster systems, farmers using the AMS Farming System face much less labour on balance.

“There’s no de-clumping, there’s no grading and the oysters are all perfect,” Gregory reflects.

Remarkably, despite the fact that the oysters are restrained in a system that has a lower rate of water exchange, as it houses more oysters, they actually grow more swiftly than conventionally produced oysters, with Pacific oysters grown in the moulds now reaching market size within 9 months on Gregory’s farm.

“Conventionally grown oysters come out of the water for about four hours every low tide, whereas ours feed 24/7 and only come out of the water each time they’re washed, which takes about 5 minutes," Gregory explains.

"The other reason is that they don’t have to be turned – a process that breaks the end frills and stunts the oyster – they can put all their energy into producing meats, rather than shells,” he adds.

This also means that there’s a large meat-to-shell ratio and Gregory says that his Qysters have the same meat content as conventionally grown oysters that are twice their length.

“This also brings advantages in terms of packing – having identical oysters makes life easier,” he adds.

However, Shaun Gregory aims to licence his patented oyster growing system internationally © AMS

Demand for Qysters

The company’s first Qysters were sold in December 2022 and, according to Gregory, they were met with a very positive response, fetching $30 per dozen – compared to an industry average of $18.

Qysters are 75 mm long, 40 mm wide and 30 mm deep, with a meat weight of around 26 grammes per shell. The depth, clean appearance and uniformity of the oysters have all been met with enthusiasm. But Gregory now aims to go one step further.

“In December or January, we will bring out a world-first, easy-opening oyster that will allow restaurants to open oysters in a few seconds, without any sharp blades or skillful staff. Some restaurants we sell to have two people continuously opening oysters. They’ll only need one person now, who only has to pull a lever,” he explains.

“We have also now patented the insertion of opening tabs into shellfish , so in the future, consumers just have to turn the tab and it will pop the oysters open on their plates,” he adds.

Gregory sees this easy-opening oyster as having the potential to be hugely disruptive – a hunch that’s based on a childhood experience.

“When I was about 12, my old man bought an orchard and was raving on about a new type of mandarin with no pips that was easy to peel. Back in those days they all had hundreds of pips and were real pricks to peel,” he recalls.

“He predicted that those growers who didn’t move on would be left behind and he was dead right – five years later they couldn’t even sell the traditional mandarins for pig tucker,” he adds.

It’s Gregory’s firm belief that “easy-peel oysters” will come to dominate the market within a number of years.

“Opening oysters is the real pain point in the industry,” he observes.

Critical mass

It’s clear that – many years since his Eureka moment – Gregory’s business is finally poised to emerge from stealth mode and take the shellfish sector by storm.

“Now that we’ve proved the sales side of it, we’re ready to go to market with our AMS Farming Systems,” he reflects.

In terms of a business plan, Gregory is looking to licence the Qyster-growing units internationally and AMS currently has patents in nine countries – including in New Zealand, Australia, USA, Canada, Japan, Singapore, China, Gulf of Mexico and the UK. Although he has done the hard work in terms of designing his system, he now needs to concentrate on growing the AMS business.

“There’s logistics, there’s costs, there’s establishing agreements with distributors, there’s setting up the tooling in other countries – those are the challenges we face over the next 12 months,” he notes.

In order to help achieve the next phase, Gregory is looking to bring in new shareholders, but mainly on the condition that they bring valuable experience – of the seafood sector, international markets, or other experience relevance to the development of the company – rather than just funding.

Gregory's first commercial batch of Qysters sold at a premium © AMS

Looking ahead

Now that the company is up-and-running Gregory is looking forward to both growing and diversifying.

“I’d like to see us move into developing similar systems for different varieties of high-end bivalve shellfish, like scallops, and our patents cover all shellfish. We’ve put a lot of R&D into the farming side, now a lot of our focus will be on the factory side…. focusing on the automation of processing and packaging Qysters,” he explains.

He also plans to have a new, unique way to ensure that each Qyster is traceable, right up to the farm and the row it was grown on.

Meanwhile Gregory is looking to build his own business experience, his team and his network – something he is currently working on through taking part in a new aquaculture innovation launchpad run by NZTE and Hatch Innovation Services.

© AMS

“We’re more of a tech company than an oyster company and we will continue to focus on R&D so we can continuously develop. I’ll be using the launchpad to refine my business plan and model, to meet people who can see the potential of incorporating the AMS farming system into their business, and to get contacts who can help us to grow internationally,” he explains.

As part of the programme Gregory will be visiting AquaNor – one of the world’s largest aquaculture fairs – which takes place in Trondheim on 21-24 August.

“We’re already starting to get good contacts from the Hatch launchpad. There are so many hurdles in the way, which vary from country to country, so if you meet people who can help you overcome those hurdles more quickly it really helps,” he concludes.

Get in touch

To learn more about the AMS Farming System visit https://qyster.co.nz, and to arrange a meeting with Shaun Gregory at AquaNor drop him an email via Shaun@aquamouldsystems.com